Click on different countries and cities to explore Korean War memorials around the world!

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> He's the leader or the president of his association, and he's a retired veteran.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> "And I am a veteran from [INAUDIBLE]."

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> This association started in 1984 for the [INAUDIBLE] and Korean War Veterans.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> This association started [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] the small room. In 2004, the government allowed this building to give ... Gave this building for the veterans.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> And the current population of this building is 2,005 people.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> And 200 people of these people are from the Korean War.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> The youngest of these Korean veterans, he is 86 years old, and about 70 percent of these people can't even walk and are currently staying here.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> This room is made for the Korean Veterans for them to meet once every week on Thursday to spend their time and meet with each other.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> And from the objects they gave us ...

>> You saved. They remember you too.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> He's really happy, and he's hoping that South Korea stays strong.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> He's telling you that ...

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> ... when he went back to Korea, he realized the kids these days are taller and bigger [INAUDIBLE].

>> Aw, don't cry.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> Oh, thank you. Do you remember me from 2009 when you visited Korea?

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> He went to Korea in 2012.

>> Oh, '12.

>> He didn't go in 2009.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> When they were coming back from Korea, they went really fast.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> When the plane landed really hard on the ground, all five of us lost our balance really hard, and it did to us something that [INAUDIBLE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> People who see us might look at his age, but he's still [INAUDIBLE].

>> Oh, thank you.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> Thank you.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> Okay.

>> You saved. They remember you too.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> He's really happy, and he's hoping that South Korea stays strong.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> He's telling you that ...

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> ... when he went back to Korea, he realized the kids these days are taller and bigger [INAUDIBLE].

>> Aw, don't cry.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> Oh, thank you. Do you remember me from 2009 when you visited Korea?

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> He went to Korea in 2012.

>> Oh, '12.

>> He didn't go in 2009.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> When they were coming back from Korea, they went really fast.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> When the plane landed really hard on the ground, all five of us lost our balance really hard, and it did to us something that [INAUDIBLE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> People who see us might look at his age, but he's still [INAUDIBLE].

>> Oh, thank you.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> Thank you.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> Okay.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> We were invited in 2010 to go to Korea with my wife.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> When I was injured back in the war, I took an ambulance that went past the Han River.

>> One bridge [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> There was only one bridge that was about to be collapsed.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> But when I went back in 2010, I saw there were 29 bridges on the river, and I was really impressed.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> He's saying all the Korean people are really polite and hardworking.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> One day, they took us to a village.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> It was 75 kilometers away from Seoul.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> It represented Korea 100 years ago. They made a village to present that old time.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> It was sort of a museum where they created a scenario of Korea 100 years ago where kids would go to learn about Korean history.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> When I went there, I saw kids sit down in the [INAUDIBLE] and the teachers would explain them about the history of Korea.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> And after the teacher told the kids about the stories, the kids started running towards us, and they started hugging us and kissing our hand.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> There was one really handsome kid. I think he was around 13 years old.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> He hugged me and kissed my hand.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> And he looked up to me and said, "Atatürk."

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> And when I looked, the teacher was waving. She was waving her hand.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> The teacher basically told them about the Turkish soldiers, how they lived thousands of miles away, but they came to our country and fought for us, and their leader was Atatürk, and she told this, and he cried.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> I went to his mausoleum in Ankara, yes.

>> When I was in Korea, the sergeant told me to write pages [INAUDIBLE] for you, and I [INAUDIBLE] restraining regiment, and we had the signal hut which was this one here originally built by the Canadians on hill 355 which I think [INAUDIBLE] are in there. Oh, just jumping. That's when I first arrived in Korea all smart and signal office, and I first arrived there. You see it says, ,"Signal Office." Very naive, not knowing what to do, but, you know, learned very quickly. That's after about 3 months in Korea. See the difference between the smartness one and on after being in the frontline? Being in the frontline, do you see the difference in my dress? That's that. That's during the winter. We was just stuck in the ice. I figured [INAUDIBLE] was but we couldn't move, but we eventually got pulled out by a tank. This here, very difficult to see, very difficult to see, but these two photographs here, the helicopter is coming in to pick up the wounded, [INAUDIBLE] to I think it was the American mesh which we had to call in with coat signs and everything. That's me showing off with American carbine which I swapped with an American which must have frightened the Chinese North Koreans, must not it if they saw me there. This here is a Christmas card left on the barbed wire by the North Koreans and/or Chinese with toothpaste, razor blades, etc, etc, and the wording is very, very, very good because it's aimed in the English colloquial language, so once you start reading it, you understand what it's saying about American Imperialist, things like that. I'm not sure many more photographs that I think was taken in rest somewhere, you see. This is a story run by the Daily Mail in December the 27th, 2013 by a man called Tony Randal about the Korean War. "Bloodbath that nearly drowned the world," and he gives the political aspect of what communism was going to do if it really ran the world. So what I did, I wrapped this in paper, and I wrote this story. I wrote this little thing here which you may want to ... Should I read it?

>> Yes.

>> I was there. Please keep this for my grandsons, great-grandsons and all the descendants. This is what it looked like, and on many occasions, much worse. I shared a hoochie, a dugout, with other young servicemen, Brian who was 20 years old, a bit older than me. I was 19, and [INAUDIBLE] lived with his gran. One morning, 1952, he said, "I do not want to wake you up because the rats are eating their bars of chocolate, sandbags, next to your head, and I thought if you moved, it would jump on you." At 12:00 that day, he was dead. That's war, and that's what I put, and so I hope that descendants and descendants, descendants, remember. It really was the last real conventional war that there was, not that that made it any good or any better, but that's that. So this can be found in the Daily Mail archives on December the 27th, 2013 by Tony Randal, a historian which reminds people that war never achieves anything. It just takes the lives of young men, the cream of all societies whatever nation they're in.

>> [INAUDIBLE]

>> That's it. I [INAUDIBLE] national servicemen, but I do say they're just as scared as we are and didn't want to be there any more than we did. I'm glad we could help. Signing off. Young boy.

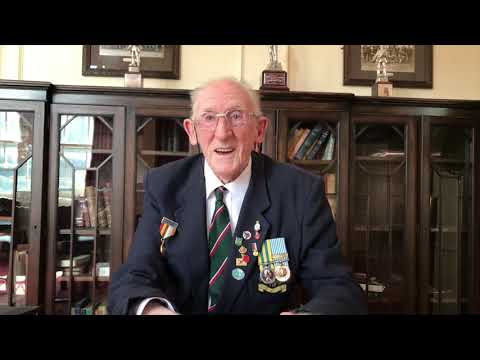

>> My name is George Reed. I'm a member of the British Korean War Veterans Association. I'm the secretary of the Hertfordshire branch. I went out to Korea with the war engineers, and it's a great shock. It was entirely different than being back in England, and I got posted up by the Imjin River [INAUDIBLE] engineer squadron, and we generally worked to do the reservicing roads and Korean work. The war had just finished when I had got out there, so the fighting had stopped. There was still plenty to do. I eventually became the squadron welder, and I built a 47-foot observation tower practically by myself, and then I got put into the intelligence section, was entirely different type of work altogether. Quite fun, I've done a few explosive jobs and blowing up. I've done some welding on the Teal Bridge, which would run ... crosses over the Imjin River. This was preparing for explosives in case the war started up again. I had plenty of work to do. I was very interested in most of it. I don't regret going out there. It was quite a different type of a culture, and, well, I bet we were. There was hardly any people at all because all the villages had been either destroyed, or they'd been moved back out of the danger area.

>> Did you know some of the comrades or people that went, fought in the British Armed Forces that fought but that didn't make it back? Did you know anyone?

>> Who fall down there?

>> Mm-hmm.

>> Yes. I was in the [INAUDIBLE] army before joining the regular army [INAUDIBLE] and there quite a few regular [INAUDIBLE] who fought out in the Korean War. They were very ... Was it posttraumatic stress? Two or three of them suffered very badly from that and what went on, but it wasn't recognized back in those days as such, so they were never treated, and they quite introverted to theirself. It affected them quite badly.

>> You were so young. How old were you?

>> How old was I when I went out? I was 21 when I went out to Korea. Being an engineer, it's a bit of employment. I was serving an apprenticeship for 5 years. I was deferred for joining the Army or doing national service for 2 years.

>> Explain that a little bit about the national service because it's a little different from other countries where everybody volunteered.

