>> Okay. I’m Alan Everett. I’m not Australian. I came from England originally. I served in the First Essex Regiment, and in those days, in 1952, all the British men at the age of 18 conscripted, and so I was conscripted, and I elected to stay in the army for 3 years rather than just 2 years National Service because that was half pay, and I served in Germany, then Korea and then Hong Kong, so that was my 3 years which was spent mainly overseas. I was very fortunate in my training because I was trained to be a signalman, so I went to the School of Infantry in England, and in that School of Infantry, all the officers and NCOs all combined in their exercises, so it was quite an all-embracing training, so I then went to Germany, and then my battalion got moved to Korea, and we arrived just after the ceasefire, so I’m not a peacemaker. I’m a peacekeeper. So we were stationed on the southern bank of the Indian River for 12 months, and that was incredibly cold and incredibly hot, and we didn’t get to see much of the people because we were in a defensive position, and so most of the stories we heard were from the previous people who had been through the war itself, so that was quite a challenge, and I found since I left the army and I was trained in Hong Kong, as a national servicemen, you’re allowed to get some retraining to get back into civilian life. I wanted to go to agriculture college, and I had to study chemistry to meet my qualifications, so I went to the Royal Agriculture College at Cirencester in Gloucestershire, and I did my course there. Farmed in England, met my wife Nicole who you’ve met, and we had been together for 8 days, and then I came out to Australia, so that was quite [INAUDIBLE], and when I arrived in Australia, I got myself a job. It was great. A year later, I rang up and proposed to Nicole, and she came out with her mother, and we got married over here, so quite a different story to what you expected, I guess. So my servicing career, I did so much there because I was working in the signals office, and being part of the brigade and the companies that reformed our defense positions, so I was in contact with people all the time, so when the opportunity here came available for to be a secretary for the Korea Veterans, I offered to take that job on, so I’ve been National Secretary for 8 years, but I haven’t been involved in the war side of the whole thing. The impact of the Korean War hit me when I had been here some time because the Australian soldiers that came back from Korea were not recognized as having been part of a war, and they were actually refused entry, particularly in New South Wales, to go into the returning servicemen’s clubs. They said they weren’t eligible to be members, and that took some time to overcome which is very sad, but that’s the sort of reception the Australian soldiers got when they came back to Australia. We didn’t have that in England. We just went back, and we just got on with our jobs, and it was no problem. Here in Australia, in Maldon, every year, we have a church service run by a Korean church in Maldon, and we have one of our biggest attendances of the year. We have about 90 people turn up, and about a good half of them will be veterans, [INAUDIBLE] one, and one day I was standing next to a father with his little Korean boy, and the little boy talked to his father and said, “Why are all these people here?” His father thought for a bit, and he said, “Well, without these people, I wouldn’t be here. Your family wouldn’t be here, and you wouldn’t be here.” I think that says it all. It’s such a moving experience to me. I found that quite fascinating, and the Korean community here are so helpful and want to look after the veterans as we get less and less, so it’s a beautiful encounter, that was. Now, we’ve given you the background to the memorial in Queensland, in Cascade Gardens. To me, that is the most beautiful memorial that anyone could make for any country. It’s a tribute to the people of Korea as well as the veterans from all nations who served, and when you see it, there’s a whole history that goes with it, but it’s well worth it, set aside in a beautiful park, and it depicts everything that is Australian and Korean. It’s just so well … And then, there’s another little memorial in Alexandra Heads, which a small association got formed in Queensland and the Sunshine Coast, and they made it specific for their veterans, so they’ve got this wall, and when one of their members dies, they put a brass plaque on the wall with his name and his service record on it, and I think that’s another one of the best memorials I’ve ever seen, so that’s my story.

>> My name is Brigadier Colin Kahn, retired, of course, and I served in Korea in 1952 as a lieutenant platoon commander of an infantry rifle platoon, but before I say a few more words about the army, let me explain a little bit about this memorial, which I was on the planning committee, which we helped build when it was completed in the year 2000. This memorial is located in in our avenue of memorial called Anzac Parade. Anzac Parade runs from in between two major buildings in Canberra. The Australian War Memorial at the far end of the parade where veterans of all wars are honored, particularly on Anzac Day on the 25th of April. The other building it joins with is our Parliament House down on the right-hand end, and Parliament House looks up Anzac Parade and right to the War Memorial. We hope that the politicians will see a little bit looking at these memorials of what decisions they made and what some of the consequences of sending out troops and people to war.

