>> Hello, everybody. I am back at the Belfast City Hall where the Korean War memorial proudly stands. I am here with the last remaining Korean War veteran, Grandpa Albert. Say, "Hello," and Ms. Carol Walker, who's been extremely instrumental in arranging everything today. She will tell you the story behind this memorial, how it got here and that there is another memorial in Korea, in Seoul, that honors the Irish Korean War veterans. So Ms. Walker ...

>> Hi.

>> Should we do a little ... We're going to loop around and then show you, so I just want to show you ...

>> We just stay here.

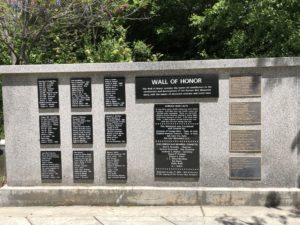

>> ... how it looks like. It honors the Royal Ulster Rifle, and, again, I love this inscription where it says, "The people that walk in darkness have seen the great light," from Isaiah, chapter nine, verse two, and then another ... So there's three sides that honor different ... So we're going to face way because I think this is prettier, so okay. So Ms. Walker, tell us how this memorial got here.

>> Well, this memorial used to be in Korea. The soldiers themselves and [INAUDIBLE] Battle of Happy Valley. Actually ...

>> Speak up.

>> Oh, speak up? At the height of the battle in Happy Valley ... Afterwards, they decided, the commanding officer decided they [INAUDIBLE] something to commemorate the sacrifice of the 157 men that had made this great sacrifice at that particular battle, which as you can see from the memorial, it was on the 3rd and 4th of January 1951, so the padre set out on a task to go and find something, and he managed to come across a Korean stonemason.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> And they were able to get this beautiful pink Korean granite, polished granite, and create a memorial. It was on the field at the site, the battle site at Happy Valley on the 3rd of July in the 1950s, 1953, and at the service, there was a service that took place, and many of the soldiers themselves attended it, and they had the padre at the time, and he performed the sermoning, and the words that are on the memorial that you said, Isaiah, he actually used them as part of the scripture during the service that day and during the sermon, in the remembrance sermoning. Also they laid wreathes at the time, poppy wreaths like Albert has just laid.

>> I do want to show this.

>> They laid these wreaths to commemorate the 150 men that had made that sacrifice and that had died at the Battle of Happy Valley in trying to give Seoul the freedom.

>> Oh, yeah.

>> You can see ...

>> Yes.

>> ... it tells the story.

>> Oh, it tells the story. I didn't realize that before. That's wonderful.

>> But unfortunately, then what happened was after the Royal Ulster Rifles left Korea, there was nobody coming back to visit the memorial, and HMS Belfast, which is actually ironic that it was HMS Belfast, happened to be visiting Korea at the time in the '60s, '64, and it was decided then to bring back the memorial back to Northern Ireland so that the soldiers who were still alive from the Ulster Rifles could still have ceremonies and could attend remembrance services ...

>> That is awesome.

>> ... for their comrades. So it was brought back onboard HMS Belfast. It was brought to the [INAUDIBLE] barracks which was in Ballymena, and it was positioned there. Sadly then, Ballymena actually closed as an army base, and the memorial went into storage for a while, but people like Colonel Charley and Brigadier McCord at the time were instrumental in making sure that the memorial went somewhere important and had the honor that these men had bestowed wasn't forgotten, and the memorial was actually then given this very prominent place here in Belfast, and it has progressed over the years. It's been looked after. As Albert said, you know, there was a new path has been put in. People are able to come here and visit it, and the Ulster Rifles Association will come here and will hold memorial services and still remember the war dead oftentime.

>> I guess I just want to show you that they put up that gate especially for this, you know, walkway because technically, this area right now, there's no pathway. That's the City Hall, and it is in a very prominent location.

>> And it's so close to the cenotaph which is Belfast Cenotaph that's here to commemorate and honor the war dead of the First World War and the Second World War, and so it's still fitting to have it ...

>> Very fitting.

>> ... to have it so close to the cenotaph.

>> So over there, Ms. Walker, pointing out the cenotaph honoring those who died in World Wars I and II, and it's literally ... You can see it from here, and this memorial is right here, and I just wanted to thank you because the one that's filming right now is the daughter of Colonel Charley, who was not only instrumental in getting this here, but in Korea, they now have a memorial honoring the Irish Korean War veterans. It's in Seoul.

>> It's in Seoul at the National Museum, at the museum, because it's a very fitting site. It's where there's also memorials are from the Canadians, and all the other Commonwealth countries have now started as well on the back of what we did and what the Irish did with their memorial, and there's other countries, you know, from the United Nations have placed their memorials that are in a war memorial garden, and it means people can go and commemorate. The good thing is that every year, as well, the Irish, the Irish Embassy, still hold a remembrance service there and for people, so it's not forgotten. [INAUDIBLE] memorial, we spent a lot of time working out [INAUDIBLE], what shape it would look like, how the memorial would come about. It was decided that it wouldn't be a replica that we had here because it needed to reflect as it is today Ireland's [INAUDIBLE].

>> That's true. This was erected in 1951.

>> And the Ireland that we are in today and we were in in 2012 when we started with the project was a very different Ireland. It was an Ireland that had started to come through the the peace ...

>> Aw.

>> ... process.

>> Oh!

>> [INAUDIBLE]

>> Oh!

>> I'm cold!

>> I don't want him to freeze. This is Grandpa Albert, everyone. He's 91 years young, and his memory is impeccable, right? Oh, before we close, see, I wore this rifle green to match him, but can you sing [INAUDIBLE] for us?

[Lyrics]

[INAUDIBLE]

>> Yay! Ninety-one years young. He's the last remaining Korean War veteran in Northern ...

>> Well, one of the ... One of the last.

>> One of the last Northern Ireland ...

>> The last Irish one.

>> Yes.

>> He is.

>> An Irish one. Many have passed just in the past month ...

>> Yeah.

>> Yeah.

>> That's it.

>> ... including Colonel Charley and ...

>> Uh-huh.

>> And many of the veterans that we were able to take back to Korea in 2013, many of them passed very quickly after their trip back ...

>> Yeah.

>> ... when you think about it.

>> So I want to thank you because actually Ms. Walker is part of a different organization and association that remembers and honors those that died in World War I, right?

>> Yes.

>> Yes.

>> World War I and World War II.

>> World War II.

>> And the Korean War as well.

>> Yes. So thank you for bringing the [INAUDIBLE] as well of their memories, and thank you again to Colonel Charley's daughter, yay, Katherine, who is filming this video. So, everybody, thank you so much for joining me in both Ireland, all of Ireland now ... I will be on my way to Wales, so thank you. Thank you. Bye!

>> I think it was either [INAUDIBLE] and we stayed and ate there. Now when we stopped, during the summer months, these people [INAUDIBLE] and the ground [INAUDIBLE] stacked up during the summer to dry, and then at the end of the summer, they bring it in and stack up, say, the houses. Now these would be cottages [INAUDIBLE] and they stack them up. That's the fuel for the whole winter. Now having said that, the same applies in Korea. You know about the [INAUDIBLE]. You know the [INAUDIBLE]?

>> No.

>> [INAUDIBLE] famous thing in Korea, two hands to make a forklift, and the person has a stick with a hook, and when he goes out, he pats it on the ground, and he puts a hook on it and sits there, and he goes around, and gets all sort of stuff, jungle grass or twigs. Anyway, at the end of the day, a pail of stuff, and he'd go back to his cottage, and he'd put all that stuff beside the house. Now that was the winter fuel. Now cooking, they just have the one room, and at the back, they have a kitchen, as you would call it. Now the kitchen comprised of a roof and two sides. The rest was open. Now let's just say the house was [INAUDIBLE]. They have their cooking utensils, like two or three pots, and that was permanent there. That's where they cooked. Now all that stuff is there for the fuel to light the fire and do their cooking. Now I observed this before, seeing what they did, and luckily I had matches, and I got some of the fuel and put it on and lit the fire, and what happened was, the Koreans were very well advanced on the floor heating. Well, as soon as we lit that fire, all the heat went underneath, as well as cooking. It went underneath and heated the floor. Now the floor was big clay again and big clay I say. Holes were there for heat for ages afterwards, and what happened was, the smoke that went out through the back of the chimney, whatever it was, and inside about 1/2 an hour, and it was freezing while were in there, 1/2 an hour. We'd take our jackets off [INAUDIBLE]. It was so primitive but so very good, and that just shows you the ingenuity of the Korean peasants. I'll never forget it. You have your cup, which was aluminium, and you also had what they call a Tommy cooker. A Tommy cooker came in a wee square box of cardboard, and we took this wee metal thing. We [INAUDIBLE] could put either your mess tin ... I don't know whether you know what a mess tin. It's what you cook in, individual cooking. There's two parts, and you do your cooking and that sort of thing on the wee stand with something like if you remember fire lighters to light a fire. Well we had wee small tablets, and they didn't create any flame [INAUDIBLE] just a like a glow, and you cooked your food in that, and that's how you have on the field. Everything was there for you. The Americans' rations was far superior to ours, oh, yeah.