>> National service was 2 years, member, conscripted and then medical, and if they passed, they were sent out to different regiments, but I planned on being a military mind at that time. I signed on as a regular soldier, so it was all with national service. We don't have training with the national service, and it was all posted out with the national service with the different units around the world. I can't view it from a national service point of view because I wasn't a national serviceman.

>> But you served with them.

>> Yeah. Most of them were national service in those days.

>> How ... What do you think the proportion was?

>> In those days, it's over about 60 percent national serviceman in the British Army. I should say, not knowing these figures, but yeah. Looking back now, and what I've heard, I've met a few Korean people. I was in France 2 years ago, and in our hotel was a young Korean lady, and she thanked me for what we'd done out in Korea when we was fighting, so it ... quite lovely people there, very lovely people. Well, I think so. Yes, and I hope to be going out there in April of this year on a first visit for 62 years, all going well, hope to be there to see how the culture has changed, how the building changed because when I was there, Seoul was in a pretty bad state also the Gyeongbok Palace, which I remember visiting it if that's still there, but yes. I understand it's entirely different now, so going to compare the two different eras.

>> Well, I hope you enjoy the visit. I think you will.

>> Yeah, yeah.

>> I thank you.

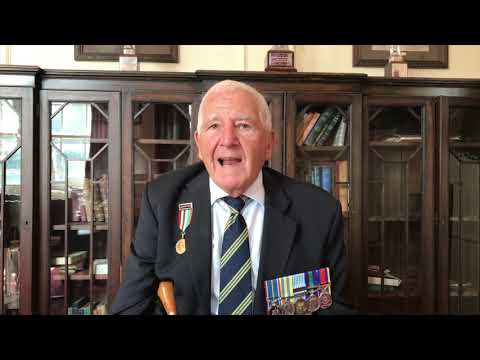

>> Hello. My name is Roy Painter. I'm a trustee of the British Korean War Veterans Association, and I served some time in Korea from 1952 to 1953 as a national serviceman. Most of the time, boring, some exciting, some of it very scary, but that was the way of the world then in 1952. I didn't think much of it when I came home, but now it means an awful lot to me when I see what the Korean people have done and very pleased and proud that it part of this regeneration of Korea, and I realized this. Now as you get older, you appreciate just how important it was that the part we played in the British Commonwealth Division and my colleagues. Forty-some of us never came back, like my friend Brian. He was only 20, who life dealt a bad deal, an orphan, in any case, was living with his grandmother, I'm afraid didn't come back and is still in the Korean cemetery. I suppose that's all part of war, and the bad things that happen, but the good things is that Korea is on its feet. The people are very generous to us, the Korean people, and it means so much to me that they have done this, and in some tiny cog in a bigger cog in a bigger cog, I played some part in it. Some things happened to me there. I went on a rest and recuperation leave, and I brought back a 1 yen. What that's worth now, I don't know. I visited a Buddhist temple while I was there, which, again, enlightened me. This is a couple of colleagues I had. That was me there, looking about 10 years old, but it was 1952, and we were all young and didn't care very much, some more photographs. The entertainers came out. That was a lady called Carole Carr, who was a very famous singing star in the '50s, and there she was. This here is my first introduction of working in the career, the signal office before I got sent up with the others and where it all happened, and this here is the ship I got sent home in, not much bigger than a Thames barge, actually, but there we are, but I've got some other things I could tell you if you want. Oh, this here, I was very pleased that I got invited back to Korea in November '14, and the generosity of the Korean people and everybody. The Ministry of Patriots awarded me the peace medal, and this parchment here, which I think I'm very proud of, which I hope in generations to come, my grandchildren, great-grandchildren, great-grandchildren will look and feel as proud as I am when I received this. Well, also, they fished out these Christmas cards from the American people. I don't think she realized it was going to an English person, but, nevertheless, it was a delightful, delightful Christmas card from a grandmother in America wishing us all the best and that someone was thinking of us, which I thought was very, very generous of them. I did reply to the lady, and I hope she treasures my reply as much as I treasure this Christmas card. Oh, and there's lots I could tell you, could go on forever, really. At 60-odd, the UN decided to declare war in Korea. Now most of the people in England didn't even know where Korea was. You got to remember the time. We were still on rationing. We were the poorest country in Europe still. We'd been bombed out. My father had been in the army for 5 years. My house had been bombed. We were sleeping downstairs in two rooms, sleeping on mattresses on the floor. By 1945, that was then. I left school in 1948, and, of course, in 1951, like other young men, I had to do 2 years' National Service, which I was called up. I went to various parts of the United Kingdom until some time in I think it was March when I was in there, when I was called into the colonel's office and told, "You're off to Korea." Korea was some Asian, some ... The other side of the world, which of course it was. Anyway, pack your gear, go home on leave for 2 weeks, which I did. Wound up in Liverpool on a boat, had 6 weeks of very pleasant trip to Busan, saw parts of the world I never would have seen. We slept on-deck, and we got to Busan, where we was introduced to Korea. Spent 1 week there getting acclimatized, and then we boarded a train to go to Seoul, and it took us 37 hours, stopping, starting. We got to Seoul, out of Seoul. We got on Canadian tracks. We then went another 5 hours, and suddenly the reality of it hit me. I could hear guns firing. I could hear bangs. Oh, dear, this is the reality, but we all made silly jokes and said silly things, and I got to where I had to go in the Commonwealth Division, was fed, watered, and we all had to swim in a local stream, got all the dust off us, and then I was sent to the signal office where I was introduced to the workings of what the army life was really about, and strangely enough, within 2 days, the first message I received was of a schoolmate who sat next to me at school had been wounded, shrapnel wounds, head, severity, severe. How small a world is it? Then the next 6 weeks, I got acclimatized to everything and became what I suppose was a working soldier. Sergeant then come down, said, "Okay, Painter, we're going to cook your goose. You're going up to the Aussies now," and then in a jeep over the Imjin River, carried on. The gunfire got louder and louder and louder, and suddenly reality started dawning. Oh, dear, this is what it's all about, and I went until I was attached to the first World Straits Arrangement, and I was introduced to the colonel, and the sergeant, he was a grisly old Aussie who had been in the army for years, said, "This is your new English operator, a pommy," he said because they called English pommies. This is your new pommy operator. Wise operator said, "If you don't mind me saying so, sir," he said, "I think the poms is still sending us kids. They're still shipping young one on their mother's tit. They all look kids." Anyway, it was a start of a 3-or-4-month acclimatization. I learned very quickly to tell the difference between outgoing shells and incoming shells, but it wasn't that bad because everyone else was used to it. We did guard duties, and I was always impressed by the clarity of the sky at night, especially in the winter. It was so clear and clean-cut, and I looked at the stars, and I thought, "Wow," and I should try and work out in my head how far away it was to go home, 6,000 miles. If I walked it, could I walk through Mongolia? But then a routine settled down. I was a wireless operator, and you spent 6 hours on-duty, 6 hours off, but mostly it was fairly easy until sometimes, things got slightly naughty, and mortar bombs started landed on us, but it only lasted a few minutes, but it still used to make you scared, and people said they wasn't scared are telling fibs because everyone gets scared, but then you did guard duties, and you'd look at a bush, and you'd think, "Is that bush moving? Is it someone really there?" And I said ... I think peoples turn to religion. We all make false promises, and the shells we'd land on said, "Please, god, don't let them come any nearer. I will go to church," knowing I wouldn't, but time passed, and then I got attached to the Americans, and that was a lot of fun. They had food I'd never seen before, chocolates and steak and ham and eggs for breakfast. It was unbelievable because you have to remember that England was still on rationing. We were still on starvation rationing in England, but sweets, and time went by, and suddenly I'd been there almost a year, and I went on one leave in Tokyo, the rest and recuperation leave, which was fun, 5 days, lots of boozing and things like that, but that's what young soldiers do. Isn't it? And I came back, and where I could ... It did change my life. I remember looking a the Koreans, and I can remember them opening up a tin of bacon. It was a big tin. It was bacon inside. They took it out, and I remember saying to my mates, "Korea will never go back to being peasants again. They've moved 400 years in 2 years. They've seen now what the rest of the world has got," and I can remember these two young Korean guys taking the bacon out, and I thought, "They're eating the same as us, wearing the same clothes." Of them, those that were lucky enough to be with the Americans got all the goodies. They don't want to go back to eating rice and fish. Korea is going to change. They're going to want what they're ... and quite rightly so. It was a few moments. We never saw many civilians, but I can remember one was a Korean peasant lady who was way down in line, and she had a baby strapped to her back, a little boy, and as most soldiers do, I wasn't mean. I gave him two bars of chocolate, and the gratitude of the Korean mother was so immense that even at 19, I was moved that for two bars of chocolate, life should not be like this. People shouldn't be treated like this, and how could the north come down and raze these villages to the ground and kill people? I suppose it was part of my growing-up process. Wasn't it? This was wrong. This was wrong, and was I pleased I was taking part of that, of helping? And eventually time came, time to come home, and I did, and I must confess. I put it out of my mind, Korea. I put it out of my mind, but occasionally on my own I would think about it. I'd think about it. It never ... People say they have, what, post-traumatic ... I don't think it ... I had a few sleepless nights. I would wake up, and I wanted one experience, this, okay? When I went to an army camp in England some years ago, and they'd recreated the 1914 war with sandbags and shells, and I went through, and the shells started whistling, and my stomach did turn over. My tummy turned to water, and it brought back memories, but I soon got over it, like most people decided. I'm not sure about post-traumatic stress, but if people suffer from it, then I feel very sorry for them, but then I got a phone call in the ... oh, dear, from a man called Rod Larby. He said, "I know if you don't like to see your man's grave, Brian Clackett." And of course, the memories come flooding back. I said, "No," and Brian was only 20, and life dealt him a bum deal, which I think I said earlier. He was only 20, and he was an orphan. By 12 o'clock, he was dead, and so I became involved in the British Korean War Veterans Association, so I'm going to meet my old pals, told lots of lies to each other, didn't we? As we always did, but they were older. You remember some of that. Do you remember him? Do you remember him? Until eventually I went back on a revisit in November 2014, and I'm so pleased I did. The change in Korea is just phenomenal. They're the 10th largest economy in the world now, and if winning this war in South Korea could do this, why can't North Korea? Why can't other nations use this industry and do good things? Anyway, on the revisit, they arranged for me to see Brian's grave, and I must confess. I did get emotional in this time because it shouldn't happen to a 20-year-old, but I saw his grave. The graveyard is kept absolutely immaculate. The Korean people are ever-thankful. I don't mean grateful but thankful, which is nice, and isn't it a pity that the north is still the same as it was? Isn't that a shame? Isn't it? You'd think that ... words fail, especially with this lunatic in charge keeps his people in servitude and slavery, and we can only hope that all the people that died didn't die in vain, and that Korea becomes one nation. It's leapt from 1600 to the year now 2000. I can't believe it can carry on as it carries on now, and all these people died for nothing. You know? Fifty-six thousand Americans, over 1,000 Brits died and 1,000 were taken prisoner, and let's hope that we can all learn that man's inhumanity to man can't go on, so now in my 80s, am I pleased I did it? Oh, absolutely, I'm pleased I contributed in some way. I made friends and comrades I would never have made. I experienced something I would never have experienced before. I was privileged, just privileged to take part in some tiny call freeing South Korea from the yokes of North Korea, and so, really, I can go to my grave saying, "Well, I did contribute something to the world, albeit forced to do it but pleased to do it," and let's just hope that in my lifetime, Korea can unite. One thing I did forget was on Christmas 1952 at midnight, all guns stopped firing, which just very quickly became an eerie quietness. It was like, but on Christmas morning, strange enough on the wire before the minefields, the Chinese or North Koreans had left Christmas cards and little presents like toothpaste, razor blades and other things, and the Christmas cards were specifically worded for English. Hello, lads, merry Christmas. I hope you're enjoying some presents, but do you really want to fight for the American imperialists? While you're here, they're taking your girls and wives back home, and you're fighting a useless war. Do you really want to fight this war? What they didn't realize, it was counterproductive, of course, because we all laughed. It didn't really have any effect on us at all. We just laughed because we could see through this propaganda. It didn't really affect us. I will look for this card again because a picture is worth 1,000 words, so I hope I can find it and some other, but, of course, I wasn't expecting this, so I really don't know where I've put it, but I really must try and put this all in order for future generations.

