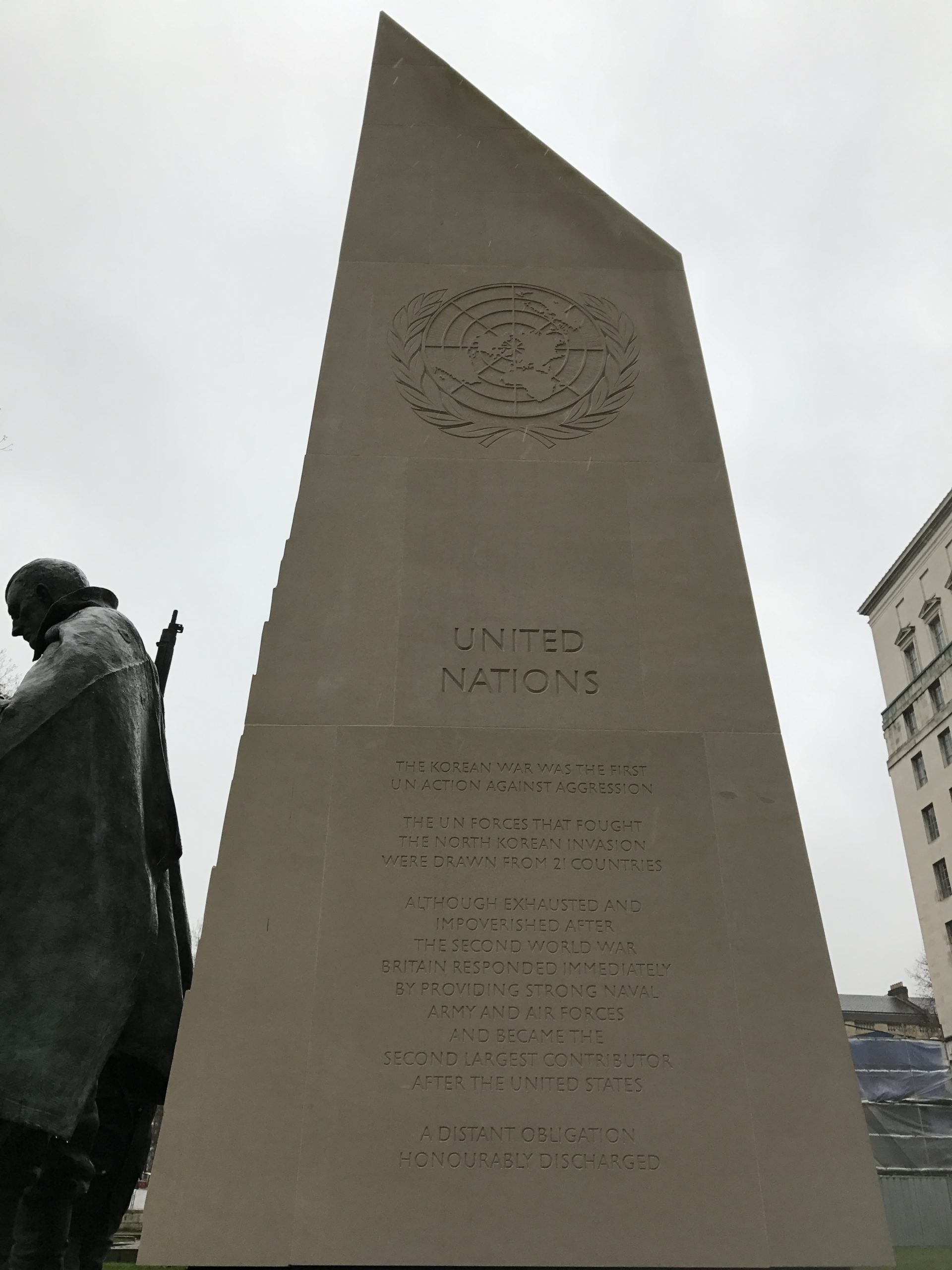

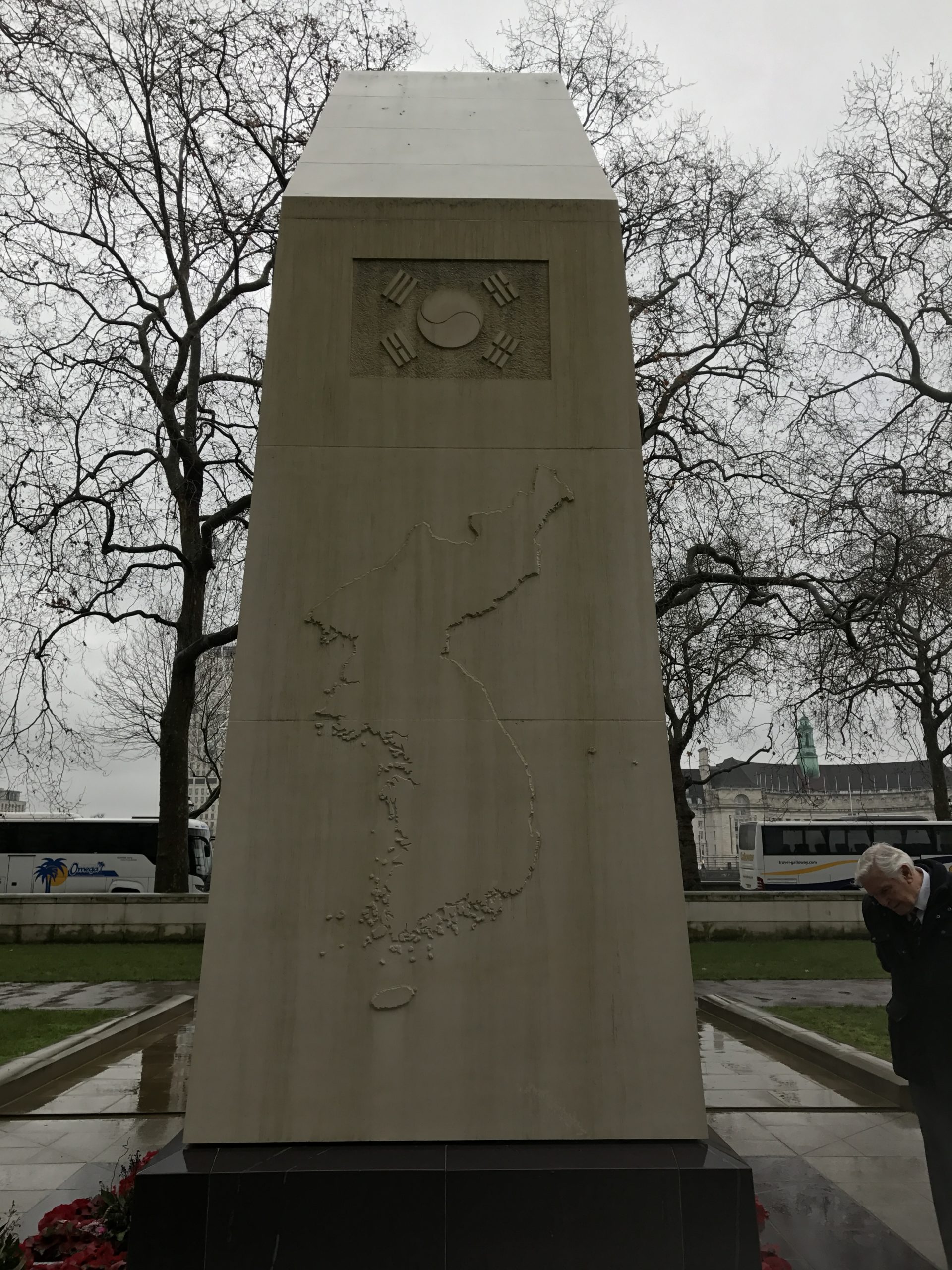

>> Hello. My name is Roy Painter. I'm a trustee of the British Korean War Veterans Association, and I served some time in Korea from 1952 to 1953 as a national serviceman. Most of the time, boring, some exciting, some of it very scary, but that was the way of the world then in 1952. I didn't think much of it when I came home, but now it means an awful lot to me when I see what the Korean people have done and very pleased and proud that it part of this regeneration of Korea, and I realized this. Now as you get older, you appreciate just how important it was that the part we played in the British Commonwealth Division and my colleagues. Forty-some of us never came back, like my friend Brian. He was only 20, who life dealt a bad deal, an orphan, in any case, was living with his grandmother, I'm afraid didn't come back and is still in the Korean cemetery. I suppose that's all part of war, and the bad things that happen, but the good things is that Korea is on its feet. The people are very generous to us, the Korean people, and it means so much to me that they have done this, and in some tiny cog in a bigger cog in a bigger cog, I played some part in it. Some things happened to me there. I went on a rest and recuperation leave, and I brought back a 1 yen. What that's worth now, I don't know. I visited a Buddhist temple while I was there, which, again, enlightened me. This is a couple of colleagues I had. That was me there, looking about 10 years old, but it was 1952, and we were all young and didn't care very much, some more photographs. The entertainers came out. That was a lady called Carole Carr, who was a very famous singing star in the '50s, and there she was. This here is my first introduction of working in the career, the signal office before I got sent up with the others and where it all happened, and this here is the ship I got sent home in, not much bigger than a Thames barge, actually, but there we are, but I've got some other things I could tell you if you want. Oh, this here, I was very pleased that I got invited back to Korea in November '14, and the generosity of the Korean people and everybody. The Ministry of Patriots awarded me the peace medal, and this parchment here, which I think I'm very proud of, which I hope in generations to come, my grandchildren, great-grandchildren, great-grandchildren will look and feel as proud as I am when I received this. Well, also, they fished out these Christmas cards from the American people. I don't think she realized it was going to an English person, but, nevertheless, it was a delightful, delightful Christmas card from a grandmother in America wishing us all the best and that someone was thinking of us, which I thought was very, very generous of them. I did reply to the lady, and I hope she treasures my reply as much as I treasure this Christmas card. Oh, and there's lots I could tell you, could go on forever, really. At 60-odd, the UN decided to declare war in Korea. Now most of the people in England didn't even know where Korea was. You got to remember the time. We were still on rationing. We were the poorest country in Europe still. We'd been bombed out. My father had been in the army for 5 years. My house had been bombed. We were sleeping downstairs in two