>> How about the cold? Do you remember the cold?

>> Oh, yes, very much so, yeah, mm-hmm, yeah. Not only that, when we went out there, we just had ... It's hard to explain, so you'll need to see pictures. We just had what they call a [INAUDIBLE] a tunic and trousers [INAUDIBLE] sort of thing, and the Americans and all these other things and Canadians, they had their combat suits and their liners inside, if you remember liners. You could zip them out in the summertime and put them back in in the winter. We didn't have that. All we had were ... You'll see a picture of a red coat. We called it a red coat, like a topcoat and your battle dress, and that's all you had, and whenever we got wet, that was just too bad. [INAUDIBLE] in good weather but nothing in the winter. We were ill-equipped, and not only that, but we only had weapons. [INAUDIBLE] was our main weapon, a very good weapon, automatic fire, and then we had a rifle, .303 Lee–Enfield, a very famous weapon, but it was one action. You have quick-fire. You had to keep loading and unloading every time, and you had a magazine of failed rounds on the rifle. No, no, I never had any Korean food.

>> Oh, even now?

>> Oh, I have tried it on the way out to Korea [INAUDIBLE]. I thought it was [INAUDIBLE] asked me, "Well, do you want English or Korean?" So I tried Korean, but it was a bit too complicated. It's too much little tubes of different things to add, but I got through it. Having said that [INAUDIBLE] on the last day of our last visit in May there, I forget the name of the [INAUDIBLE]. As I recall, it was a woman, and she had a seven course meal for us on the [INAUDIBLE] before departure and through seven courses, and you would hardly see what was on the plate, and it was very good. It was different what I got on the aircraft.

>> Korean food at the time, but did you try Korean liquor at the time?

>> No, the only thing we got was two battles a day of Asahi, Japanese beer.

>> Oh.

>> But having said that [INAUDIBLE] as it seems a terrible ship. You had a hole in the wall, just like the hole, square hole, a square in the wall, and you were issued out two bottles of Asahi beer. That's what we got.

>> Oh, I would have never guessed that. So no soju, huh, no Korean alcohol?

>> No, no, it was all Asahi beer.

>> Oh, okay. Do you think you'll see a unified Korea in your lifetime?

>> It's hard to see. I would like to see it. I would definitely like to see it because it's a [INAUDIBLE] having the knowledge of what has went on there, the starvation. Even the soldiers not being able to get [INAUDIBLE] and the feeling of the children and all those big pompous parades with their machinery and rockets and what have you. It's a terrible site.

>> Well, I'm hoping for peace not only on the Korean peninsula but in all of Ireland as well.

>> Uh-huh, thank you very much. Ten o'clock, 22 hundred hours, and what happened was, as we were going out [INAUDIBLE] and we're going across, and I remember going up this hill here, and I went in the dark and the windscreen I could see ... Sorry. It was heavy gunfire, consolidated gunfire, and you see the tracer bullets on the reflection of my windscreen, and I said to the guy who was with me, "This is good." [INAUDIBLE] our tanks, centurion tanks, and I said to the guy with me, "This is good. They're giving us covering fire to get out." What happened was, I found out later that the medical officer and his driver [INAUDIBLE] was quite some distance behind me. Apparently the Chinese had did a horseshoe movement. Instead of coming across, they came that way, a horseshoe movement, and closed it, and the people behind me, that was them trapped and taken prisoner of war. I'll never forget that. I'm surprised you don't know about the

[INAUDIBLE] is famous.

>> ... the door who had been captured and could walk over the UN forces with them, but the UN troops, the Astor Rifles and the others who were with them, who had been killed were just left to lie, and they weren't buried by the cruiser, and they went out, and in this hard, harsh ground, they buried the bodies because they felt they needed to give respect to these people from overseas who'd come to fight for them, so it was very poignant, and then we were told how after the ... What we were shown were the ... Albert showed a picture earlier of the bullet holes on the bridge, which another Astor Rifleman ... I think it was a lieutenant then, Merv McCordy, went on to become a brigadier eventually. He got an MC, a Military Cross. Himself and somebody else protected a sort of area and ... two of those who had died in Korea, and they ... I discovered when I was back recently in Korea that near that side of Seoul is where all the monumental memorial makers were, and so that's how they managed to find ...

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> Yeah. The Padre found ... was told to go and get a stone, and he found a stonemason as well. Apparently, they were in the back of an army truck. I assume he was paid, and they drove around with the ... wherever the battalion was going, and he was told to carve on this memorial to remember the Royal Astor Rifles and the others who'd been there and then in Happy Valley and who'd died there and others of the Regiment, who'd died nearby or elsewhere in battles that included Imjin because the Astor Rifles had heavy casualties at Imjin as well, and that was dedicated July 1951. My dad wasn't there because at that stage he was in Japan training people to go to Korea and things, so he wasn't there but some very famous, very poignant pictures of that. That memorial, we will see later. It came back to Northern Ireland in the 1960s, put up in Palace Barracks ... not Palace Barracks, sorry, the barracks by Mina where the Regiment, the Astor Rifles, had their depot, and then that closed in 2010, and it got moved to outside the city fort here in Belfast, and my father, Merv McCordy got the MC in career, and a lot of the others of the Regiment were very instrumental and moving in that getting it placed outside the city hall, and it's been recently refurbished, and we've now got access to it from the Cenotaph area, the city hall, and they're looking after it well. So my dad and I went back to Korea in 2011. Mr. Kim showed us around Happy Valley, and my dad, I think he never totally said this, but I think, to me, but I think he always felt guilty that he'd survived, and so many hadn't, and he really wanted to do something to remember those who'd died in Korea of the Regiment, and initially we were thinking about putting up a wee plaque or something in Happy Valley. We spoke to the British Ambassador when we were there. We spoke to Mr. Parker when we were there. When we came back, we spoke to members of the Regiment because obviously it would have to have regimental approval, and then when we were sort of just ... We were just thinking of doing something quite small, really, maybe in Happy Valley itself, and then I got ... We met Andrew Salmon out there. He'd already met my father. He'd been to Belfast 2 or 3 years before to interview my dad for his book, "To the Last Round." He interviewed quite a lot of the Royal Astor Rifles for that, and he was delighted to see my father in Korea. They got on very, very well. They enjoyed going out and both good storytellers, so they could sit around and drink and tell stories, top teacher, he was, with the stories. But anyway, Andrew Salmon sent me an e-mail and said that the Irish Association of Korea and the Irish Embassy in Korea were thinking of putting up a memorial in Korea to those from Ireland who had died in the Korean War, and because although Ireland wasn't a UN nation, it ... People from Ireland had thought and for the Americans, the Australians, and then many of people from the south of Ireland were part of the Royal Astor Rifles, which was a British Army Regiment, so it was part of the UN. So and they were also wanted to remember some Padre, some missionaries who died in Korea as well, and there's a link there with the Royal Astor Rifles too, which I'll explain in a wee minute. So anyway, we then started liaising with Ambassador McKee, and again, we had to get approval from the Regiment and from the British-Korean Veterans Association, and there were links between Dublin and Belfast and everything else because obviously, we have these politics involved in this country too, and in among that, that's when Mrs. Carol Walker came on board because my mother used to ... my mother? My father used to be ... He was very much behind the setting up the Somme Association, the Somme Museum to remember those of the First World War from the north and south who'd died at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, and he knew that Carol had a lot of experience in memorials. She put up memorials for the First World War in France, in Turkey, in visitors places. I'd asked her initially for advice on that, and then discussion began about taking back veterans from the Royal Astor Rifles and from Ireland. Generally, Carol has had experience of taking back First World War veterans to First World War battlefields, and so that's how she become involved in the ... on the team, basically, and then a representative of the Royal Irish Regiment, the modern regiment for the Royal Astor Rifles, which the Astor Rifles, my dad's regiment in 1968 amalgamated with three other regiments into the Royal Irish Rangers, and then in 1992, that became the Royal Irish Regiment, and they're very supportive of their heritage and interested in their heritage. So lots of discussions about the memorial, lots of liaisons between Korea and Ireland and phone calls at 7 o'clock in the morning and to work with the time difference, and then in 2012, Carol, myself and Trevor Ross, who was representing the Royal Irish Regiment, went out to Korea at the time of the Commonwealth Veterans revisit the following year and met with the British Ambassador, the Irish Ambassador, members of the MPVA in Korea, went to see possible memorial sites, and it was then that it was decided the memorial should ... the key memorial should go up in Seoul because it'd be easier to look after it there by the War Museum and things, and the Irish Embassy said it was look after it and that there would be a panel put up in Happy Valley as well to remember the battle in Happy Valley too. 2013, and you'll hear more about this from Mrs. Carol Walker, the memorial was dedicated in Seoul. My father and I were meant to go to be there for that dedication and for all the other events and be there with the other veterans from the Royal Astor Rifles and from Ireland. Unfortunately, my mother had a very severe stroke just a week or two prior to us going out, and we, anyway, my father and I couldn't go. She died shortly after the veterans returned from Korea, but we were very close in contact with what was going on. My dad was very keen to know. He kept saying, "Have you had a signal from Carol?" because he's not quite into e-mails, but a signal, and so Carol, Trevor and the others sent back information of what was going on, sent photographs of the memorial being dedicated, being put up and everything, but me and my father were ... My father and I were very evolved with Carol and others, and everything had to be approved with the wording on the memorial and everything else. Then with regards to the memorial, my dad ... One of the sides of the memorial, one of the sides is the Royal Astor Rifles and reflects this memorial here in Belfast and the wording on the memorial here in Belfast, and it particularly mentions Happy Valley. Another side mentions those Irish birth and heritage. Another side is ... talks about seven missionaries from Ireland, who died in Korea, and one of those missionaries, my father actually knew. Father ... I think he's known as Father John O'Kane, is it?