>> [INAUDIBLE].

>> Because it didn't go like that. It wasn't on the spring. Each time, we had to wrap it round and ...

>> And because it was crystallized, you had to break it up.

>> Yeah, trying to start it, but now you've got more springs, haven't you?

>> Oh, yeah.

>> This time you had to keep wrapping it around, pull it, pull it again.

>> Until ...

>> Oh, and it wouldn't start, and I could hear the guns firing, and I thought ... and I could hear the radio going because we had batteries, and I couldn't answer it ..

>> Because you're trying to answer back.

>> But I can't right now. There's no power.

>> So you had to keep doing ...

>> No power, and you couldn't have the generator inside to keep warm because the fumes would kill you, wouldn't they, of the generator?

>> Yeah.

>> So you have to have the generator outside, and, oh, my fingers were cold, and it was so cold, and it wouldn't start. I thought, "Oh, I'm in such serious trouble here. I'm in serious trouble." Vroom. All of a sudden, it was all [INAUDIBLE].

>> And then ...

>> Then it went. Oh, and I got in the air. Hello, whatever it was, Newcastle One. Hey, you read me? Over. Read you fives and clear, duh, duh, duh. It was fine. But if you look, that was the night of the Battle of the Hook. Think it was October, was it, '53? You got it there?

>> No, I'm recording you.

>> Oh. And it was Battle of the Hook. If you put it on there, Battle of the Hook, you'll see it.

>> Yeah, yeah, I will.

>> And that was ... And the journey started. But I remember the night was so crystal ... You know when you get that clear air and all those millions and millions of stars because it was so clear, the air, and I could hear all the mortar bombs landing on the Hook and things like that, and I didn't realize what a pounding they was getting, and that was it. If you look it up on there, Battle of the Hook ...

>> We will.

>> Oh, by the way, since you were in the National Service, you did get paid, right?

>> Oh, yeah. When I first went there, I got a pound a week.

>> Oh.

>> One pounds, but the average wage was about ...

>> Relevant to the day, I suppose.

>> The average wage was about 3 pounds.

>> Oh.

>> And I got paid a pound. Then it went up to 2 pounds, I think. By the time I come out of the army, I was what they called a five-star soldier.

>> Oh.

>> Five stars. I didn't have to pass any exams, and I was getting 3 pounds, 10 shillings, and for fighting in Korea, I got 82 pounds bounty, 82 pounds bounty, which was ... In '53, it was a lot of money.

>> What is that now?

>> What?

>> What is ...

>> Eighty-two pounds bounty in ... The average wage was, say, four quid.

>> Yeah.

>> So it was what?

>> So the average ...

>> Four into 80 would be 20 times, wouldn't it? So 20 times ... Say the average range is 300 now. Twenty times 300 would be 6,000 pounds. No, it wasn't 6,000 pounds. It would be worth, I don't know, couple of thousand quid now.

>> Yeah, today.

>> It was called a bounty. I didn't get it until I went home.

>> So it's 1,000 times what ...

>> Yeah, yeah, yeah.

>> It's 1,000 times better than ...

>> For, yeah, bounty. It was bounty, yeah.

>> So you were adding 1 pound ...

>> But remember, I never spent any money for a year.

>> Yeah, because you would have nowhere to spend it.

>> It's like being in that field. You can have 10 million pounds, but you can't buy anything if there's nothing to buy, can you?

>> No, so you saved it.

>> I got free cigarettes, and I didn't smoke.

>> So you saved ...

>> You got free cigarettes, 15 cigarettes a week in tins, and then you got a menu called C-rations. [INAUDIBLE] C-rations, you got bone chicken ...

>> Yeah.

>> ... toilet paper, matches, four cigarettes.

>> What did you do with the cigarettes you were given? You were giving them away?

>> He traded. He bartered.

>> You bartered?

>> No, we played cards with it.

>> Oh, were betting.

>> I'll raise you 1,000 cigarettes.

>> Oh.

>> But also we had a Korean guy with us when we were down, and he would do our washing, and you'd give him ...

>> Some cigarettes for the washing.

>> You would give him 300 cigarettes, and he would go to Seoul and sell the cigarettes. He would sell the cigarettes.

>> It was bartering for service.