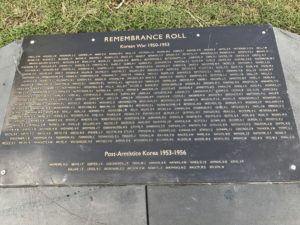

Anzac Parade is our parade, I say, of memorials, and all people, veterans and relatives of past wars like the Boer War, World War I. Most of the veterans are all dead, of course, but their relatives walk and march here, and they go up Anzac Parade to the Boer War Memorial where a service is held on the 25th of April every year. Now the memorial itself, I say, was finished in the year 2000, and the money to build it was given by the Australian government, by the South Korean government, by all our Korean and returned servicemen organizations around Australia. It took some time to build, and we had our committee navy, army and air force, and I represented the army, and women and widows of people, of soldiers who had died. It consists of out on the front an obelisk, an obelisk which is dedicated to all those who are buried without a known grave, and we have some of those. There’s an inscription on that obelisk which comes from the war cemetery in Busan, and put that inscription on the obelisk. Now the obelisk itself then leads onto a walkway, which runs up to the main memorial itself inside the memorial, which we call a contemplative space, it is where people can come and lay wreaths and where, on special days, units will come and lay wreaths and bring visitors to wreath and see what Australia’s part was in that war. On the outside of the memorial, we have listed all the 21 countries that assisted South Korea during the war, and three badges of the Australian Army, Navy and Air Force and the badge of the British Commonwealth Division. We in the army served under the auspices of the British Commonwealth Division. Also, you can see on the scroll there all the nations that served in the war. Outside in the space out here, you will see there are three statues: one of a soldier over here, one of a sailor and one of an airman. That represents our three combat services who served in Korea. Beyond that, probably note there are no symbols to nurses here, but the Nurses Memorial is directly opposite us on the other side of the road, but they’re not here. Now these statues here are interspersed, or covering them are a series of stainless-steel poles. Some people think they represent all the dead, and, yeah, we had 250-odd killed in South Korea, but they are just indicative of it. The other thing the poles do is give us an indication of the starkness of the cold which we soldiers in particular remember of some aspects of the terrain in Korea, and they cast long, gray, cold shadows in wintertime, and that really reminds us of Korea. Also, there are some boulders, and I’m sitting on one here. They were donated by the Korean government, and they were flown back from Korea from the area around Kapyong, where we had a major battle, and placed here. Now this particular memorial, I say, is used on Anzac Day, but also units come here and have their own specific parades, army, navy and air force, and then march up Anzac Parade towards the main memorial, which is dedicated to all Australians who fought in all wars in which Australia has participated. All right? Now let me give you a little bit about the army. Know we had 17,000 Australians who fought in South Korea during the war from ’50 to ’53. There were over 200 and almost 250 killed, 1,300 almost wounded, many seriously with limbs blown off and things like that. We had four taken prisoner, and a number are still buried in graves that are unknown. As I said earlier, the majority of our dead are buried in the Korean cemetery in Busan. Now the army had three battalions that served in Korea. I served in the 1st Battalion, and, you know, you can pick up all the detail of what those battalions did. There were two phases to our war. There was what we call the mobile phase when one battalion, which came over from the occupation force in Japan, participated from October 1950, at almost the beginning of the war, and it fought all its way up the peninsula, the Chinese border, and then withdraw back again when China came into the war and helped established our peace line just north of Seoul. Two other battalions we said came in the later 2 years of the war, and I belonged to one of those, and I fought in what was called the static phase. The static phase of the war is with the war patrolling where every night and during the day sometimes, we would send our fighting patrols to attack the enemy. We’d send out ambush patrols to ambush the energy, reconnaissance patrols to recognize or hear his positions because we were located on opposite sides of the valley, the Samichon Valley. The Chinese and North Korean positions were on one side, and our positions were on this side, and we had to find out what was going on, on the other side, so we’d send patrols in to find out. This patrolling activity got particularly intense in October, November 1952, and with my battalion, which was called the 1st Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment, we had a big hill in the middle of our area called Hill 355 or Maryang-san. It was vital ground. Vital ground means if the enemy captured it, they could almost control what’s going on all around it. One of the United Nations battalions, not an Australian battalion, was attacked very heavily up on this particular hill and almost overrun, so my battalion was sent up the next day to reoccupy the position and try to regain the initiative in the patrol battle. My platoon of 30 men, we were given the forward platoon, close to the enemy positions, and we had an intensive patrolling program where every night, we would send out half of my platoon. My platoon sergeant might take it out from last light until midnight, and then I would take the rest of the platoon from midnight until dawn, and we’d either have fighting patrols or ambush patrols to try and get the enemy as he was coming across to our positions because the name of the game was to control no-man’s-land, and this is why this position was overrun before we got there. The battalion that was there before we arrived did not patrol actively, and the enemy, the Chinese, came across no-man’s-land and dug tunnels at the base of this big hill, 355, and infiltrated soldiers across over several nights, and they occupied this position at the base of one of our positions, and they weren’t interrupted, which means that whoever was on our side wasn’t patrolling actively enough. They all should have been picked up and destroyed long before this, so when they decided to attack the hill, they were already on the hill, and our artillery and mortars had no effect on them, so they did overrun several of the positions. Anyway, a lot of the positions on this hill were destroyed, and we were sent up to reoccupy and take it over, and this is when we did all this active patrolling. Now let me tell you a story about one particular patrol, which I always remember, was a patrol which occurred that I was leading on November the 11th, 1952. I remember November the 11tth because it was Armistice Day, not for Korea, but it was Armistice Day for World War I. My platoon was under heavy artillery and shell bombardment all through the night, and we were supposed to leave at midnight, but we couldn’t get out of the position because there were too many shells falling, and we couldn’t expose ourselves out of the trenches. I managed to get the platoon out sometime after midnight, and we started to go down the hill as a fighting patrol to start to see if there are any enemies still on our hill. Halfway down the hill, we ran into an enemy ambush.