rooms, sleeping on mattresses on the floor. By 1945, that was then. I left school in 1948, and, of course, in 1951, like other young men, I had to do 2 years' National Service, which I was called up. I went to various parts of the United Kingdom until some time in I think it was March when I was in there, when I was called into the colonel's office and told, "You're off to Korea." Korea was some Asian, some ... The other side of the world, which of course it was. Anyway, pack your gear, go home on leave for 2 weeks, which I did. Wound up in Liverpool on a boat, had 6 weeks of very pleasant trip to Busan, saw parts of the world I never would have seen. We slept on-deck, and we got to Busan, where we was introduced to Korea. Spent 1 week there getting acclimatized, and then we boarded a train to go to Seoul, and it took us 37 hours, stopping, starting. We got to Seoul, out of Seoul. We got on Canadian tracks. We then went another 5 hours, and suddenly the reality of it hit me. I could hear guns firing. I could hear bangs. Oh, dear, this is the reality, but we all made silly jokes and said silly things, and I got to where I had to go in the Commonwealth Division, was fed, watered, and we all had to swim in a local stream, got all the dust off us, and then I was sent to the signal office where I was introduced to the workings of what the army life was really about, and strangely enough, within 2 days, the first message I received was of a schoolmate who sat next to me at school had been wounded, shrapnel wounds, head, severity, severe. How small a world is it? Then the next 6 weeks, I got acclimatized to everything and became what I suppose was a working soldier. Sergeant then come down, said, "Okay, Painter, we're going to cook your goose. You're going up to the Aussies now," and then in a jeep over the Imjin River, carried on. The gunfire got louder and louder and louder, and suddenly reality started dawning. Oh, dear, this is what it's all about, and I went until I was attached to the first World Straits Arrangement, and I was introduced to the colonel, and the sergeant, he was a grisly old Aussie who had been in the army for years, said, "This is your new English operator, a pommy," he said because they called English pommies. This is your new pommy operator. Wise operator said, "If you don't mind me saying so, sir," he said, "I think the poms is still sending us kids. They're still shipping young one on their mother's tit. They all look kids." Anyway, it was a start of a 3-or-4-month acclimatization. I learned very quickly to tell the difference between outgoing shells and incoming shells, but it wasn't that bad because everyone else was used to it. We did guard duties, and I was always impressed by the clarity of the sky at night, especially in the winter. It was so clear and clean-cut, and I looked at the stars, and I thought, "Wow," and I should try and work out in my head how far away it was to go home, 6,000 miles. If I walked it, could I walk through Mongolia? But then a routine settled down. I was a wireless operator, and you spent 6 hours on-duty, 6 hours off, but mostly it was fairly easy until sometimes, things got slightly naughty, and mortar bombs started landed on us, but it only lasted a few minutes, but it still used to make you scared, and people said they wasn't scared are