>> Yeah, yeah. He was ... And he would smash it against the rocks, get the stuff clean, but of course, that was back down the line. When you was in the line, you'd get ...

>> Take it ...

>> So ... But I didn't think it ... Looking back now, I go ... I didn't view it as being bad.

>> It wasn't.

>> I didn't view it ... I viewed it ... That was ... Like Bill said today, I viewed it ...

>> Mm-hmm. As part of ...

>> That's how it was.

>> That was how it was. We ... That was it. I didn't view it, "Oh, look at what they're doing to me," because everyone else ...

>> Yeah, everyone else was doing it.

>> Everyone else was doing it.

>> Yeah.

>> And it was lots of fun there as well. We'd ...

>> You're in it together, so there's no one ...

>> I remember this American. We were swapping, and a STEN gun, British STEN gun, which was terrible, and it cost the equivalent of $1 maybe, and so I fired his carbine, and he fired it. He went, "Man, that's the sweetest dollar's worth I've ever seen." So we swapped guns. I took his carbine, and he had my STEN gun. Carbine was much better.

>> Yeah.

>> And so I didn't view it as, "Oh, terrible." It wasn't terrible ...

>> It wasn't at the time.

>> ... because it's ....

>> Relevant.

>> It was relevant at the time. We all ... We laughed. You joked, and you made jokes, and you read books and read, read an awful lot.

>> And it was an adventure.

>> Yeah, right, and I said ... We had a radio, of course. We had the radio up. We could tune into the radio, and we used to tune into the radio when it was the March of Dimes. Give a dime today for a Korean orphanage.

>> What was your favorite song again?

>> Oh, there's lots of [INAUDIBLE].

>> Really? Really there was ...

>> Favorite songs at the time?

>> ... March of Dimes for Korean orphans, really?

>> Yeah. They said, "This is the March of Dimes. Give a dime today for a Korean orphanage." They're the March of Dimes, so you know it's ...

>> In the British radio stations?

>> No, we picked up the American radio because I was on the radio.

>> The American.

>> We never had a British radio station. Only the Americans had their own radio station. This is ... Songs was ... [Lyrics] Way back home, we lie. We used to laugh at the Americans being all sentimental. We weren't, but they was ... It was like going camping with them maybe for a year. Imagine going camping with that [INAUDIBLE].

>> Shooting down.

>> Yeah, no. Imagine going camping for a year and ...

>> Yeah, an expedition, sort of adventure.

>> Yeah, but trouble is sometimes you run out of food because no food was coming up.

>> So you had to ration.

>> You had food, and you had these C-rations most of the time, which is a pack like that like you could buy at the supermarket, bit of chicken or meat wrapped in almost ... It was toilet paper, cigarettes, matches, maybe a piece of cake or something like that. My mom sent me a parcel, a big parcel at Christmas. On Christmas '52, we had the highest ranking general in [INAUDIBLE] come and see us because we was the most forward of the British soldiers in Korea, and he come up to see us, and he come up to see us, and I had this big parcel. So I go, "Cup of tea, sir?" "Yes, I'll join you lads," and his gloves were rolled back, and he had this camel-hair overcoat on. His hat, boots, brown boots glistening. He really looked smart, he did, and, "How are you finding it, lads? Getting tougher?" "All right, sir." "Well, chin up."

>> What did you guys think of MacArthur?

>> He was gone by the time, I think, I got there, wasn't he, MacArthur? Was he?

>> He was fight ...

>> He might have just been there. I think ... MacArthur, General MacArthur?

>> Mm-hm.

>> No, when I got there, he was general ...

>> Eisenhower?

>> No, no, no, no, general ... No, the general took over from him. There was another general. I have to think about that because MacArthur wanted to drop the atom bomb, didn't he?

>> Mm-hm.

>> And they took him away. Then they took him. There was another general. I forget his ... There was a man they called Iron Guts somebody.

>> That was his nickname, Iron Guts?

>> Yeah, another general, Iron Guts someone. I'm trying to think who the other American general was. I forget. There was another general, American who took over.

>> Nevertheless, what did you think of MacArthur?

>> I didn't give it a thought, quite honestly, although you've got to remember, he pulled a master stroke, didn't he, the Inchon landings. He pulled a master stroke. Here is Korea, and we were down here, and there was the Chinese. What he did, he landed all the troops there In Inchon and cut Korea in half so they was all trapped.

>> Oh, yeah.

>> It was a master stroke really. He really landed, and it had a 15-foot tide. This place called Inchon had a 15-foot tide, so they had to time it ...

>> Perfectly.

>> And that was British marines in there at the time, but it was tragic. When they got there, they took it without almost a shot being fired, but nevertheless, [INAUDIBLE] landed so much, and they just cut it in half. So it was a master stroke. What was it, 1951, was it? Late '51, I think it was.

>> '50.

>> General, general, but there was ... As I'm talking, I'm remembering things that I ...

>> September.

>> September of 1950, was it?

>> Mm-hm.

>> I wasn't there then.

>> You were '53, weren't you?

>> No, I went there '52 because MacArthur sat ... because he really did that to Truman, didn't he? Truman had to go and see him rather than him go and see Truman, and he fired him, but he got a hero's welcome, didn't he? Ticker tape in New York, and do you know he had not been back to America for something like 30 years?

>> Mm-hmm.

>> He had not lived in America for 30-odd years. He had been in ... And you know that photograph of him walking up the beach? I've read the story. He walked up the beach. There's a famous picture of him with a cob pipe in his mouth walking up the beach. When he left Manila, he said, "I shall return," okay? And they had a picture of him walking up the beach, but that was a mistake. The boat wouldn't land, so he had to get in the water, and he cursed and shouted, and the guy took a photograph. Of course, he ... And it's really ... He cursed and shouted. He had to walk up the sea, but of course it became a famous photograph like he's walking up the beach, isn't it?

>> Like a holiday brochure.

>> Well, yeah, like he's returning, walking up the beach all ... And yet he was actually fuming. He was actually fuming, but then it took ... But he hadn't been back to America for 30 years, MacArthur when the Japanese took Manila and all that, and he sailed southeast. He never went back to America so ... He was going to run for President, wasn't he? He thought he was going to be President, MacArthur.

>> When he went back?

>> The reason they sacked him, he wanted to drop the atom bomb on North Korea. Had he done so, it would've been ...

>> Catastrophic.

>> Would've been catastrophic. Russia would've done it, but it was ... So as you talk, you remember things, don't you?

>> Mm-hm. You have to all write it down and finish your essay. I'm urging him to finish his essay.

>> I've got another piece I want to fit in.

>> [INAUDIBLE] bar cream.

>> Let's get this week over, and I think I'll cut everything else out and just do ...

>> The key to it is to ...

>> ... the story of my life.

>> ... write it down when you remember it, right?

>> Yeah.

>> Well, sometimes when I'm writing, it comes.

>> That's true, too.

>> Going back.

>> The story ...

>> That, of course, is when I was boy. When I was 14, I was boy. I went in the Navy, so that's me ... That's GMS Ganges, nothing to do with Korea, me hat.

>> [INAUDIBLE].

>> Wow, it is.

>> Yeah, well, [INAUDIBLE].

>> Their badges is the royal signate.

>> No, it's not.

>> Oh, sorry.

>> Wrong signal, wash your mouth out. It's the REME. That's the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

>> Hello.

>> And that's the badge there. Right. Now he's Royal Signals.

>> Royal Signals, and what does that mean?

>> Communications.

>> Oh, so your badges all indicate what you ...

>> Yeah. Mine was repairs ...

>> Hello?

>> ... maintenance of old vehicles and equipment, that's REME, Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

>> How about his?

>> He was Royal Engineer, slightly different.

>> What is that?

>> Pardon?

>> What your regiment badge is?

>> Your badge.

>> He's Royal Engineers, Eamus.

>> Yeah.

>> What does that signify?

>> Paratrooper.

>> Oh.

>> RAF Memorial.

>> I was in the 27th Brigade. That's all of them. That's the Canadians, Australians. That's the New Zealanders, Canadians, and that's two badges there, and that's a one-eyed ... That's a good-luck charm, that is.

>> Oh.

>> That's what Mr. Shoveling give me when you got to see him.

>> You've got here too.

>> Oh, that's ...

>> Turn his badge around.

>> Oh, got around the other way.

>> Beautiful.