The enemy opened fire, and I was hit with a machine-gun through the chest, and I had three bullets which went through my chest. Then they threw hand grenades, and fortunately I was wearing a United States armored-proof vest, and that stopped all the grenade shrapnel, but you might ask, why didn’t it stop the bullets? Well, the bullets happened to go through the vest, the zipper, which was in the middle of the jacket, and these three bullets went through the middle of the zipper and caused all my casualties. I must say. The next morning, when I was in an American MASH hospital, American scientists visited the hospital and said, spoke to me about my action, and they decided then they had to change the design of the armored-proof vest, of the armored vest from having a zip down the middle. They put the zip under the arm, and I said, “That’s a good idea. I wish I had have had it.” Anyway, I had an interesting experience when I was shot, and it was, you know, severe wounding. I had an experience where I left my body and went up into the sky, and I was in no pain.

I could look down on the battle that was taking place with my soldiers and the Chinese soldiers on the ground, and I could see this battle taking place that I was divorced from because I was in the sky, and I suddenly realized that if I didn’t do something, I might die altogether because I shouldn’t be doing this. I should be in pain on the ground, so I forced myself to come back to the ground, and I did. I managed to come back onto the ground, and after that, my own stretcher-bearers got me and took me back to my lines, so that was my experience with an out-of-body, out-of-life experience, which I’ve had in South Korea. Now my evacuation also shows what happened in Korea.

When I was wounded in this no-man’s-land area, I was carried back to the Australian aid post in our battalion by Australian stretcher-bearers. One of those stretcher-bearers happened to be a man named Keith Payne, who eventually won a Victoria Cross, our highest award for valor. However, at my battalion aid post, I was then picked up by an Indian field-ambulance, which drove me to a clearing station. Then it was another Norwegian base picked me up there and took me to American MASH, and the MASH was 8055 MASH, which is the one you see on television every night. It was all taken at the MASH I was in. After I was treated in the MASH for several weeks, I was then taken by a bridge hospital train down to Seoul into a British hospital, then flown by an Australian medical aircraft across …

>> …threat. I’m Norman Lee. You want to know when I was first in Korea, October 1951, flying from an aircraft carrier from the Royal Australian Navy, flying Firefly aircraft. Our task was interdiction, which meant we had to keep all the roads closed, and our weaponry was bombs, so we did a lot of bombing of bridges, et cetera. Interestingly enough, we found that you can bomb a bridge, straddle it, and the bridge is not damaged. Am I going into too much technical detail here?

>> No.

>> No. So we decided to do low-level bombing with delay fuses, a 27 delay between the bomb hitting the ground and exploding, four aircraft. Me, the last aircraft in, I had to get in within 27 seconds. Obviously I did because I’m still here. Interesting things, we operated out of Guri, the carrier, out of Guri and Sasebo. We alternated between the two. We were on patrol for 10 days in the Yellow Sea. We alternated with American aircraft carriers. We were there for 5 months.

We relieved a Royal Navy aircraft carrier, and it came back and relieved us. It went down to Australia to be refitted. Highlights? I remember taking a group to Iwakuni to do a test flight on an aircraft, and on the way back, we were still in uniform because it was still wartime. We stopped at a Russia bar, and it was still dead flat, and we wandered around. We were looking for somebody to get something to eat like today, and we came across what we thought was an eating place, and we walked in, and obviously we weren’t very welcome, and it turned out that it was a private place, and then they realized we’d made a mistake, and then they welcomed us. They took us out the back, sat us down, and we had a cow sukiyaki as they called it, lots of acai beer, and then they put us onto the train back to Guri so good fun. Highlights? We went through a terrific typhoon, Typhoon Ruth. We lost aircraft off the flight deck because of the weather. The flight deck is 44 feet above the water level, and we lost a tractor off the front of the island and a boat from behind the island, so you can see how the waves at 44 feet were [INAUDIBLE]. The ship rolled 35 degrees, which is a lot of rolling in an aircraft carrier. What else can I tell you? Ask me a question.