>> It's O'Kane.

>> Yeah. Father John O'Kane, though, my father knew him as Father Jack. Quite often in Ireland, people who are called John are known as Jack, very confusing. Anyway, so my father knew Father Jack. He'd been a Royal Astor Rifles Padre in the Second World War. We think he might have been at D-Day with them, but we definitely know he was with the Royal Astor Rifles in the Second World War. He was older than my father, maybe 10 years older than my father, and then after the war, my dad was in Palestine and Egypt, and he was the Catholic Padre with the Regiment there. The Royal Astor Rifles has a Catholic Padre and a Protestant Padre, and he was Catholic Padre in Egypt, and he remembered him because he was a Padre. He was part of the officers' mess. He had a tent, himself, I think, because he's a Padre ... had his own tent because my father had to share a tent with somebody else, which are all the boys who are over there, had a lot more in the tents, and he remembers them being very good at cards. He remembers them being a lot of fun. He remembers them riding around the camp on a motor bike, and all the guys thought he was wonderful, so my father was very sad when he'd heard that he'd been killed in Korea. He knew he'd gone out to Korea as a missionary, and so that's a link between the Astor Rifles and the others in the memorial as well. Then in 2015, this ... the ...

>> My name is Adrid Fieren. I am a man of 85 years old. I served in the Korean War with NORMASH in '52, '53. NORMASH was Norwegian contribution among the nations that helped South Korea to defeat the North Korean War from North Koreans. NORMASH is a mobile army surgical hospital. The main purpose for NORMASH is to take care of soldiers directly from the front line, wounded which has to be X-rayed and to be operated by surgeons. NORMASH therefore was placed approximately 10, 12 kilometers from the [INAUDIBLE] front line. We were a part of 8th Army and had, as far as I remember, three divisions to serve soldiers from. Soldiers coming into NORMASH was treated there and had to leave before the 3 days. Then the patients had to [INAUDIBLE] other hospitals. NORMASH was served by, I think, approximately 600 people from Norway. Each continent each period of 6 months, and then 106 persons on each period. I was in the guard, controlling all together with then all the Norwegians, and our duty was to guard camp to serve the borders. What do you call it [INAUDIBLE]?

>> Barbed wire.

>> Hmm?

>> Barbed wire.

>> Barbed.

>> Wire.

>> Wire but [INAUDIBLE] to be in the main gate all 24 hours. Together with [INAUDIBLE] Korean soldiers, a soldier from ROK Army. AMASH, the main thing in AMASH is of course the hospital itself, but it has many service functions around [INAUDIBLE] transport service in the camp, guarding and so on, and we had, I think it was approximately 30, 40 ROK Army Koreans [INAUDIBLE] guarding people. I think there were approximately 15, 20 and [INAUDIBLE] to maintain the camp itself. Then the nights especially in the guard, we were two then, one Korean and one Norwegian. We had difficulties, of course, with language, but we tried to communicate a little. But one thing we learned each other, that was a song. The Korean has a folk song called [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] and the Korean colleague on guard, the Korean learned us [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] and we learned him [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] a Norwegian folk song, and the [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] we learned goes like this. [Lyrics] [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]. A little like that, we learned, and perhaps in Korea, an old man of 80, perhaps he's singing [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] maybe. Why did I go to Korea? Well, I was already 20 years old. I had finished first military service in regularly in Norway, and we were all volunteers, and on that time, I nearly didn't know where Korea was, but I had to look up on a map and find the little country called Korea, but it was the adventures, one thing, to travel all around and half around the world. I'd never been in plane before. I'd never slept in a hotel before. It was new adventures waiting, maybe a little to take part in a battle against communism, but I wouldn't say that was the main thing for a young man on that. However, it turned to be a very fine trip. Six months after the War, Korea is one of ... We used to say that no other country in the world is so clever to say, "thank you," [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] as ... You know [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]? Norwegian ... as the Korean. I am so happy that I have been four times back on revisit trips.

>> Show us that picture where you went to Korea and that story of the nurse and the patient.

>> Yes, that's a good story. You see here we have a book which we, the veterans in Norway, has made possible, and it is also translated to Korean, and here, I can show you one picture. No, it's not here. It's in the magazine from one of the revisit. This was celebrating the 60 years of peace.

>> Armistice.

>> Huh?

>> Armistice.

>> Armistice, yes. It's not peace yet. There we had a nurse who served in the very first continent in '51, and she was taking part in that trip and [INAUDIBLE]. You see this? That's a lady. Her name is Gerd Semb. She is now a lady of 95, I think. When we someplace on that trip, I think it was in Uijeongbu, we had a lunch there, and when finished her lunch, going out, there came a man, this man to Gerd and saying, "Ah, I must thank you. I was young man, and I had destroyed my face, and you treated me." After more than 60 years, it seems this happening. That was a very funny and a very good story.

>> You're on the cover of the magazine.

>> Yeah, this is the magazine for the Norwegian forces.

>> With Gerd.

>> Yeah [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] is the name of this.

>> Who are the other two ...

>> Here is also the lady there, yes.

>> And who is the other lady?

>> And if it is of interest, this is me, and this is the Minister of Defense in Norway at that time. She also followed this trip.

>> So what did you think about Korea?

>> Now or on that time? At that time, Korea was more or less a ruin. In the place where we were situated, the battles had gone four times through, so it was no houses, no buildings, all destroyed. The people who were there lived in houses built of soil and equipment they held after the battle. Especially fort making ceilings on their houses, they took boxes of beer and open it so it was more like this. If you took the bottom and the top of a box of beer, you will have a flat metal, and many of those was how they built the ceilings, top of the ...

>> Roof.

>> ... roof, yes. Nowadays, Korea, the first time I visited was in '84, I think. It was a new modern country. It was unbelievable for me to come back and see this wonder, and the Korean people, I love them. I really love them.

>> Number one.

>> Number one, they are number one.

>> That's number one.

>> And we have been so happy. We have this veteran association to have a very, very good connection with the Korean ambassador. He is number one. So I think me and all the other Korean veterans also are very fond of the Korean people.

>> Well, we thank you.

>> Thank you.

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE].

>> Enough.