>> My name is Roger Astley. I live in Finchley, North London, and I was in the Royal Navy during the Korean War. I joined the Navy as a boy of 15, and I was obviously there during the Korean War on an aircraft carrier, HMS Unicorn, which transported new planes and brought back to Singapore the old ones that had all been smashed up or crashed in, whatever. We also provided new pilots for them, and we took everything up to Japan anyway, to Sasebo, including two London buses. I think it was a morale booster for the troops to see a London bus driving round Korea. That's it for me. Wait. All right? Wait a minute. Anything else you want?

>> Well, so what did you experience there? I know what you did.

>> All right. What did I experience?

>> Anything that you saw, kids, orphans or other units, Americans?

>> No, we took everybody. We even took American sailors up there on our ship, and they loved our food, which I'm afraid that the English didn't like our food, but the Americans liked it, which was quite unusual because I went on American ships, and I always thought their food was better than ours. We got on all right, and even when we went ashore drinking, and we'd had a few drinks, a few beers and was beginning to talk, we got on well with the Americans as we did with most of the others.

>> Like who?

>> Well, there was Australian troops there, Belgium. There was a Dutch hospital ship. In other words, there were quite a few other nations. The harder ones, obviously, was the Oriental nations that was there. That was harder for us to get on with them.

>> Because of the language barrier.

>> Yes, basically, whereas with the ... Obviously the most people in the world speak English away, and us English, especially myself who has an accent from the North of England, we don't speak English as good as we should do, but it was an experience. I don't think we was ever frightened. We was only attacked three times by aeroplanes, and we chased them off, but we didn't have any trouble. Apart from that, you just did your job. You just carried on doing what you did.

>> So what do you feel about Korea right now as compared to what you left it?

>> Well, I'm glad it's getting more affluent than ... It's a machine country now, I should imagine, from what it was then. In fact, I think it was the making of South Korea in a way because it's very modern in everything. It's good that they do, and their exports is good whereas I don't know so much about the North, but I don't think it's doing anywhere near as good. Even the Chinese seem to be a bit sick of them. But apart from that, yeah, I've got good memories of it.

>> You do. Have you returned?

>> Pardon?

>> Have you ...

>> I have never returned, and I always used to be amused at one of the ports we went to, I think it was [FOREIGN LANGUAGE], one of them, there was a great big notice on the roof of the warehouses, "Through this port passed the best damn fighting men in the world." That was the Americans, of course. Well, of course some of our people climbed on the roof and put, "And the Brits." And it was just a job at the time. I think because we never really got ... saw action like the Army did, to us, it was a job with a bit of restrictions in it. The ship could never broadcast its name. We all had different call signs. You couldn't let the enemy know what ships was there, so we had different call signs, but for the Navy, I don't think ... It was a few early on got killed, but most of them didn't. Most of us was too far away. It was the Army took the brunt of it, and of course they weren't professional soldiers anyway, a lot of them, as you see, there's lads had to go in for 2 years training. Well, there's people like myself and the majority of the Navy was all time-serving people. And of course when I got out of the Royal Army, where I lived, a seaside resort, I went back to sea again in the Merchant Navy where I could go to the West, to Americas and South America and the West Indies, and in other words, I had a good life.

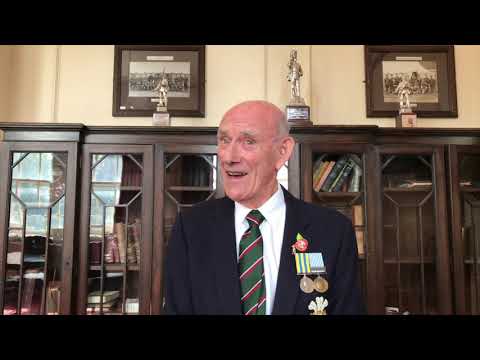

>> Richard Davie, member of the British Korean War Veterans Association. I served in Korea 1953, and I initially was posted there. I went over on a fast ship which only took 4 weeks, and when it arrived, the First US Division, Infantry Division was playing the band as we arrived in Pusan. I posted up to headquarters at the Royal Artillery, and after 3 weeks there, I was attached to the First Field Artillery Observation Battalion, United States Army, where I was sending map preferences of the Chinese guns back to headquarters. And we had six-figure map preferences or possibly eight-figure occasionally so that they could be fired upon as kind of bombardment. Questions?

>> Well, so what do you think is the British participation ... the significance of the British participation?

>> It was more or less made a direct line between Pyongyang and Seoul where the division was at the time I was there, and we had ... The last biggest battle was at the Hook, in fact, has been said that that would be the last battle of any ... with any two great armies fighting each other that the world has ever seen, the last Battle of the Hook, the Third Battle.

>> When was that?

>> That would be, ooh, right about June, May-June time 1953. After truce was signed, I went back to HQRA for a while, and then I was sent to a unit where we did all the paperwork for the prisoners of war as they were released.

>> Whoa, can you explain that? No one has ever told me about the POW process.

>> No, well, it was just our little unit. Basically because we were drawn in from several places into HQ, I think they were wondering what to do with us, so they sent us down to the center Canadian hospital unit, and all the British POWs who came through, we took down details of them, who they were, the Army number and messages for them to send home, which we wrote down, and these were coded messages because the only long-distance writing in those days was Morse code. So it was turned into code, then switched to be recoded, retranslated when it got headed back to this country.

>> And what did you do in the process?

>> Well, I was taking down the names and the addresses and everything for them, all the paperwork.

>> Have you been back to Korea?

>> Yes, went back in 2001.

>> Hmm.

>> And it's amazing, the difference.

>> Explain a little bit.

>> Well, everything is so modern and things so industrious and so going ahead with everything. My grandson went over on the UN Peace Camp last year, and as a result, he's very keen to go again, and he's just going to start a course at university in Seoul in March this year.

>> That's cool. So what do you think of the Korean people?

>> Oh, they're lovely. They're so hospitable.

>> We're very grateful, that's why, grateful for your service, grateful to the country and all the other United Nations service that fought, and again hopefully there will be peace on the peninsula.

>> Yeah.

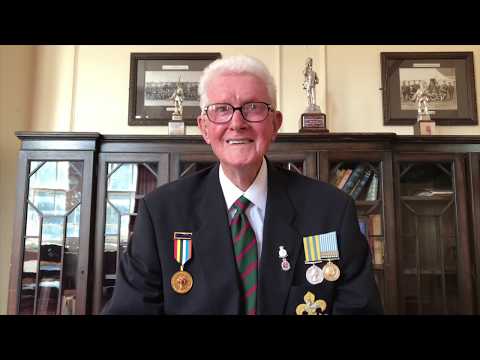

>> My name is Victor Smith. I'm part of the committee of the British Korean War Veterans Association. My position is National Treasurer who looks after the finances. We have approximately about 250 members. This was after the collapse of the original British Korean War Veterans Association, and we formed out of the members that wanted to carry. It's very successful. We're growing year-by-year. The old organization closed in 2013. That's when we started, and over ... We've made great steps in the 5 years that we were ... 4 years that we've been in operation. What else would you like me to say?

>> Just how many served from Britain.

>> Oh, the servicemen from Britain that were killed in action was 1,078. I think there was over 1,000 that were captured, and altogether, there was about 30,000 went to Korea from Britain. The reason that we only did one winter because of the cold winter, extreme cold, whenever you got there, you could only go 12 months that included one winter. The conditions were pretty basic. Spares ... I was involved with maintenance of vehicles and tanks. To get spares and equipment was very, very hard. We cannibalized one vehicle to keep another vehicle going. Any that we couldn't deal with, they were taken to Inchon and shipped to Kure in Japan where the Japanese had workshops that repaired all the vehicles. That was under the REME. I was actually a member of the REME, which is the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. They're mainly workshops, but within each unit, there's always a REME craftsman attached to the unit. I was attached to the Tower [INAUDIBLE] Infantry, and then I was passed onto the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. On my end of service in Korea, I then moved around to the Suez Canal and spent 6 months on the Suez Canal, and then I ... My 3 years was up. Anything else?

>> Have you been back to Korea?

>> I have been back the once. I hoped to go back this year. It was a wonderful experience to return there, and I'm looking forward to going back again.

>> And I'm sure when you went to Korea, many Koreans expressed their gratitude, right?