>> Do you remember seeing some of the civilians?

>> Oh, yes, Korean. Interesting, I took the mail from the ship into Gimpo, and as a result, I went into Seoul. In Seoul, there wasn’t a building standing that didn’t have a hole in it, and the only bridge was in the river, in the Han. And when I went back about 15 years ago, multistory buildings and, what, 17 bridges across the Han now, very prosperous country. Two of my course mates were shot down during the Korean War. They both survived, very interesting. We lost 10 aircrafts, shot down. We lost three pilots killed. We incurred 90 instances of damage to aircraft in the aircraft fire. Anyway, when it came time to come home we did. We arrived in Australia and as if we had never been away. There was no … not like Vietnam where there was lots of anti. It was just the flow. We’d never been away, and we went straight into peacetime routine, and that was that. What more can I tell you?

>> So …

>> I’ll tell you a little interesting story.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> We had destroyers and frigates, surface ships, operating all the time, and you would have seen pictures of the Thames in London. There’s a cruiser sitting in the Thames, HMS Belfast and Tobruk. Tobruk was an Australian destroyer, and Belfast was a Royal Navy cruiser. We were on the east coast doing shore bombardment where the pilot directs the fall of shot from the ships. All right? Are you still with me?

>> Mm-hmm.

>> Good. Stay with me. Anyway, exchange of call signs between the ship and myself. Went ahead shooting. I made corrections to their fall of shot, and there was a problem. The ship had to come closer. Something was awfully wrong, and it turned out I was correcting the shot from the destroyer on the cruiser’s fall of shot.

>> Mm.

>> White phosphorus, Willy Peter, does this make sense to you?

>> Yes.

>> Anyway, about a year later on back in Australia, we had the Navy officers out to lunch, and their gunning officer said, “You’re an aviator,” and he said, “I’ve met the biggest idiot aviator in Korea.” That was me. Good story.

>> Did you tell him it was you?

>> Now, during the talks, truce talks, we were on the east coast at Hungnam, which is on down the east side. We normally operated on the west side. And the word went round the truce talks were almost going to happen, and we were given a code word, and the code word was Brandywine. And if we heard the code word … We were flying. Heard the code word Brandywine, stop bombing, rocketing, whatever you were doing because the truce had been declared. And the joke went around the squadron that if you had just dropped a bomb, you’d better duck down and grab it before it hit the ground. Joke. We need to worry because it was, what, 18 months, almost 2 years before we finally had a truce. Yeah. Now my reaction to being there? I could remember one time forming up, flying back from a bombing mission on my leader, and I suddenly had a thought, “What am I doing here 10,000 miles away from home bombing these people?” And that was it. I mean, anytime I ever thought about it … When you’re 21, it doesn’t matter, does it?

>> So have you thought about that question now?

>> No, doesn’t worry me.

>> Well, I’m glad you made it home safe.

>> I did, didn’t I? Obviously.

>> And you stayed in the service for a long time until you retired as a commodore.

>> Yeah, 33 years. I had commanded three ships …

>> Mm.

>> … which is good. So I was both an aviator and a seaman officer.

>> Since you were with the Navy for a very long time, what do you think the significance of Australia’s Navy was in Korea?

>> Then?

>> Mm-hmm.

>> Not that great really, the surface ships, I mean. The carrier, yes. We certainly … We did as good as what the Americans and everybody else was doing, including 77 Squadron. But the surface ships, all they could really do is gunfire ashore. It wasn’t a great effort. Well, I better clarify that. They were there from the beginning until the end. We rotated ships through in support as you would do, and some of them were pretty heavily involved, but not like the second World War.

>> Of course. The Second World War was a little different.

>> That’s a little different.

>> And so many more died, and it was …

>> Yeah.

>> It was a little more grander in scale, but it is true that the Korean War was a united effort of more different people from different continents, and I would think that Australians, coming from Oceania, as you said, 10,000 miles away and yet still participating in this war, you may have wondered why. But if you look back, it was really … You defended the freedom of South Korea.

>> Well, I think, looking back on it, we very much recognized the United Nations concept, and if the United Nations said we’ve got to go to war, we went to war, and it really was as simple as that. That’s my opinion. What do you think?

>> Yeah, I became very sympathetic to the South Koreans.

>> Yeah.

>> We’ll do his shortly, but yeah. I mean …

>> Since then, Australia has been involved in wars it should not have been involved in, right?

>> Mm-hmm.

>> The Korean War was a legitimate action. There’s no question about that to me.

>> Well, it stopped the threat of communism all over in that region.

>> So they say, and we’re led to believe.