>> My name is Fillmore Kent, and I am 85 years old, and I served in Korea from November '53 until November '54. That was the last two continents in NORMASH history. I volunteered, as everybody who served in Korea. The reason why the Norwegian, Trygve Lie, was the first general secretary of UN starting in 1946, and it was very much publicity around the Korean War in Norway at that time. So, of course, I wanted to help. Also, it was an exciting because you cannot imagine today how far away Korea and Norway was. The second reason, or the third reason, was that I needed money to start my study in Germany, and the salary was partly paid in Korea and partly in Norway so you can save. We all had 6-month contract. I renewed my contract after 6 months, and that's the reason why I spent 1 year in Korea. The reason why I was picked out was that I had some first aid courses in Red Cross, and I was already a laboratory man, so I first picked out to serve at the hospital laboratory. When I came down, the position was occupied, so they put me as assistant to the operation tent. It was quite a new experience for me, but I learned rather quickly, and you get used to it. It was after the armistice, but we still had very many military patients but gradually fewer army people and more Korean civilians. After the 6 months, we had the opportunity to travel down to the hospital in Busan, the Swedish hospital, permanent hospital, so we get to know very much some Swedes. We had also very good relations with the Koreans in the camp. We were close friends. I have a theory in that aspect, Korea is a rather small country dominated by China and Japan. Norway is also a small country, dominated for centuries by the Danes. Norway was just a farmer's country with no education. If you wanted to have education, you had to go to Copenhagen. Later, we were under the strong influence by the Swedes, so my theory is that Korea and Norway have more or less the same history, even though they are opposites of the world. In April '54, NORMASH also engaged six Korean nurses already educated to help out because of the many Korean civilians, and I got to know one of them, and she came to Norway in '57 for further education and to meet me. We married in '61. We are still married. We have three children and eight grandchildren. So for me, the Korean event influenced my whole life afterwards. My wife is really happy because it's very important for Koreans to have a family and some success, so she's quite satisfied in her life also.

>> I would love to see her picture. I would love to see her picture.

>> I not here.

>> Oh, wow. Fascinating. You went back to Korea, you said, for a visit, right?

>> Yes.

>> How many times?

>> Yes. I think after ... These are the 30 years after the armistice. Koreans started the revisit tours, and I have been in Korea twice, in '83, so after 30 years, and in 2010. It was very surprising to get to come there and see that the fort is still ready to shoot after 30 years of armistice.

>> Even now?

>> Even now. But I mentioned the Busan hospital Swedes. As I told you, we got along, Swedes, very good, and they were both countries who had commission in Tongduchon to secure the armistice, and they still are there, I suppose, so we could visit them very early in 1954. I'm also a board member of the Korean War Veterans Association in Norway, and we have two events yearly here at the memorial statue. In June, the military attache located in Stockholm comes to pay tribute to our dead, and in the second Friday of November, we have our annual meeting.

>> Don't touch that. With your hands, don't ...

>> Oh. Oh. Okay. Sorry.

>> Okay. Say that again about your Association reunions.

>> Huh?

>> About your reunions. Say it again. You have two ...

>> Yeah. Okay. I'll start from the ... Yeah. Okay. Mm-hmm.

>> [INAUDIBLE]

>> Now, the Korean Veterans Association have two occasions to remember the dead ones here at Akershus Castle. The first one is in June. The military attache for Sweden and Norway located in Stockholm, he comes to pay tribute. And also the second Friday in November, we have our annual meeting where we also have a ceremony at the statue, and our president [INAUDIBLE], he is a former officer in the king's guard, and he takes care of the ceremony with flags, with armed guards and military band. So it's a rather great experience for us.

>> Do a lot of people come?

>> Yes, because in our association, we also have members who served at the Scandinavian hospital in Seoul, which was created in '56 or something, so they who served there also are members of our association.

>> Do Korean Norwegians come, too?

>> Yes, of course, the embassy and the embassy staff and some Koreans, too.

>> How about young people?

>> Not so many young people, but my experience is that young people in Korea, they know very much about the Korean War.

>> More than other countries.

>> Yeah.

>> Well, what do you think, because the Korean War is called, "The Forgotten War"? The Korean War, they say, is "The Forgotten War."

>> Mm-hmm. Not for me.

>> Hm. You're right. So I'm hoping to preserve this history for young people, younger generations. I'm very glad that Julie is here because she is young Norwegian, and I want more young Norwegians to be proud of your service.

>> I can also mention that from 2010, Korea also invited grandchildren of veterans. So in the first tour, we had 12 participants from Norway [INAUDIBLE] from Norway, and they had 1 week in Seoul and Busan and 1 week marching along the line, so it was a really good experience for them.

>> Did your grandchildren go?

>> Yes. I had one grandchildren. Actually, I had two grandchildren now, and when I revisited Korea in 2010, I brought also another grandchildren with me, and [INAUDIBLE] grandchildren and also Lucy [INAUDIBLE] on Saturday if she had the grandchildren.

>> What did they think?

>> They were very happy, and of course, it was a great experience for the grandchildren, too.

>> I'm sure they were very proud of you. I think so, right? Because they see Korea now, right? What do you think of Korea now?

>> Now, as I already said, the frontline passed four times through Seoul, so it was nothing left when we arrived, so it's amazing how the Koreans can manage. They are very clever and very grateful, work very hard.

>> Yeah. We do work hard, and we're very grateful people.

>> Yeah.

>> We are very, very thankful.

>> Yeah. Mm-hmm.

>> We don't forget.

>> No, and of course, if you look to North Korea, you understand why you are grateful.

>> Yes. I say that I am very, very fortunate and blessed that I was not born in North Korea, you know?

>> Yeah.

>> So I hope that, you know, you went, and you defended South Korea's freedom, right? I hope that the war will end soon and Korea would finally have peace and reunification so that North Koreans can also enjoy freedom. Do you think that's possible?

>> Doesn't look that way. And, of course, Germany was divided in the same way, and it ended, but you can still see a difference between West Germany and East Germany, even in Berlin. So it's not easy to combine West Germany and East Germany, still some problems, and I suppose in Korea, it must be even more problems. But of course, I will wish you good luck.

>> Yeah. I hope so, too. Anything you would like to say to maybe young people all around the world about war, peace, about your experience in Korea?

>> No. I don't think so.

>> No? Well, thank you so much for your time.

>> Okay. Okay.

>> You have from there, the German, Norwegian soldiers in Germany after war.

>> Okay.

>> And we have those from Sweden, if you see, to Sweden, the Korean, Norwegian Korean there in the middle.

>> Okay.

>> [INAUDIBLE].

>> Do you read Korean?

>> Yes.

>> Yes.

>> NORMASH, 1951 to 1954, wow, 623 Norwegian ... More than 90 patients.

>> Ninety thousand, 90,000.

>> Ninety thousand, I mean, 90,000. Were any Norwegian servicemen or women killed?

>> Three of them.

>> Not in battle, not in battle.

>> Three?

>> But not in battle but in service.

>> Accidents.

>> Accidents?

>> Yeah.

>> What kind of accidents?

>> Driving accidents.

>> Driving ...

>> In Korea?

>> Yeah, yeah, during the service, yeah.

>> Oh, no.

>> And the third one is a Norwegian sailor.

>> Sailor, yes.

>> Because when the Korean War started, a lot of Norwegian ships were in the area, so they worked with evacuation of civilians from the war zone and also the transportation of heavy military material from the fan to Korea and back to Japan for repair also.

>> So ...

>> But it's not so well-known.

>> I only thought ...

>> We have written about it in our book.

>> I only thought doctors and nurses went from Norway.

>> Oh, no, personnel too. To run a MASH, you need more than doctors.

>> One hundred persons in total.

>> One hundred and six.

>> Sixty of them working in the hospital.

>> Each continent, 106 persons.

>> And the very necessary addition ...

>> Cooks, cooks, guards.

>> Drivers.

>> Drivers.

>> Technical personnel.

>> Technical and camp workers.

>> But ...

>> And in addition, 60 Korean too.

>> Yes.

>> Really? So ...

>> About 25 Korean guards?

>> Yeah, approximately.

>> Approximately.

>> And four were working in the camp.

>> And civilians too.

>> So 100 medical personnel?

>> Yeah, yeah, and the MASH consists of 100 persons, Norwegian persons.

>> And 523 other servicemen from Norway because there were 623 total.

>> Yes, in total.

>> No.

>> All Norwegian were volunteers.

>> Each continent ...

>> Yeah, continent, yeah.

>> ... for 1/2 a year, and we had six continents.