>> Oh, yes. They treated us like gods. They're absolutely wonderful to us. They're so kind, the Korean people.

>> When you see that, that the South Koreans and Koreans all over the world are experiencing, enjoying freedom, and North Koreans are not, what do you hope for the people of the Korean Peninsula.

>> Well, I hope they'll unify. I believe there are still people that work from the South work in the North and from the North work in the South. I think they travel there daily. I'm not sure, but it wants complete unification and peace, and absolutely, it's a wonderful country to visit, wonderful people. I thoroughly enjoyed my time out there.

>> When I got to Korea, they left me in Pusan. They sent me to guard company which is east of Pusan, and we were doing guard duties all around the docks, closing depots, ammunition depots, and I stayed there from September right around until February when they sent me back to the Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, First Battalion, the Royal Fusiliers, that was. That's when we stayed until the ceasefire.

>> Explain a little about that because, I mean, you didn't expect the ceasefire, but it happened. I mean, like, how did people react?

>> Well, we were just happy, I suppose, but we were due to come out then because our stay was only for a year, so we're due to come out anyway, so we came out normally.

>> Why were you only scheduled to stay for a year?

>> Well, I think everybody got a year minimum probably.

>> Well, explain a little about that because I think British were the only ones maybe, not the only ones, but with the National Service.

>> Well, I was a regular. I was in for 5 years, so it didn't fly to me, but there was a lot of National Service in there. That's why they encouraged it to 2 years when the war started.

>> Have you been back to Korea?

>> Yes, 2000.

>> Oh, for the 50th anniversary.

>> Pardon?

>> For the 50th anniversary.

>> Yes, that's right. That's correct, 50th anniversary. Now, I want to go this year again if I can with my grandson, and ...

>> What did you think when you first arrived?

>> Well, it's a big improvement, big improvement.

>> Well, I hope so because it was ...

>> Nothing.

>> ... nothing but rubbles when you left it.

>> That's right. It was only two bridges on the river Seoul. Now, there was 27 I think, 30. Big change, big change.

>> And do you feel proud?

>> I do. I do feel proud, and since 2000, I've carried your national standard very proudly and honored to do so and still carrying it. I'm going to carry on as long as I can.

>> Well I know for sure the Korean people and the people everywhere are extremely grateful for your service.

>> I'm sure you are.

>> Yes. That's why I'm, here.

>> Yeah.

>> And thank you so much.

>> Very proud to see you.

>> Thank you so ...

>> Thank you for coming.

>> Thank you.

>> Right, my name is Edgar Green, and I was in the Middlesex Regiment, which is one of the first of two regiments to go from Hong Kong to Korea. We served in Hong Kong ... Served in Korea from the perimeter of Busan right up to just below the Yellow River, then down again to Seoul, mainly walking all the time. We're very ... No transport, and the worth thing was the lack of warm clothing in October when the temperature dropped to 40 degrees below. We stopped until the Battle at the Kapyong and 29 Division was in the Imjin River, and then May of '51, we returned to Hong Kong, and that was more or less my time, and then 6 weeks in Hong Kong, and I was back to England to get [INAUDIBLE], and that was my army service there. How we looking then?

>> Have you been to Korea? Have you been to Korea?

>> I've been back to Korea nine times, and so this year, when I go in April, that will be my 10th time that I've had a birthday in Korea, which I look forward to because I remember all of those friends as they were and comrades that are left down in Busan, and that's why I go every year to see. Thank you.

>> My name is Brian Morney. I served with the First Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment, and I was in Korea for 1 year. I was stationed just south of the Imjin River, not far [INAUDIBLE] and the glorious Gloucester Hill. I was there from 1956 to '57, which was postwar, and we were the last British Regiment to leave South Korea, and we were on active service at that particular time, and during that time, we had 200-man marches through Korea, which 25 miles a day for 4 days, and we did that twice. On one occasion, we had a very, very big parade at our army camp, and that was attend by Syngman Rhee, the president at that time of South Korea, and he arrived at our camp by helicopter, which was quite an occasion for all of us. When I went to Korea, because of the state of South Korea at that particular time and the poverty that I saw, I wasn't really interested in ever coming back to Korea again ... Excuse me ... Because I thought that the people were so poor and hard done by. Sometimes, it made you cry, but I've been on a revisit to South Korea, and now I think it to be one of the nicest countries I've ever been to. The people are so hospitable and really caring, and I can't speak highly enough of what Korea has done in that short space of time, and if I ever have a chance, I'd love to go back to South Korea and to visit all you lovely people once again. Thank you very much.

>> My name is Alexander Ferguson, known as Sandy. I was in Korea during the Korean War from 1951 for 2 years. I was with Royal Electrical Mechanical Engineers doing recovering, recovering tanks and suchlike and were based in various places: Incheon, Seoul, Daegu, a number of places. And there is such a tremendous friendliness about the South Korean people, who were so kind to us. I can't ... Anything else?

>> Well, so when you went to Korea, what do you remember?

>> I remember the fact that [INAUDIBLE]. I hadn't seen those before, and the oxen who'd carry, were pulling carts about, and the A-frames the gentlemen the gentlemen were carrying about, [INAUDIBLE], and the roads, the condition of the roads. They seemed to be years and years behind the times at that time. I don't mean to seem unkind, but it did seem very, very behind times then. I'm so pleased to see how Korea has come on now. In fact, I drive a Korean car. I remember different instances, rescuing tanks and backloading vehicles in Incheon to go to Japan when we agreed it was beyond local repair. And meeting the various different sections of the army, and different ones did different things, such as RASC. We saw them doing their work, supplying stores and things, the engineers building bridges and ourselves recovering and repairing vehicles. I can't think of much else at the moment.

>> Well, what do you think about the Scottish contributions in the war? Not a lot of people know about it.

>> Well, there were a lot of Scottish people in the regiments, in the infantry regiments there, which we're very proud of, but I wasn't with any infantry, although we did rescue vehicles from Gloucester Valley. It was known as Gloucester Valley after ... There was quite a large battle there. The army were called the Glorious Glosters. Yeah. Scottish people were ... There were only a few Scotsmen in there, in our unit. I think there was three Scots in it, and there aren't as many people in Scotland as there are in England in any case, but we ... Scotland was well represented in the infantry units. I think that's all I can think about at the moment.

>> How did the war impact your life when you came back?

>> When we came back, we got about 3 months leave of absence when we came back because we had only 5 days in Tokyo while we were ... All the time we were in Korea, we had only 5 days R and R, and we went to Tokyo and to Ginza Street and Ebisu Hotel, as they called it then, but that was a nice 5 days. And after we came back home, we came back in the [INAUDIBLE], having gone to Korea on the Empress of Australia, came back in the [INAUDIBLE], and I wasn't back very long until I got malaria which is apparently because tablets weren't taken aboard the ship, so they say. Anyway, I think just about everybody on that ship, all the troops in that ship, caught malaria, and it came back once after that and has been away ever since. I had about a year to serve after I came back which I served in Scotland which was the first time I had ever served in Scotland, in Stirling, and I didn't do a lot of distant driving, really, and I rode motorbikes for the units. I represented the unit in the Scottish Six Day Motorbike Trials. Needless to say, I didn't win. I didn't get anywhere, and then when I left the army altogether, I worked initially in a garage, and then eventually I had my own business making and selling carpets, and I then retired.

>> Have you been back to Korea?

>> No, I haven't. My wife and I would have liked to have gone, and I keep thinking we should go, but some of the cruise ships ... We've been on a number of cruises. Some of the cruise ships call in Korea. It's only for a day, and I am told I should go with a group. I don't know. It's quite a flight out there, but it's quite a long flight, whereas if you're cruising then you're whole [INAUDIBLE]. That's ... Our next cruise is at the end of April to Fort Lauderdale and then somewhere and then Bermuda and back home. We really should ... We should have gone or should go, but I don't know. Maybe I'm getting too old. I'm sorry about this.

>> How old are you?

>> Eighty-six.

>> Eighty-six!

>> Eighty-six last week.

>> So you were ...

>> The day after Robert Burns.

>> So you were 22 when you went to Korea?

>> I was 20.

>> Twenty?

>> Twenty, yeah, 19 or 20.

>> Nineteen.

>> I had my 21st birthday in Korea.

>> Oh. What was that like?