telling fibs because everyone gets scared, but then you did guard duties, and you'd look at a bush, and you'd think, "Is that bush moving? Is it someone really there?" And I said ... I think peoples turn to religion. We all make false promises, and the shells we'd land on said, "Please, god, don't let them come any nearer. I will go to church," knowing I wouldn't, but time passed, and then I got attached to the Americans, and that was a lot of fun. They had food I'd never seen before, chocolates and steak and ham and eggs for breakfast. It was unbelievable because you have to remember that England was still on rationing. We were still on starvation rationing in England, but sweets, and time went by, and suddenly I'd been there almost a year, and I went on one leave in Tokyo, the rest and recuperation leave, which was fun, 5 days, lots of boozing and things like that, but that's what young soldiers do. Isn't it? And I came back, and where I could ... It did change my life. I remember looking a the Koreans, and I can remember them opening up a tin of bacon. It was a big tin. It was bacon inside. They took it out, and I remember saying to my mates, "Korea will never go back to being peasants again. They've moved 400 years in 2 years. They've seen now what the rest of the world has got," and I can remember these two young Korean guys taking the bacon out, and I thought, "They're eating the same as us, wearing the same clothes." Of them, those that were lucky enough to be with the Americans got all the goodies. They don't want to go back to eating rice and fish. Korea is going to change. They're going to want what they're ... and quite rightly so. It was a few moments. We never saw many civilians, but I can remember one was a Korean peasant lady who was way down in line, and she had a baby strapped to her back, a little boy, and as most soldiers do, I wasn't mean. I gave him two bars of chocolate, and the gratitude of the Korean mother was so immense that even at 19, I was moved that for two bars of chocolate, life should not be like this. People shouldn't be treated like this, and how could the north come down and raze these villages to the ground and kill people? I suppose it was part of my growing-up process. Wasn't it? This was wrong. This was wrong, and was I pleased I was taking part of that, of helping? And eventually time came, time to come home, and I did, and I must confess. I put it out of my mind, Korea. I put it out of my mind, but occasionally on my own I would think about it. I'd think about it. It never ... People say they have, what, post-traumatic ... I don't think it ... I had a few sleepless nights. I would wake up, and I wanted one experience, this, okay? When I went to an army camp in England some years ago, and they'd recreated the 1914 war with sandbags and shells, and I went through, and the shells started whistling, and my stomach did turn over. My tummy turned to water, and it brought back memories, but I soon got over it, like most people decided. I'm not sure about post-traumatic stress, but if people suffer from it, then I feel very sorry for them, but then I got a phone call in the ... oh, dear, from a man called Rod Larby. He said, "I know if you don't like to see your man's grave, Brian Clackett." And of course, the memories come flooding back. I said, "No," and