>> Seven, seven.

>> Seven at all, and they changed every 6 months, and each continent had 106 persons, personnel, and of those, approximately 40 medicals.

>> No, 60 medicals.

>> So many?

>> Yeah [INAUDIBLE].

>> [INAUDIBLE].

>> It doesn't matter, doesn't matter.

>> And of course, the medicals, the hospital is the main thing of a MASH, of course. MASH stands for Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, MASH.

>> There's a very famous TV series in America.

>> We have seen that.

>> Comics.

>> What do you think of that?

>> The scenery is very natural. I don't know where it's taken, but it looks like Korean scenery.

>> Yeah.

>> And the tents and everything is very, very close to ...

>> Real?

>> ... real, yeah.

>> And you see here, NOR, that stands for Norway, MASH.

>> And if you behaved well, you could have a new contract for 6 months. I behaved very well, so I stayed for 1 year.

>> One year, but why ...

>> He didn't behave so well, and so he stayed for another 6 months.

>> You all volunteered.

>> Yes, we all were.

>> Everybody was volunteer.

>> Wasn't it difficult? Why did you want to stay longer? Wasn't it difficult?

>> To stay longer? No, no, I had service after the war or armistice.

>> Approximately 100 stayed more than ...

>> Yeah.

>> ... 1 year.

>> Yeah.

>> Six months, 1 year at all. It was a good pay, you see, after Norwegian conditions, and so it was ...

>> To be honest, I had three reasons for going to Korea. First of all, Norwegian Trygve Lie was the first general secretary of United Nations. He was well-known internationally because Norway had a foreign administration in London during the war, and so it was very much first about Korea and the Korean War. Of course, I wanted to help. Secondly, it was very exciting, so exotic.

>> Yeah.

>> You cannot imagine today how far it was from Norway to Korea and how different the societies were, so it was excitement, and thirdly, I needed money for my study, and we were not so very good paid, but most of the money was in Norway.

>> Yeah, yeah, yes.

>> And we had a small salary.

>> Scrips.

>> Yeah, scrips.

>> Money valued only during war, Korea.

>> Yeah, and the scrips started all in first World War, I read once.

>> Yeah, special money.

>> Yeah.

>> Well, I am Mr. Maximo Young, 94 years old. Well, my war experience started with ... I was working with a company in the Philippines. That was 1941. Later on, I was sent to States to study agriculture, and then from there, I was one of those chosen to select members of the group that our government committed to be sent to Korea. That was 1950. Now initially, before we were sent to Korea, after selecting different members to compose the 10th Battalion Combat Team, we had some training. Our training ended sometime on September, so on September 15, we made our first trip to Korea aboard [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]. We left the Philippines September 15 and arrive at Korea 19 September. Upon arrival at Korea, we could see the whole area, stationed in Pusan where we landed. There were all of us armed for war. It was this time when the North Koreans invaded South Korea on 15 September the same year. So upon arrival at Pusan, our initial debarkation area, we were sent to [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] for a probation period. From there, we stayed for overnight, and then the following days, we were sent further north to acclimate ourself with the area, including the weather. The weather is very different. It started while in Korea. It was always frigid, very cold. We stayed there for almost 15 days. From there on, we were attached to a US division, the 3rd Army Division of the US. From there, we were assigned an area that is south of Seoul, extending up to about 15 kilometers north of the 38th parallel. We were assigned to patrol an area which is the main line of supply used by the United Nations coming to transport men, soldiers and supplies to the front line. Now it was an incident where our group was designated to secure a certain area not to be a North Korean area. So November 11, we were sent to patrol the area to find out whether there are some North Koreans who are disturbing our supply road. Sometimes they're ambushing friendly troops and sometimes destroying vehicles that are a part of the group that fights the North Koreans. So on November 11, I was in charge of a group to reconnect the area going north. We were the first group to more or less move to reconnect the area. With us were some segments of two companies and some medical units and some support units. Now at 7:30, we left the area from somewhere in south of Korea, going to Yujeong, but our designation was to look for the enemy somewhere at [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]. Along the way, our head group encountered a land mine. The land mine exploded, and all the Jeep which they were riding exploded and flew over, and two of our men were disabled, but we continued moving forward to [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]. Now after completing a bend, going to [FOREIGN LANGUAGE], and an area which is more or less a distance from a hill, a hilly place, we encountered simultaneous burst of enemy fire suspected to be about of 4,000 deployed along that area. We were just little found out that place where we passed after were 45 areas in preparation for any ambush for any enemy that goes north. So since it was surprise attack, all of us would lie down, and then most of our men, cadet or not, because it was a very ideal place for ambush. It was river down the road, and the enemies were all deployed up on top the area. So after several bursts of fires, my men, our men, cannot move, so I was a commander of five towns. I was the fourth town. After a lull, I patrol the periscope. Anytime you have a periscope, you can see the area around you through a telescope without being exposed. I look left and right, and I found out not a single man what belongs to my group. We were about 90 to 100. All of them were flattened to the ground in that group. So as idea forward looking at the enemy, I saw some of them already more or less conferring to each other on the left side and off on the right side. Thinking on my officer [INAUDIBLE], I know they're ready to attack because nobody could fire. So what I did: I opened my tank. A tank, it has a cover. I open the hatch and went out and manned the machine gun with this part of the armament of the tank. What I did is, I cracked the .50-caliber machine gun and started firing from the left. As I continue firing, I saw some of them tumbling down, running, some of them getting out of their trenches. I swing the machine gun from left to right, aiming at those people who already were trying to plan an attack against us. I continue firing. I split about two boxes of ammunition until later on, the support fire coming from behind from our artillery. Now when I started firing, running after this soldiers who were getting out of their trenches from left to right, and after about 15 minutes, there was a support fire from behind. So after about 15 minutes, our soldiers started advancing, returning the fire. Incidentally, after that, we were able to more or less get them to surrender. After a head count, there were about 42 dead and about 201 dead. From there, we straight to [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] to complete our mission. That is the first time that we encountered the North Koreans from the Filipino side is the first time we encountered these North Koreans. Now after the incident, I found out there are foreigners from other countries who also belong to the United Nations command, went down to congratulate me for what I have done because without the fire, I think all of us would have been as good as dead because we can not know. Just imagine an area where all of them, you have the commanding view of the area, and all of us were down there like the pigs that are being shot at. That was the first incident I have encountered. That was the first incident where the Philippine forces encountered the North Koreans, and that was the first victory of the Philippine army.

>> What year was that? What month and year was that?

>> That was 1950, 1950.

>> '50, what month?

>> '50.

>> What month, month?

>> Oh, November.

>> That was during the most difficult battles.

>> Yeah, that was the most difficult.

>> November 1950.

>> Then from there, we went north, fought there, and then from there we found out that most of those ... There were 40,000 North Koreans stationed at the area. Now when we went there, all of them dispersed because of our combined attack. Aside from us, there were support units and some planes of the Allied that supported us.

>> Well, as Vice President of the Filipinos Korean War Veterans Association, what are some of the activities that you do as an association, and what do you think is important for people to know about Filipinos who fought in the Korean War?

>> Well, you're asking me about the different activities we did?

>> What's important about Filipinos in the Korean War? What's special about Filipinos? For example, Turkish soldiers, they never left the dead. You know?

>> Yeah.

>> So every country, there's something special about that country. So what would you say that you want people to know about Filipinos who fought in the Korean War? Like Thai, they were called Little Tiger. Yes. Something about Filipinos?

>> Well, the Filipinos, when we arrived at the Korea, we found that most of the civilians that they're fleeing because most of those Koreans, they are uneducated. That's partially the reason why the Japanese, when they occupied Korea, they prohibited Koreans to study, so more or less, never educated them. So during the time, whenever attack, they can not do anything. And what were we observed in Korea were civilians, they don't know where to go. Children, plenty of children, the children were left alone. They were alone. They had nothing, nothing to eat, especially the families.

>> So what's special about the Filipinos?

>> Well, what's special about the Filipinos?

>> Mm-hmm. Yeah.

[ Chatter ]

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]. What was your role? What was your role that made the presence of the Filipino contingent, critical because of the war or important to the war? [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

[ Chatter ]

>> A significant contribution.

[ Chatter ]

>> Well, first, more or less, fighting against the Koreans and then helping the civilians who are in need of food and protection, security.

>> I know Filipinos went to Korea even after the armistice, the 5th Battalion, right, went after, and it helped rebuild Korea.