>> You can tell for sure. I mean, there’s a stark difference between North and South Korea. You know what you fought for. It’s one country, I mean, one people, but the Allied helped South Korea and took down North Korea. I hope that you’re very proud.

>> Well, yeah. I’ve accepted that’s what we should have been doing, and that’s what we did, and you’re right. I’ll tell you a final funny. Do you want to hear a final funny?

>> Yes.

>> On the flight deck of the carrier, having started the aircraft, I couldn’t get my gun sight to work. No gun sight, and I fiddle with it, and I change the bulbs in it, and still no gun sight. And off I went, and we came across some Chinese, and all I could do was sort of point and spray, right? Right back on board the carrier, and I was sitting in a little cafe behind the island with my air group commander, the boss. There was a knock on the door, and a petty officer came in and said, “[INAUDIBLE] Lee, we’ve found out what’s wrong with your gun sight,” and I said, “Oh, good, what? Bad maintenance?” “No, no, no, no, sir. The brilliance was turned right down.” Good story? Naughty, naughty it was, too.

[ Chatter ]

>> It’s amazing now, isn’t it?

>> I am Milton Cottee, retired from the Air Force. I’m 90 years old, and I did my flying training in 1948 and ’49, after World War II. I was married during World War II, and that is significant to something I’ll say a bit later. After I completed my flying training, I was posted up to the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces in Japan to a place called Iwakuni where our squadron, No. 77, was based, and that posting was to have been for 6 months. Towards the end of 6 months, I decided to bring my bride up to Japan, and she arrived on the 28th of July, 1950. Sorry, 28th of … well, 2, 3 days before the war started, which was, yeah, June, June, yeah, June. Anyway, so I had my wife with me, and she shared all of my experiences during the Korean War. On the 25th of June when the war started, our squadron was put on immediate standby about 4 hours later because we were part of the United Nations’ battle group, and we were asked to go on standby. We armed our aircraft and got them ready for war. However, our government’s approval was necessary before we could get involved in the war, and that took 2 weeks, 2 weeks where we were waiting and learning as much as we could about where Korea was, and how could we get there and what was happening, so we were all apprehensive as to what was to happen. On the 2nd of July, asleep in a married quarter on the base of Iwakuni, a phone call woke me up at about 2 o’clock in the morning, and a voice said, “Milt, our government has approved us to go to war. There will be a jeep around to pick you up in 1/2 hour. You’re off on the first mission. All you need is your flying suit,” so I had to get up and leave my wife behind and go to war. It was the first time that I’d flown a Mustang at night, which was quite an experience, and our mission was to give top cover, top fighter cover, to DC-3 aircraft or Dakota aircraft that were evacuating civilians from Taejon in the middle of Korea. We flew across the sea towards Korea, and we normally flew a section of four aircraft. Very rarely did we fly any fewer than four aircraft in one section. One aircraft had to turn back with radio trouble, so that left three of us on the mission. We were fueled up with fuel in every conceivable tank, and our aircraft were consequently unstable. We had full guns at 2,500 rounds of .5 ammunition in the six guns, and we were ready for air-to-air combat. I had had very little training as a fighter pilot in that role and was wondering how I was going to manage. As we approached the coast of Korea, one of the members, number three, surged forward, and we wondered where he was going because we were normally in a formation, and the leader called up and said, “Where are you going, Tom?” And then the penny dropped. He wanted to be first into Korea, and he was. We chased him, but we couldn’t catch him before he crossed the coast. Anyway, it wasn’t a very successful mission. We found an airfield which we thought was the right one, circled around it for a long while and then went back home to Japan. My third mission was very eventful. We checked in with a control center and were given coordinates to go to, which was to a little place called Pyeongtaek just south of Seoul, and that’s where the bomb line was. That’s where the enemy had advanced to at this stage, and there was an airborne forward air controller giving us directions as to what to do, but we contacted him by radio, and we were about 10 miles away from him when he suddenly called up and said, “Little friends, little friends, come, hubba-hubba. I’m being attacked.” Now little friends is a name for Mustangs which derived out of World War II because they were escorting bombers into Germany, and the bomber crews called them little friends, and hubba, hubba is come quickly, so it was a funny mix of language that we heard on the radio. I was the first to see the other aircraft that was supposedly unfriendly, and I thought, “Well, I’ll have to shoot him down.” He was much lower than I was, and I chased him, and I was just about to fire with a no-deflection shot, which would’ve … couldn’t have missed him when he yawed out to one side, and I saw South Korean markings on the side, and I refrained from shooting and pulled up thinking that maybe it was a North Korean in South Korean markings, so I didn’t want him to have the opportunity to shoot at me, so I pulled way up above him and looked down while I was upside down and eventually determined that it was a South Korean aircraft that had come out of the sun to have a look at the airborne forward air controller. Now, back to the forward air controller, who had as targets or had had as a target a little bridge over a little river near Pyeongtaek, which he wanted to us to knock down. Now the armaments we had were just 3-inch rockets with 60-pound explosive heads, and we thought that they would be rather ineffective against a bridge. Nevertheless, as we started attacking the bridge, tanks were coming down the highway, and they were firing at us, so I diverted away from one attack to fire at the tanks, and at that stage, we hadn’t worked out that the best way to hit a tank was from the rear, and I was firing at them from the front. Anyway, it stopped the tanks from progressing down the highway, and then we tried to knock the bridge down, expending all our ammunition, and then we didn’t have enough fuel to get back to our base in Japan, so the forward air controller said, “Well, you can come back to my airfield at Taejon,” and we followed him, and it was late in the even and getting dark, and by the time we landed at this little airfield at Taejon, it was crowded with aircraft of all types, and we had hardly a place to park our aircraft, and here we were, three Australians in funny-looking flying suits which had been made Japan. They were actually white at the time, and we were carrying around a Mae West and a .38 revolver, and we were trying to get a message back to our base at Iwakuni in Japan. We found a communicator who wouldn’t take our message so … because of higher priority traffic at the time. We could hear artillery in the distance, and we wondered whether we would be overrun in during the night. We found a place to sleep in an empty house, and the next day, we foraged around for something to eat. The Americans on the base