Brian was only 20, and life dealt him a bum deal, which I think I said earlier. He was only 20, and he was an orphan. By 12 o'clock, he was dead, and so I became involved in the British Korean War Veterans Association, so I'm going to meet my old pals, told lots of lies to each other, didn't we? As we always did, but they were older. You remember some of that. Do you remember him? Do you remember him? Until eventually I went back on a revisit in November 2014, and I'm so pleased I did. The change in Korea is just phenomenal. They're the 10th largest economy in the world now, and if winning this war in South Korea could do this, why can't North Korea? Why can't other nations use this industry and do good things? Anyway, on the revisit, they arranged for me to see Brian's grave, and I must confess. I did get emotional in this time because it shouldn't happen to a 20-year-old, but I saw his grave. The graveyard is kept absolutely immaculate. The Korean people are ever-thankful. I don't mean grateful but thankful, which is nice, and isn't it a pity that the north is still the same as it was? Isn't that a shame? Isn't it? You'd think that ... words fail, especially with this lunatic in charge keeps his people in servitude and slavery, and we can only hope that all the people that died didn't die in vain, and that Korea becomes one nation. It's leapt from 1600 to the year now 2000. I can't believe it can carry on as it carries on now, and all these people died for nothing. You know? Fifty-six thousand Americans, over 1,000 Brits died and 1,000 were taken prisoner, and let's hope that we can all learn that man's inhumanity to man can't go on, so now in my 80s, am I pleased I did it? Oh, absolutely, I'm pleased I contributed in some way. I made friends and comrades I would never have made. I experienced something I would never have experienced before. I was privileged, just privileged to take part in some tiny call freeing South Korea from the yokes of North Korea, and so, really, I can go to my grave saying, "Well, I did contribute something to the world, albeit forced to do it but pleased to do it," and let's just hope that in my lifetime, Korea can unite. One thing I did forget was on Christmas 1952 at midnight, all guns stopped firing, which just very quickly became an eerie quietness. It was like, but on Christmas morning, strange enough on the wire before the minefields, the Chinese or North Koreans had left Christmas cards and little presents like toothpaste, razor blades and other things, and the Christmas cards were specifically worded for English. Hello, lads, merry Christmas. I hope you're enjoying some presents, but do you really want to fight for the American imperialists? While you're here, they're taking your girls and wives back home, and you're fighting a useless war. Do you really want to fight this war? What they didn't realize, it was counterproductive, of course, because we all laughed. It didn't really have any effect on us at all. We just laughed because we could see through this propaganda. It didn't really affect us. I will look for this card again because a picture is worth 1,000 words, so I hope I can find it and some other, but, of course, I wasn't expecting this, so I really don't know where I've put it, but I really must try and put this all in order for future generations.