>> Yeah.

>> Maybe that's a very significant contribution in the war that ... Many other nations, they left, but Filipinos, even after, they sent another battalion to help reconstruct. I think that's very significant.

>> Well, the contribution that was assigned to the Philippines after the fight, they were there to, more or less, study the nuclear activities of ... Well, the Americans told them something nuclear, more or less expecting the world will continue, but incidentally, there was an armistice that lured about 1953 where they declared ... They stabilized rations.

>> And I know there were 41 POWs, right?

>> I have the number. Excuse me. As a result, we have 112 killed in action, 112 killed in action, and then missing in action, we have 229. And then ... wounded in action, I mean. Missing in action is 16, and we have 41 POWs, prisoners of war. Now the 41 prisoners of war, after the war, we tried to verify, follow up, their destinations. Of the 41, we were able to locate, I think, 36, 36, 36, and until now, the remaining numbers are not found.

>> Really? Five of them are not found?

>> Until now.

>> Wow.

>> We suspected that they had died, and they were never found.

>> Recovered the remains?

>> Now, for the POWs, we have 41. I think 6 of them are not also accounted for. The others have gone back to the Philippines. After 3 years there was ... After the armistice, there was an exchange of prisoners, and some of them came back.

>> But not all?

>> Yeah, yeah, yeah.

>> Oh, no. The families of the POWs that never came back, so they're just waiting?

>> For your information, the total number of Filipinos that participated in the Korean War was 4,720.

>> Four thousand seven hundred twenty?

>> Four thousand seven hundred ...

>> No, I thought it was 7,200.

[ Chatter ]

>> I thought it was 7,200.

>> Oh, no. I'm sorry. Seven thousand four hundred twenty.

>> Yes. Yeah, and now in the association there are about 3,000, right, left in the association?

>> No. As of last June, I could account for 1,700.

>> Oh, that's it, huh? One thousand seven hundred.

>> One thousand seven hundred living.

>> Living.

>> Living. And the others, out of the 7,420, the others that came back was assigned to different places, and we have no means of contacting them. Now out of that number, as of now, our living veterans, verified living, is about 34 living veterans.

>> Thirty-four?

>> Yeah, thirty-four.

>> Thirty-four?

>> Thirty-four, yeah.

>> I thought you said 1,000 ...

>> That is for the Tampa City, for the Tampa City.

[ Chatter ]

>> Because there was five visitors when the ... The 10th was about ...

>> The 1st battalion that went.

>> Yeah, that's right, battalion.

>> Yes, yes.

>> The 1st battalion ...

>> There was only 34.

>> Yeah, 34.

>> And you're part of the 1st battalion.

>> Yeah, the very 1st battalion.

>> The 1st battalion are the oldest, right. I heard there's a 101-year-old veteran. One hundred and one, is he the oldest?

>> That 100-plus ... Most of the casualties were of the [INAUDIBLE] were because of another battle that was a year long. That year-long battle started way back in April 1952. That was the time the North Koreans tried to post in order to invade the South Korean.

>> Wow. One last question, have you been back to Korea?

>> Yes, five times.

>> Wow. Five times.

>> My son, he went there last year when it was awarded the highest spirit medal in South Korea. In fact, I will give you a copy of ...

>> A citation.

>> ... a letter. I wanted to take the award, for sure.

>> What did you think about when you first went to Korea? How did you feel?

>> Well, I was single dad during the time, and I was one of the selected because I came from Fort Knox to study the armored veteran. When I went to Korea, I never thought I would be coming back because it was the time when the North Koreans were very forceful in trying to invade South Korea. Now my impression about South Korea when I was there, it was a place where people are very poor. They were very, very poor. You could see them trying to get food from us, and mostly is what I said, most of the people there are uneducated, very poor, and they have no means of life except farming.

>> But now ...

>> Wow, terrible. The are the best shipbuilders.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> In fact, they intended to open up four shipyards in the Philippines so that they will continue to build ships because shipments is a problem. You can transport anything. Back then, it was very costly. Unlimited, but shipbuilding, I think that is what the ambassador told us one time when he said, it was 3 years ago, the ambassador of South Korea, we were having a meeting. The intention of South Korea is situate that the Philippines, which is very, very poor now compared to 1950. We were the second best country, but after the World War II, everything was destroyed including our factories, our everything. Now what the ambassador told me before was that the intention of the moment of South Korea was that within 30 years they want the economy of the Philippines to be in power with Korea. In other words, they will support the Philippines' infrastructure, agriculture, everything, so that way, 30 years, that was 2013. He said 30 years, that was the intention of South Korea. Thirty years from that time, they want the economy of the Philippines to be in power with South Korea.

>> I know. I visited too many countries, and when I went to the memorial today, I was amazed, and I said it's the best memorial and museum that I've ever seen in any other country. You know?

>> Yeah.

>> The facility, the Pepco facility?

>> Yeah, yeah, yeah.

>> It is amazing.

>> Very amazing.

[ Chatter ]

>> I was so impressed. It's maintained beautifully. The museum is very nicely presented and display. The auditorium, the memorial ...

>> Yes, yes. Way back 800, I think.

>> Just so wonderful, and I'm very proud to know that the Korean government has been able to build that to honor and thank the veterans. So I was very proud to hear that. I hope that you are very proud when you went to Korea recently to see skyscrapers, Hyundai, Samsung, LG. Korea is very prosperous, and Koreans are successful because of your sacrifice. Yeah.

>> Well, there is a way they have best fusion because the North Koreans has not gone down to South to destroy. They have a very big space.

>> I am Robert Jupar Domingez. [INAUDIBLE]. I served in military service in 1950 after graduating from the high school. I missed a [INAUDIBLE] in the military service. Then when the war broke out in Korea, it was 1950. I volunteered. [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]. I was not lacking the joy and the intent of a newcomer. And then the next battalion, [INAUDIBLE]. I was not lacking. On the third time when I visited, I was selected, so from there, we were regrouped [INAUDIBLE] volunteer to replace the 20th division. We were regrouped there from all volunteers from the Armed Forces of the people. My rank then was a private first class. I belonged to the artillery, so all volunteers were regrouped at camp all the time. Then when all the volunteers were there in Camp Aldinado, we created us from the branches of service where we belonged. Of course, I belonged to the artillery, so I was with the artillery group. And then parting group, medical group, every group. So we all just were already grouped, and the size of those volunteers, the number of people that we completed, we moved the [INAUDIBLE] at the time, the Port [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]. Then we were regrouped again by branches of service. Of course, I was trained in separate from the field artillery, so I was with the artillery. So when everything was grouped already, artillery, infantry, medical, logistics, and others, then we moved again to Port [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] at the time. So then we started our training. I can't remember the number of months we were trained. So after the training, there was another group. We would group again to North of Korea. I cannot exactly remember the group where I belonged. So then we went to Korea. We take the LST at the time. You know about this LST? Landing ship, tank. The ship of the Korean Army of the Armed Forces [INAUDIBLE]. Landing ship, tank. They called that LST, landing ship, tank. But we were training for Korea. We retrained again. Retrained at that [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] was a mountainous area. That's where we trained. After our training, then we were shipped to Korea. That was ... I cannot remember the date, but the month was July 1950.

>> '53.

>> Yeah, '53, 1953. So that is it. We sailed to Korea. We rode the Philippine Navy ship, we called that LST. We called that LST. We arrived in Korea July 1950, yeah? 1953. Yeah. [INAUDIBLE]. So that is it. We really [INAUDIBLE]. That was July 1953. Excuse me.

>> That was the Armistice. July 7th, 1953 was the Armistice. Do you remember when the war ... They signed the cease-fire.

>> Three fire?

>> Cease-fire, Armistice.

>> Armistice, yeah. That was already ongoing, the Armistice was.

>> Do you remember a little bit about why it took a long time for them to do the cease-fire agreement? No?

>> I have no idea about that.

>> So what did some ... What did you do during when you weren't fighting?

>> What did you do?

>> When you weren't fighting?

>> Fighting?

>> Uh-huh.

>> Because I belonged to the artillery ... This is the battle pit. This area, we are about 7 to 10 kilometers at the battle pit. It belonged to the artillery canyon. [INAUDIBLE]. So before the infantry people could enter, advance, you had to [INAUDIBLE] with one of our ammunition. So it depends on the front line how the people just kept themselves, the enemy, because there is a radio telecommunication device overhead, and [INAUDIBLE]. So if the enemies have already moved backward, then cease-fire. The firing of the infantry people that ceased already except over here coming from land, but the Chinese communists [INAUDIBLE] come in from the [INAUDIBLE] give you password coming from Manila, [INAUDIBLE] front line somewhere along, well, shall I say ...