didn’t know that Australia had entered the war, so they were trying to get us to do things that we didn’t want to do. Anyway, we didn’t … We had to get some fuel, so we found an airman with a fuel tanker, and he didn’t want to give us any fuel because of the shortage of fuel, and I traded my revolver for a tank of fuel, and that was the way we got back home. Anyway, because of that, the leader that I had normally flown with had flown on another mission with someone else, and he was our first casualty, and if it hadn’t been for the fact that we had been delayed from getting back to our base that night … He launched the next day, before we got back to the base, and he was our first casualty. He flew into the target and was killed. That upset us to no end, and shortly after that, we lost our commanding officer, and we then progressively lost more and more people. We lost something like 41 pilots and many more aircraft. The missions that I flew early in the war were hectic because the enemy was advancing regardless of what we were doing. We were trying to stop them all the time, and when they got down as far as the Nakdong River, General MacArthur, the overall commander, said, “Hold the river. Don’t let them cross the river,” and we fought valiantly to help troops on the ground, who were on one side of the river and enemy on the other side. I found a bridge across the Nakdong River at a place called Chilgok, and I had two 500-pound bombs, and I thought, “Well, maybe they will want to cross the bridge, so I’ll knock it down.” I tried to hit the bridge with my two bombs, and I missed fortunately because several days later a message came down from General MacArthur’s headquarters saying, “That bridge is off-limits because we want to take an offensive shortly, and we want to cross the river on that bridge.” Anyway, that bridge is still standing even though a new bridge has been built beside it at Chilgok now. Now I have been back to Korea a couple of times since the war, and the battle of the Nakdong River is quite a classic. We were able to hold it. A funny incident occurred while we were doing that. We were flying from a place called Taegu, which is now called Daegu, and it was a very active airfield, and we would fly across from Iwakuni in Japan with a load of weaponry and deliver it and then refuel and rearm at Daegu, and one of our targets given to us out of Daegu was a railway tunnel in which North Koreans were putting supplies and men to hide during the day, and we were to knock down the entrance to the tunnel. We had rockets, and to get rockets onto the tunnel mouth, we had to fly very low along the railway line approaching the tunnel, bearing in mind that there was a hill to go up and over when we fired off our rockets, and after a while, we were getting out the odd rocket down the tunnel, and every time a rocket went down the tunnel and went off inside the tunnel, there would be a huge smoke ring come back out of the tunnel, and this amused us very much, and from then on, it was a competition to see who could blow the best smoke ring. And of course we were very effective in knocking out whatever was stored in the tunnel. We knocked down bridges. We knocked down gunning placements. We strafed dug-in troops. We had no rules of engagement actually. I wasn’t aware of any rules of engagement. We made up our mind as we went along. In wars these days, you have rules of engagement. You can hit this, or you can’t hit that, that sort of thing. I feel very sorry for many of the citizens of South Korea because often we would be tasked to fire at people on the ground that had enemy mixed in with the local population, and that leaves me very sad that we had to do that. In fact, I’m emotional about that. Anyway, all of this time, my wife was back in Iwakuni in Japan, and later in the year, later in 1950, we moved across to Korea to a place called Pohang, and it was a bare concrete strip with no facilities at all, and we lived in tents. And it was a very frugal existence, and we were resupplied by a transport aircraft coming out of Japan, and I can remember on one sortie out of Pohang where we went up as far as occupied Seoul and the airfield there at Gimpo, and I dropped two bombs on the main runway at Gimpo, and one of those bombs hit the runway and made a big crater. About a week later, the landing at Incheon had occurred, and Gimpo had been retaken, and we flew into Gimpo at night to support a paradrop operation that was being launched at Sunchon and Sukchon, the biggest paratroop operation in the world, I understand. Anyway, this was to cut off enemy troops from … that were trying to retreat towards the north, and I can remember running over a rough patch on the runway, and I thought to myself, “Well, they filled in my bomb crater, and I’ve just run over it.” We spent the night in a bombed-out terminal building at Gimpo. It was absolutely destroyed, and it was the only cover we had and the only place we could spend the night, and the next morning, we supported this big paratroop drop at Sukchon and Sunchon, flying in amongst the paratroopers as they dropped down and giving them support. Now after I’d flown 50 missions, which was towards the end of 1950, I was posted back to Australia and went back to Australia with my wife on a ship out of Kure on what I call Hell Ship Changti, and I have been back to Korea several times, and I’m amazed at the reconstruction of the country. We left it with hardly a building standing anywhere. Anything that stood up was knocked down, and now to go back and see the advances South Korea has made is quite incredible. And a group of us were fated at a ceremony at Chilgok, which was played on TV live, and we were on a stage with garlands of flowers around our necks and hailed as heroes, which was rather … forgotten the word. It was a little unusual for us to be called heroes. Anyway, everywhere we went in Korea, we were hailed as heroes, but I don’t think we deserved that. Anyway, in front of us on this stage, in front of a vast number of people on the side of the river, the Nakdong River there, there was a row of little tables, and on the tables were what we thought were little gift boxes, and we were asked to approach these tables after a while, and in each of these little boxes was some soft clay, and we were asked to make a handprint. We put our hands down on the clay and pushed it into the clay, and when we took our hands away, there was a handprint. Now these were to be the first exhibit in what was to be called the Peace Museum along the Nakdong River, and I’m rather keen to hear whether that museum has progressed and how finalized it is. I would love to go back and see it. Since then, I have had a very unusual Air Force career, becoming a test pilot, flew with the RAF on flight tests of their V bombers and then came back to Australia as chief test pilot for our own Air Force and actually took part in a top-gun competition that squadrons were entered into each year, and two of us became top guns for a year, and I blamed the Korean War for that because we ended up being able to fly very accurately to be able to aim accurately and feel what the aircraft was doing very precisely. I would like to add that my younger brother, name of Keith, Keith Cottee, thought that, “If Milt can do it, so can I,” so he joined the Air Force, and he was trained on No. 6 postwar flying training course. He was posted to Gimpo and flew Meteors out of Gimpo, so two brothers flew in the Korean War. Okay.