>> It was good. A American camp just along the road made me a birthday cake which was very nice, and my mother sent one which we didn't get for quite a long time because of the [INAUDIBLE] and so on.

>> She sent a cake?

>> She sent a cake, yeah.

>> And you got it?

>> Yeah, yeah.

>> By the time you got it, wasn't it rotten?

>> No. No. Put the right stuff in there, it'll keep for a long time.

>> Wow. That must have been nice.

>> And then of course in Korea we had to get used to the wons for currency, the Korean wons, and the British Army [INAUDIBLE], as I recall, if you spent any army money in [INAUDIBLE] or EX, or somewhere like that, but the Korean won currency, it ... Well, 1,000 won wasn't worth anything at all. A thousand won at that time would be worth about 25 pence in UK money today. I can't think of anything else, Hannah.

>> Okay. That's okay. Well, what did you ... Did you ever meet civilians in Korea?

>> Meet who?

>> Civilians, Korean people?

>> Oh, yes. Yes. There was a little houseboy that came with us, and we would [INAUDIBLE]. I went down, did what we were going to do and came back, and the American military police wouldn't let the little boy back over. They said, "You've got to stay south." And I said, "His parents are north." He said, "It doesn't make any difference. Everybody has got to stay south," and we felt really bad about this. So we told the wee boy, "Just go down the road and stay there, and we'll come back for you." So we went, and we went back there with two trucks, and we picked him up in the smaller truck and took him further down the road a bit, and then we came to the large truck, and we put him inside the big locker in the truck and shut the lid, and then we came back and crossed, and the American MPs looked inside and all over, and, "That's all right. We'll let us through," and he'd gotten back to his parents which he was very pleased about.

>> Well, you know that the war never ended, right?

>> Pardon?

>> The Korean War never ended.

>> Yeah, that's right.

>> What do you think about that? The two Koreas are separated ...

>> That's right.

>> ... still divided.

>> It's terrible. It's ... That idiot in North Korea, it's absolutely terrible.

>> Well, I hope that in your lifetime the two Koreas will be united.

>> I hope so, Hannah. I really hope so. We met a Korean, North Korean, lady once, and we gave her some breakfast or something, and somebody wasn't really pleased. Some of the South Koreans weren't pleased about this. They said, "Don't you realize that she's North Korean?" I said, "Well, she was hungry," and that was it. But ...

>> So how many veterans are in Scotland.

>> There are only two that are going to be there.

>> Two?

>> They had the meeting on the 29th, and I was informed that basically the following day that there'd only be two.

>> How many are there ...

>> How many is there in the branch?

>> Yes.

>> Oh, a lot more than two.

>> How many?

>> Probably about 20.

>> Twenty.

>> [INAUDIBLE] and the other Scottish unit members.

>> So many other units are there?

>> Up here?

>> Mm-hmm.

>> Actually, there's none.

>> Well, it's not ... It closed down, but they keep it going as a tea and coffee social.

>> So there's right now only about 20 Scottish Korean War veterans.

>> No, there's more, but a lot never joined anything, never made any effort. You'll meet one hopefully tomorrow morning. He's from Govan, and he phoned me [INAUDIBLE] Canada that contact me, and some of his workmates in the army have moved to Canada, but they kept in touch, so they told them to contact me, and he did. He phoned me and explained the situation, so I explained it to me, so Govan is about 20, 25 miles from here, and the ... We'll be pressed a bit for time tomorrow. We could take you to Govan and other places and get you back to [INAUDIBLE], so ...

>> I know that I organized the event July 27th to commemorate it.

>> I know. Yes, I know. Korea Day.

>> But I do it on Saturday before because no one can come then if it's on the weekday, but you do it on a Sunday?

>> The nearest Sunday to the 27th.

>> Yes, I do a nearest Saturday.

>> Aye, well, the reason for that is on Sunday, well, it's a day of rest.

>> Yes.

>> So the roads are a lot quieter, and then people my age, we're older, and so a lot of them can't drive themselves. They're disabled, so it's family. We drive them, so the drive up to [INAUDIBLE] on Sunday.

>> How many gather?

>> What?

>> How many gather?

>> Oh, it can be 100, 150, something like that.

>> Oh, wow.

>> Can be that.

>> But they're not all veterans, right?

>> No, there's the relative and associates, things like that, but it's a nice gathering. We have a nice service.

>> The one in Bathgate, the memorial in Bathgate?

>> They have that in Bathgate every year, and I think ...

>> So July, to commemorate July 27th.

>> I've been ...

>> What is it called here?

>> Pardon?

>> What is it called here? Is there a name for the day?

>> Is there a name for ...

>> The day.

>> No, no.

>> Because now in America, we call it the National Korean War Armistice.

>> No, there's nothing like that here at all.

>> So only the Korean War veterans know what it is.

>> The government, newspapers, they want to know it at all.

>> Okay.

>> They ignore it.

>> So nobody from the government.

>> Oh, the government hopes we're all dying off. They hope we die soon. They're annoyed. One of my friends is in the Lords in London in the houses, the House of the Lords, Earl Slim, John Slim, and John I've never heard of him speaking. He never speaks. He just goes there, collects his money in the bank, and that's it. You've heard offer.

>> You've heard of Earl Slim. Have you?

>> No.

>> Earl Slim of Burma, who commanded the British forces in Burma during the war.

>> During the Korean War?

>> No, at the 1945 one.

>> Oh.

>> And they made him an earl, who is a general, and they kicked him up to be an ...

>> When did you serve in the Korean War?

>> 1953.

>> Oh, towards the end.

>> Yes.

>> The last 6 months.

>> Oh, before the war? I mean, before the armistice?

>> Yes. Oh, yeah. I'm a veteran.

>> So you were there when the armistice ...

>> Oh, yes. I was in the [INAUDIBLE] in the last battle of the Hook, the battle of 355.

>> Kumsong?

>> The last battle of the Hook.

>> A lot of people have been talking about the Hook. Can you explain that?

>> Yes, it was a piece of ground, shall we say, in the valley shaped like a hook. It stuck out into the valley, but it prevented the Chinese passing and the North Koreans from passing, and they wanted it very badly. They commanded that area, and they wanted it, so they always attacked it in force, and they always get beaten off with an effort.

>> What was your assignment?

>> I was a driver. I drove trucks.

>> Wow.

>> I was also signalman.

>> Oh, so was Grandpa Hoy.

>> And I was also a gunner.

>> What? They made you do all of that?

>> I didn't do all of that in Korea though, but that's what I was qualified for. I volunteered. I was in the regiment fairly early, regiment, the Royal Horse Artillery, the third regiment, the oldest third regiment [INAUDIBLE] in the British Army. It was raised in India.

>> You were raised in India?

>> No, the regiment was raised in India.

>> Oh, the regiment.

>> Yes. Oh, way back in the times of the Indian uprising and all that, and it was taken over by British government originally and incorporated into the Indian Army and then into Britain. My great grandfather was a general in the Indian Army.

>> Oh, in the Indian Army? Wow, what year?

>> Pardon?

>> What year? When?

>> Oh, in 1800s.

>> Wow.

>> Yeah. He was a friend of Queen Victoria.

>> Wow.

>> Yeah. She liked him very much, and ...

>> What his name?

>> General Sir William Riley.

>> Wow, the Indian Army.

>> Yeah.

>> I know the Indians ... Because the 68th Parachute Ambulance.

>> Yes.

>> Right, is that right?

>> Yep, yeah, yep.

>> Correct, 68th.

>> They were there.

>> Do you remember them?

>> Yes, yep. They stuck needles in me from time to time.

>> The medics?

>> Yes, yeah.

>> So explain the armistice and the battle and just right before the armistice and after because you stayed until when?

>> I was there [INAUDIBLE] in November. Well, we set sail Christmas Day in the Indian Ocean. That was December.

>> December, 2000 ... I mean 1953.

>> You were there for 1 year?

>> [INAUDIBLE].

>> But you saw the ... That must have been so interesting. You saw the height of the war and the largest scale battle, right, right before. I don't understand. I heard that the armistice was signed, but they thought that they would negotiate a peace treaty soon after, right?

>> The peace treaty never ever took place ...

>> I know but ...

>> ... just a cease fire, an armistice.

>> But they were going to negotiate it, no?

>> No, they wanted to replace it soon.

>> Maybe the American government wanted to do that, but certainly the Chinese didn't want it, the North Koreans. No. There is actually ... There is so much been written about the Korean War.