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> No, no, no. Somewhere around Yuki. That is the approximate distance from the front line where the enemies and the Chinese are in training [INAUDIBLE] from our troops, the union troops. Yeah. So that is it. That is the system of the fight. Normally, we fight in Korea at the time during the night [INAUDIBLE] during the day.

>> Can you look here? Don't look there. Look here and speak a little bit louder.

>> All right.

>> This the camera. Don't look there.

>> The fighting in Korea at the time was mostly during the night. Excuse me. During the day, everything was done with fighting, but we from the rail [INAUDIBLE] canyon, we have to pile in. [INAUDIBLE] with our service. Have seen some movements there, the enemy, and they request from us a pilot and a server from the artillery. [INAUDIBLE].

>> So you fought during the 3rd Battalion that saw a lot of battles, right? Many battles, many combats, fights, yes.

>> Engagements?

>> Yes, many engagements, right?

>> Yes. That's why I said the fighting during that time was mostly during the night because they know [INAUDIBLE]. Many people were from that place, so all them prepared to go fight during the night, while during the day we kept defending also our positions. They were also defending their positions. But when that mess started, it's like fiesta.

>> So when do you sleep?

>> In our system in the artillery because we have the [INAUDIBLE], we have 10 in a team, we divided that by the infantry. So the first group starts at 6 o'clock, then after 10 o'clock, then after 3 o'clock, then after 5 o'clock. That is the system.

>> And you rotate?

>> We rotate, yeah. Yeah. We rotated.

>> Did any of the ...

>> I am referring only to the artillery. I don't know what the infantry ... The infantry people were just walking on the front line. The artillery group, we have big guns, so we have ...

>> Super bazooka. Super bazooka. I saw super bazooka.

>> Bazooka, for those people in the front line, bazooka. We have that. They have that. But we [INAUDIBLE].

>> What?

>> [INAUDIBLE].

>> What is that?

>> In our place.

>> What is that?

>> Cannon.

>> Cannon! Cannon, oh.

>> Cannon. Cannon, yeah. We had the cannon and myself. That's why sometimes, I can't understand you because during the night, our ears are popped.

>> Oh!

>> Up to now I can't ... Specifically the right one because I used to fire the cannon, so the blast of the cannon will affect your ears.

>> Oh! No earplugs?

>> No earplugs. They do not encourage us. The officers at the time were not ... Excuse me. We were not told we need that. So when you hear ... Specifically myself was the one who was pulling the lanyard of the [INAUDIBLE]. No. You cannot hear that good now. You cannot ... Let's say I'm the one firing the hose. If you do not pull that ... I'm the only one pulling it, but there is a command. There is a command on the [INAUDIBLE]. We have the command in the rear, which is [INAUDIBLE] around 50 meters back. That is the one giving the command. When they give the command ... There are six cannons, but they are just for [INAUDIBLE]. So when the six cannons are ready, you report to the one giving the command. Number one, ready to release, not in the line of [INAUDIBLE] but number one is posted as number one. Number six, again, is [INAUDIBLE] because there are six cannons [INAUDIBLE]. When the six cannons are ready, the command post, the personal at command post, "Ready?" because there is the one pulling the line. Bam! And the cannon fires. The system we used.

>> What do you think about Filipinos' contributions in the Korean War?

>> Filipinos?

>> Yes because, if you know, there's 21 nations that fought in the Korean War all over the world, but what's so special about Filipinos?

>> I cannot exactly describe it, but I belong to the [INAUDIBLE], as I said, It's about 7 or 8 kilometers away from the front line, from the infantry people, before the infantry people who are engaged in fighting, so I could not pass this. But what we hear from them is the fighting starts because the fighting starts the moment it gets dark. It starts already after the morning when it's already daylight again. That's just how we fight people.

>> You're a part of the association, right? You're a member of the association?

>> Oh, yeah. I'm a member of the Veteran's Association.

>> Yes. Aren't you a proud of the association you're part of, a member?

>> Yes.

>> Right? So for, let's say, an American or some Koreans, they want to know about Filipinos in the Korean War. What would you say? "Okay, we did this. We were" ... something special about Filipinos.

>> No, there's no such thing. We are equal there. Like other ... and like other UN troops of the time, especially the Thailanders, they can't understand English, and some others can't understand English. For the Filipinos, we talk English with the Americans and other UN troops.

>> Oh, so it was easy to communicate?

>> Right.

>> Yes, easy to communicate, which is very important. Communication is very important.

>> Yes. Yes. Yes, important.

>> So they relied on you for other ... Right, they relied on you? Ethiopians, they couldn't speak English well, right?

>> Right.

>> Turkish, they couldn't speak English well.

>> No.

>> Yeah.

>> No. No. No. They're like [INAUDIBLE]. The Turkish are there. We can't understand. We can't [INAUDIBLE], not like that. They were ready.

>> Do you remember seeing Greeks, other people? Do you remember?

>> Other nations, you mean?

>> Yes. Yeah.

>> Yes. Thailanders. What other nations?

>> Greece.

>> Plenty of the United Nations. I can't exactly remember. I can only remember the Thailanders, Filipinos ... No, I can't remember.

>> Greece!

>> And do you remember seeing Koreans? Do you remember seeing Koreans?

>> The Koreans, yes.

>> Civilians?

>> There were troops from Koreans there already, but it's really hard to say something about the Koreans.

>> Children? Orphans?

>> Yeah, children, orphans, plenty. Tough job when you move them. You go to Seoul. Tough job visually to see the people [INAUDIBLE], and we have [INAUDIBLE]. We are going to come [INAUDIBLE].

>> They were so poor.

>> Yes. Yes, so poor. [INAUDIBLE] poor.

>> But now ...

>> Yeah.

>> Right? You've visited Korea. They're big now, right? Big, tall, and ...

>> In Manila. In [INAUDIBLE] they can't talk English.

>> Yes.

>> There were many times when we go to Korea for the revisit program, and [INAUDIBLE].

>> [FOREIGN LANGUAGE]

>> Yeah, I've been there in Korea.

>> It's amazing, right? Yes. Yes. Yes.

>> You can see the progress in the restored areas. You can't remember where was the fight, can you?

>> I hope you know that ... I hope you're very proud.

>> Yes. Of course I am.

>> We're very thankful. We're very grateful. We're very grateful.

>> Other nations, believe in us, the Filipinos, number one. We can speak English.

>> Yes. And you were experienced from World War II?

>> No, I did not ...

>> No, I know. Not you, but Philippines. Philippines ...

>> Yeah, Philippines.

>> Philippines fought in World War II, so you had a trained Army. Yes. Yes. Thank you so much for your time and your service very much.

>> Hey, everybody. I am now inside the museum hall of Veterans' Association, and I wanted to share some stories of the veterans in their own words. So with me here today, I have four Korean War veterans. There are only 500 remaining in the entire country. Seventy-five hundred went, but here they are. Now first time before I start. How old do you think my grandpa here, Max, how old do you think he is? Okay? If you guessed 86, not even close. Grandpa, how old are you? How young are you?

>> Ninety-six years young.

>> Ninety-six years young. I think he's living up to his name because his name is Maximus Young, so we will start with him because he is the youngest. Okay. So I'm going to start here, Grandpa. Do you want to face this way?

>> No, it's okay.

>> Okay. So please tell us your name, your ... Oh, he also served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. Yes, but right now, could you show us ... tell some of your experiences in the Korean War?

>> The Korean War?

>> Yes.