>> Well, my name is Kevin Collin Joseph Berriman, commonly known as Col. I joined the Army on the 25th of October 1951, on my 17th birthday, as the Korea War was waging at that time. However, as I was underaged, at 17, you weren’t allowed to go into active service until you were 19. So therefore, the first 2 years of my Army life was spent waiting to go to Korea, in fact. I finally made it just after the Armistice when I went back for a second tour on the line. When we arrived, we did not have to put up with the shelling and the major fighting patrol activity, however, when I arrived my immediate thought was the sympathy for the people, and most of the populous was in starvation at that time. It was a terrible time for the South Korean people. When we arrived, there was still activity up on the DMZ. We established the demarcation zone, and our main activity at the time was patrolling inside the zone, which was allowed in those days. We patrolled one side, and the Chinese, who were still there, patrolled the other side, and we used to to wave to each other occasionally in the center. There was still activity with North Korea crossing the border on several occasions. Of course, we had to keep the whole area fortified, and I served there for approximately 12 months in that activity. There were several clashes on the border at that time, and I was injured during one of them where we had to chase some suspects. We chased them into a mine field. Well, we didn’t ever find out who they … I’ll have to stop. Anyway, we never got to catch the four that we were chasing. We saw them, nearly caught them, but they went into a mine field, and we stopped the chase, but sadly saw them … Well, we couldn’t interview them because there was nothing left of them to interview after that. During the chase, I sadly fell down a ravine, and I didn’t know it at the time, but I’d fractured my spine, and really I was out of action for some weeks after that. I spent time in hospital, and then came back to Korea for a short time where we engaged in more patrol activities, especially along the DMZ. Then my time was up in Korea, and I was hospitalized again, but over in Japan while I was in hospital, I was approached by the public relations officer. They wanted somebody to look after the office in Japan for a while, and they recruited me as a junior noncommissioned officer in the public relations office, where we were engaged in photography of Operation Glory, which was where the exchange of the dead occurred. We were receiving our dead, which had been buried in North Korean graves before the establishment of the static war lines on the Kansas Line on the 38th parallel. And also, we were working returning North Korea and Chinese dead at that time. I was engaged in the fringes of that, mainly working with a photographer that was taking photos of the Operation Glory activities. Some of them are still in the memorial at the present time, when our dead were coming back, and we were sending dead back over to North Korea. I left Japan in July 1955, so I was over there for almost 2 years, and I came back to Australia. Korea had finished with then. I was just due to go over to the mine action, the emergency which was occurring over there, but was found to be, because of my injuries, no longer suitable for the infantry or active service. I retired from the Army in 1957 under the care of our Department of Veteran’s Affairs, who really have cared for me since I was 22 years old. I was re-educated through our Department of Veteran’s Affairs, became an accountant with a university degree and worked with the public service for a further 25 years until my injuries caught up with me again at the age of 48 when I was retired from public work. Since then, I’ve had another career of volunteer work for the ex-service community, mainly in welfare and bereavements, and that’s it.