>> You said so much?

>> Which does not get any publicity in Britain. As I've said to you, British government would rather we all die. A lot of our members got or was exposed German warfare. I don't know if you know that, but the government [INAUDIBLE], and probably that is the reason why most of our casualties are all dying off with cancer. Yes. The incidents of cancer in the Korean War veterans is higher than in the general population.

>> Really?

>> Yep.

>> What kind of cancer?

>> Every kind.

>> Really? Because I know in Vietnam because of Agent Orange ...

>> Oh, yes, Agent Orange.

>> ... that a lot of Vietnam war veterans have cancer, but I've never heard of Korean War veterans having cancer.

>> Oh, yes.

>> In Australia, Canada and America and New Zealand, if I remember correctly, they all acknowledge it. The British government will not acknowledge it. There was a British woman whose husband died, and she had heard about the Australian people making compensation, so she started a case up, and she won. Took a while, but she did win compensation, but they never agreed that it was caused by the Korean War. You can imagine if everybody had cancer started claiming. What kind of money would be we be talking? It'd run into millions.

>> I wonder what about the Korean War caused cancer.

>> You need to ask the American government. When you go to Australia ... You'll be going to Australia, won't you?

>> Yes.

>> You must contact Haning Spicer.

>> Okay.

>> Have you got the name? Haning Spicer. He's gone all over Australia which has [INAUDIBLE], and that's because of his service for the veterans [INAUDIBLE] but ask Haning about it. He'll tell you a bit more, so the consequence, I reckon, of it, and when I was in Canada, one of the men who became an officer was talking about it with an American general there, and they were [INAUDIBLE] was cleaning his boot with it, and I wandered over to see what it was about and saw them [INAUDIBLE] screws, and they said, "Yeah, we know, but the sides are all wood, and that's why we're going to construct some metal, and we're thumping it in with a hammer," so that was introduction, and we became friends, actually, and he said to me, he says, "Arnold, [INAUDIBLE]." I said, "Yeah. I've got tons of it. How much do you want?" He says, "How much can you get me?" I said, "What do you want?" He said, "I've got [INAUDIBLE] war, and I've got no ammunition for it?"

>> Do you keep in touch with him?

>> Oh, yeah. I still keep in touch with him.

>> Oh, wow, and still lives in Nebraska?

>> Yes, Central City.

>> Why is the memorial here in Bathgate?

>> Well, it was built or organized and paid for and built by the Bathgate branch. It was a much bigger branch then than it is now, so no government money was ever applied to any memorial, although the defunct organization, the BKVA, when they quit, closed, they gave £1,000 to help refurbish it.

>> Oh, when was it built?

>> Pardon?

>> When was it built?

>> Oh, I don't know exactly. It was some time ago, a few years ago anyway. Yep.

>> Like in the 2,000s, like in the 1990s, '80s?

>> Yeah, yeah, yeah. I would probably say late '90s, early 2, but up on MacKenzie up here will be able to tell you all that. You'll have a difficulty in stopping him telling you actually.

>> I am Adam McKenzie. I'm a member of the Bathgate branch of the Korean Veterans Association. I served in Korea from 1950 to 1951. I was stationed in Hong Kong when we were first told we were going to Korea. Nobody knew where Korea was. We boarded a Royal Navy ship and 4 days later arrived in Pusan. At that time, the Korean Army and the American Army were the only United Nation troops present in Korea, and they were [Indistinct] in a river called the Nakdong. We were moved up to there, and the Royal ... the Middlesex regiment and the Third Australian regiment, who were joined us just days later, crossed the Nakdong and made the breakout from it. That is why we have the only medal for the defense of the Nakdong. That medal, there was under 3,000 people entitled to wear it. It was the Middlesex regiment, the Third Australians and the Argylls. There is under 100 of us left today. After the breakout in Nakdong, we progressed up through South Korea and though we were probably 30 miles inside North Korea when the powers that be stopped us and ordered us to be dumped in 38th parallel.. During that time, the Chinese Army came in, and because we were on withdrawal, instead of the attack, we got pushed frankly back to where we started again. However, we started to regain country again, until we handed over to the King's Own Scottish Borderers in June 1951. We then returned to Hong Kong. [INAUDIBLE] got into any episodes that happened during then.

>> [INAUDIBLE] you went in with no winter clothing.

>> We had no winter coats. We had no winter clothing. We left Hong Kong thinking Korea was a tropical country, which it is during the summer, but not during the winter. We had no ordnance supply whatsoever. We were fed by the Americans. For clothing, bedding, etcetera, we begged, borrowed or stole off the Americans and the Third Australians. And we managed to live that way for a year. The Americans fed us. The only thing we had supplied from the British government was ammunition, nothing else. And we managed to survive for a year, and we were one of the only regiments that never lost a man with frostbite, although we had American dikes crossing the river which was frozen solid. Our vehicles sometimes were frozen in the morning when you tried to move them, etcetera, but we survived. Now basically, there's various episodes we could talk about. Like, Sariwon is one. We arrived at a town called Sariwon at approximately 3 o'clock in the afternoon. We asked for American tank support to take the town. The Americans said, "No, it's too late. Our tanks will be coming into town in the darkness, and we'll lose them." So we went into Sariwon without the tanks and took the town. The Third Australian then marched through us and took up a defensive position in front of Sariwon. We returned to the other side there and met the North Koreans and the Chinese coming in on the back wood. Because we were facing the wrong direction and we never wore steels helmets or anything, we wore a scarf tied up on our heads, they mistook us for Russians. And we back marched them, came round the back, contacted the Third Australian Regiment. We turned to face the opposite direction. We came in behind, and we took over 3,000 prisoners without firing a round of ammunition, nice. A very big problem for us was on the 23rd of September, 1950. On the 22nd, we took over a hill called 282 from the Americans who had been sitting on the hill for approximately a week and couldn't move off it. We took it over the 22nd, and on the 23rd, we put an attack in. Because the maps, etcetera, were so out-of-date and inaccurate, we didn't realize the next feature overlooked it. We took Hill 282, realized we're in a position where the enemy could look down on us and fire down on us, so we called for air support. Now air support was supplied by the Americans. We were supposed to put things out as air recognition panels. They were red, yellow and blue, and you put them out each day in a different design on the reverse of the hill. We did this. The Americans because they'd been dropping everything for 7 days on the one feature, came straight in and dropped the same load. The only problem was we were underneath it. We lost nothing, not one. Major Muir, who was our second-in-command, won Victoria Cross. It's a day we will never forget.

>> Why is there a Korean War Memorial in Bathgate?

>> Why is the memorial in Bathgate? Well I'm going back 20-something-odd years, and we decided we would do something, and at that time, I was the area rep. I covered the three branches that was in Scotland: the Northern Branch of Inverness, the Perth Branch and the Bathgate Branch. And I went to Birmingham for an executive meeting, and you had to put your propositions in 21 days before you attended. To me this was foolhardy because it gave the executive committee time to contact all the members, discuss it and make up their mind what we're going to do. Now there was only 13 area reps, but there was 22 executive members sat on the table, so if they disagree with you, you could be outvoted without any problem. I went down, and the proposition I put in that we were going to build a memorial was read out, and the chairman General Gadd, told me I was mad. I would never get it off the ground. All it done was reinforced us. I came back here, and I told all three branches that I was wasting my time and their money because it was pointless of me to go to Birmingham to the meetings, and that I resigned as area rep. We then we got together and contacted all the local councils, etcetera. We done collections, etcetera, and eventually we built our first memorial. In hindsight, we done it wrong. We didn't have sufficient capital to build what we wanted. However, we decided to go ahead with it, and we built it. And after we built it, we realized it wasn't really what we wanted. So we carried on, and we collected more money and funds, and almost 4 years ago, we knocked down the old memorial and rebuilt a brand-new one. Now since we built this new memorial, and [INAUDIBLE] put us down to one man, we brought a roofer all the way from Korea to put the roof on our memorial. All the tiles, etcetera, on it came from Korea. This man came and spent 1 week. The roof weighs over 4 tons. There is not one nail, one drop of cement in the whole building of that roof. And I think, by what I've heard since, he must obviously have spoke to people back in Korea after he returned there because we are getting feedback from the people in Korea who ... Yeah. That's basically ...

>> That's amazing.

>> You remember his name?