>> Well, I'll first explain that we had ... We arrived there, and the first night, we were in a boat of [INAUDIBLE]. Now we were issued sleeping bags. The following morning, it was a surprise. Instead of my soldiers waking up at 5 or 6, at the earliest crack, we were screaming. It was, some of their bunkers ... some of their sleeping bags were with snakes, so we were sleeping in a rice field with a ring of snakes. [INAUDIBLE] and from there on, we walked and started on, and from there, we would stand up [INAUDIBLE] and our supply line, we went by the third army among them. [INAUDIBLE]. My son, Julian Sanchez, not in that unit, and they were disturbing our supply line. Some of our crops were destroyed. Some of our crops were broken outside, so what the country did was for us to [INAUDIBLE], was changing because the place where most of the North Koreans were. It was in November, in mid-November of 1951 in November, [INAUDIBLE]. Now as we were going north, [INAUDIBLE] our craft hit land mine. Land mine more less throw our craft about 5 to 10 meters high and hit some people that were in a car, but they were thrown up. Now that was a signal then that we were [INAUDIBLE] because in military operations, usually [INAUDIBLE] before there is a [INAUDIBLE]. So [INAUDIBLE] that the land mine was an initial warning to the troops that an enemy is coming. As we passed [FOREIGN LANGUAGE], many people went straight, and then in a certain area, it was about 800 yards. We saw later on, [INAUDIBLE] pass the bank, that's where we start finding the guys. It was 10 o'clock in the morning.

>> I just want to stop here because isn't his memory impeccable? How do you remember all the details, what time it was? Oh, my goodness. Wow! I barely remember what time it is right now.

>> Literally, when you visited me, you were ...

>> Aw.

>> Aw.

[ Chatter ]

>> Aw.

>> Seeing you bring this feeling back.

>> Aw.

[ Chatter ]

>> And when he was farming last year, I visited him in Manila. He was at the hospital, so I visited him in the hospital wearing a mask.

>> Oh, yeah, wearing a mask. [INAUDIBLE] if this is the end, there were about 10 bunks. All of those bunks was [INAUDIBLE] in the area. So [INAUDIBLE]. All of the [INAUDIBLE]. Now our plan [INAUDIBLE] the first job is follow by the soldiers, so on and so forth. [INAUDIBLE]. Now when they find us suddenly, we were all paralyzed. Even the soldiers had to float [INAUDIBLE]. So what I did, what we did was [INAUDIBLE] and found out that the soldiers there were dropping, literally dropping, and certain [INAUDIBLE] certain area. [INAUDIBLE] ready for an attack. So it was terrible. [INAUDIBLE] what I did, I picked it back up and then turn right to the hills, but it so happened that [INAUDIBLE] the right side wasn't prepared, so we wake up with [INAUDIBLE]. So what I did is, I told my brother to lift up, but [INAUDIBLE] and this was hit. So what I did, I opened the compartment [INAUDIBLE]. You can see the whole area [INAUDIBLE], and so the soldiers [INAUDIBLE] in different sections. So I opened my [INAUDIBLE]. There was no protection. I suddenly walked and more or less ducked and found five boxes of [INAUDIBLE] and started firing at the roof where they were assembled. As I started fighting, [INAUDIBLE] all of them jumping. No, no, [INAUDIBLE], for every five bullets, there's one tracer to find out where the direction of your firing.

[ Chatter ]

>> I could take the firing ... tracer bullets. [INAUDIBLE] a tracer, which will find out where you bullets went through. So I started fighting out on the trenches. I also fought. There were soldiers. There were soldiers. I continued fighting for almost 10 minutes, so when I started fighting, the soldiers sat up and started fighting, and all of a sudden [INAUDIBLE] supported ...

>> Yeah.

>> ... supported the fighters.

>> So we just finished watching this ...

>> After 45 minutes ...

>> Yes, and he was a hero.

>> Wow.

>> Well ...

>> And he's not saying it.

>> That's just ...

>> And he's not saying it, but he's a hero. You know what I'm going to do? I'm going to show ...

>> Okay.

>> Look at him, his medals. Right? And he received recently last, 2 years ago, the Order of Military Merit which is, I think, the highest honor from Korea from the president, so look at the medals. So this was donated to the museum, and now it's displayed here. That is Grandpa Maximus Young, and I know, since I remember from last year, his secret to staying young is, he's active. He plays a lot of badminton, and he's very, very optimistic, and he has a beautiful wife, so that's the secret. Okay?

>> And in for mean time, stop calling me Grandpa. I'm just as spirited and handsome as you are.

>> Yes. Well, I am also going to ask ...

[ Chatter ]

>> General. So he retired as a brigadier general, right?

>> Yes. I am a retired general.

>> Yes.

>> And [INAUDIBLE].

>> Yes.

>> But I was only second lieutenant at the time I went to Korea in the 2nd Battalion, Number Two, and [INAUDIBLE]. After they said, "Hey, you, check on the city," [INAUDIBLE] there was already a cease-fire, and the United Nations officers were already at the demilitarized zone, but then upon arrival in [FOREIGN LANGUAGE] or that portion of the demilitarized zone where in the United Nations forces were laid out, we were assigned a division reserve of 24th US Division, the 2nd Battalion Combat Team. So actually by the time we got there to Korea, [INAUDIBLE] there was no more fighting, but then there was a cease-fire but no peace, and I [INAUDIBLE] that there were possibility that the Communist Chinese would resume their infiltration through the demilitarized zone.

>> You're absolutely right. So even after the cease-fire was signed, there were many skirmishes.

>> That's true.

>> They were still fighting, and people even died ...

>> Yeah.

>> ... on both sides.

>> In fact, several of my men, about eight men, when we were at patrol, the area in [INAUDIBLE], from the other side blew up the last night, and it holds, what, of eight men, of my men, in 2nd Battalion [INAUDIBLE].

>> And he retired as a brigadier general for how many years?

>> I've been a brigadier general since 1970.

>> And he's only 86 years old.

>> Ninety-two.

>> Ooh, just kidding. Ninety-two. Oh, man. I think I need to move to the Philippines because something you're drinking there, you seem very young. Okay. This is now the president of pep talk. Now he's 90, 91 years old.

>> Yes, 91 years old.

>> Young, yes, what was ...

>> I went to Korea. I was 25 years old.

>> Yes.

>> Second lieutenant, [INAUDIBLE]. Our location deployment was [FOREIGN LANGUAGE], Bali, [INAUDIBLE], so [FOREIGN LANGUAGE], Bali, [INAUDIBLE], a few weeks there, but up there about, I think, 14 months. There was [INAUDIBLE] brigade, [INAUDIBLE].

>> Yeah.

>> [INAUDIBLE] more than one company. So we were made to ...

>> Replace them.

>> ... to replace them and climb up the hill.

>> Yes. I saw the movie, in the film.

>> Yeah. And as we go up passing by the tree where [INAUDIBLE] this pile-up, [INAUDIBLE] such and such there, dead people, so sometimes, you have to think about it.

[ Chatter ]

>> The smell of the dead and the injured. I know. You still remember that, huh?

>> Oh, yeah.

>> Yeah. We get to remember.

>> Well, I hope that now you reflected, and it's not traumatic for you anymore. I hope that, okay, that you don't get nightmares.

>> Very good.

[ Chatter ]

>> [INAUDIBLE]. We trained.

[ Chatter ]

>> Yeah.

We trained.

[ Chatter ]

>> So it [INAUDIBLE], we will never die.

>> Well, I hope you will live forever. Okay. Last but not least, the youngest of the bunch. You're the youngest, right?

>> Yep.

>> Yes? Okay. Now tell us your story.

>> Oh, very simple one. You might be interested to know why I went to Korea.

>> Okay. I am interested.

>> I was 18 years old, newly graduated from high school when someone [INAUDIBLE] ...

>> Uh-oh.

>> ... and me, and because of my desperation, I thought, I'll voluntary [INAUDIBLE].

>> Oh!

>> So what I did was got myself listed as a private in April of 1952, and on March of the following year, I was already going.

>> Mm-hmm.

>> I was barely 21 when I was in Korea, and how the Koreans do it, [INAUDIBLE] pretty girls, very amusing.

>> Amusing? Oh, amusing.

>> And actually 3 months after we were to Korean front lines, I enjoyed my first taste of R & R, meaning rest and recuperation where I met beautiful women. I tell you, they were very accommodating. In fact, The second time I met her, after 1 month, she was already my girlfriend.

>> Oh!

>> So fancy that.

>> Yeah, so ...

>> No. I feel very lucky in Korea, but I arrived in Korea in March of 1953. I was promoted to [FOREIGN LANGUAGE], one stripe, one round, I get.. After 2 months, corporate. After 5 months, sergeant.

>> Wow.

>> In a period of 5 months, I got three stripes.

>> Wow!

>> The third was the target. In September of the same year, in September of 1953, I was sent to Tokyo, Japan, to be the rising sergeant of [INAUDIBLE] to the United Nations Command in [INAUDIBLE].

>> Wow.

>> Yeah.

That was a bold moment.

>> Yeah.