>> So can you tell us a little bit about how many veterans in Australia are still remaining?

>> Sadly … Can we stop for a moment? You asked me, Hannah, how many veterans are left in Australia. There were 17,850 served in Korea from 1950 until 1956. Now, as of October last year, there were less then 3,000 of us still alive. To be in fact, there was only 2,700. They’re dying very quickly. At the present time, there would be no more than 2,400 of us left. Now, I can also give you some casualty figures of those that we lost. Those that paid the supreme sacrifice during their service in Korea was a total of 356 who lost their lives, 340 before the cease fire on July 1953, and 18 after the uneasy armistice that occurred on that date. Is there anything else that you would like?

>> POWs, missing in action?

>> Missing in action, we still have 42 that are missing in action, about half from pilots that were lost, mostly in the North. Only one that we haven’t recovered in South Korea. The rest of the missing in action are Army personnel mostly in the DMZ, which nobody can find in any case, even to this day. We suspect that some of those pilots that were lost in the North could have gone back on recoveries that have occurred by the Americans. It’s a possibility that they could have some of them in Hawaii. We’re investigating this matter at the present time by organizing a memorandum of understanding with the American authorities. Those that were recovered, of course, are all in the Hawaii cemetery, the beautiful American cemetery in Hawaii. I think it’s called the Punchbowl. Perhaps they could be, but it’s very doubtful if any of the 22 Army personnel are there. They’re mostly still in the demilitarized zone. There’s thousands of Chinese still there, and Americans, many thousands of them, still missing. That’s about all that we can say about the MIAs. Under the current regime in North Korea, I don’t think we’ll ever recover any more of those. Anyway, it’s so long ago now, what, over 60 years. What’s to recover?

>> How about POWs? Australian POWs?

>> POWs, there are very few of them alive now. I can’t tell you the exact … We had probably over 20, 25. Some of them died in captivity, three of them, to my mind. I don’t know whether we have any still alive at the present time. I think there was about less than 30 we had POWs in Australia. What else?

>> What do you think is significant about Australian contribution in the Korean War?

>> What?

>> Australia’s contribution in the Korean War unlike other countries? For example, on top of my head, I could think of is the Australians contributed all the …

>> Well, for our size, we contributed quite a lot, especially … You’ve heard some stories from two of our pilots, both from the Navy and from our own 77 Squadron, who flew there. Our Army contribution, of course, was three infantry battalions, which for our population at that time, 17,850 of us served, so for our small population of seven million was … Our actions, of course, in the infantry we contributed to several major battles: the taking of Maryang-san, which during the static war was … Although we took it in October 1951, it was lost shortly after, unfortunately, but Maryang-san was the main Chinese outpost on the Jamestown Line. That was a major battle. The Battle of Kapyong, of course. Australians and the Canadians held the line at Kapyong during the big Chinese offensive of 1951, in April 1951. The Australian battalion 3 RAR held the Chinese offensive during that time long enough, for 3 days, for them to establish the defenses around Seoul, which stopped the Northern advance. And then, of course, the static war period happened shortly after that in October 1951, where the war stayed until the armistice just about the 38th parallel. For a small force of 17,000, as I said, we lost almost 400 killed in action. Many of us were wounded and injured, like myself, I suppose. I was one of the injured. Anyway, that’s about all I can say really. It was a long time ago. My main thoughts and feelings during the time that I served was heart rending. I was so sad to see the population starving, especially children, which upset me very much as a young man. All that I can say is my … The sacrifice that the South Korea people paid was enormous, and they must be congratulated for how they’ve lifted themselves up after that disastrous time to such a prosperous country that it is today, and I’m very proud to be concerned with the recovery of Korea. They’ve done a wonderful job. That’s about all. I can’t think of anything else. I get bad thoughts when I think of what the people suffered. It was a terrible, terrible time for them. Terrible thing to see. We helped them as much as we could, of course, but we couldn’t feed the whole population. Anyway, that’s it.