Australia Sydney (4)

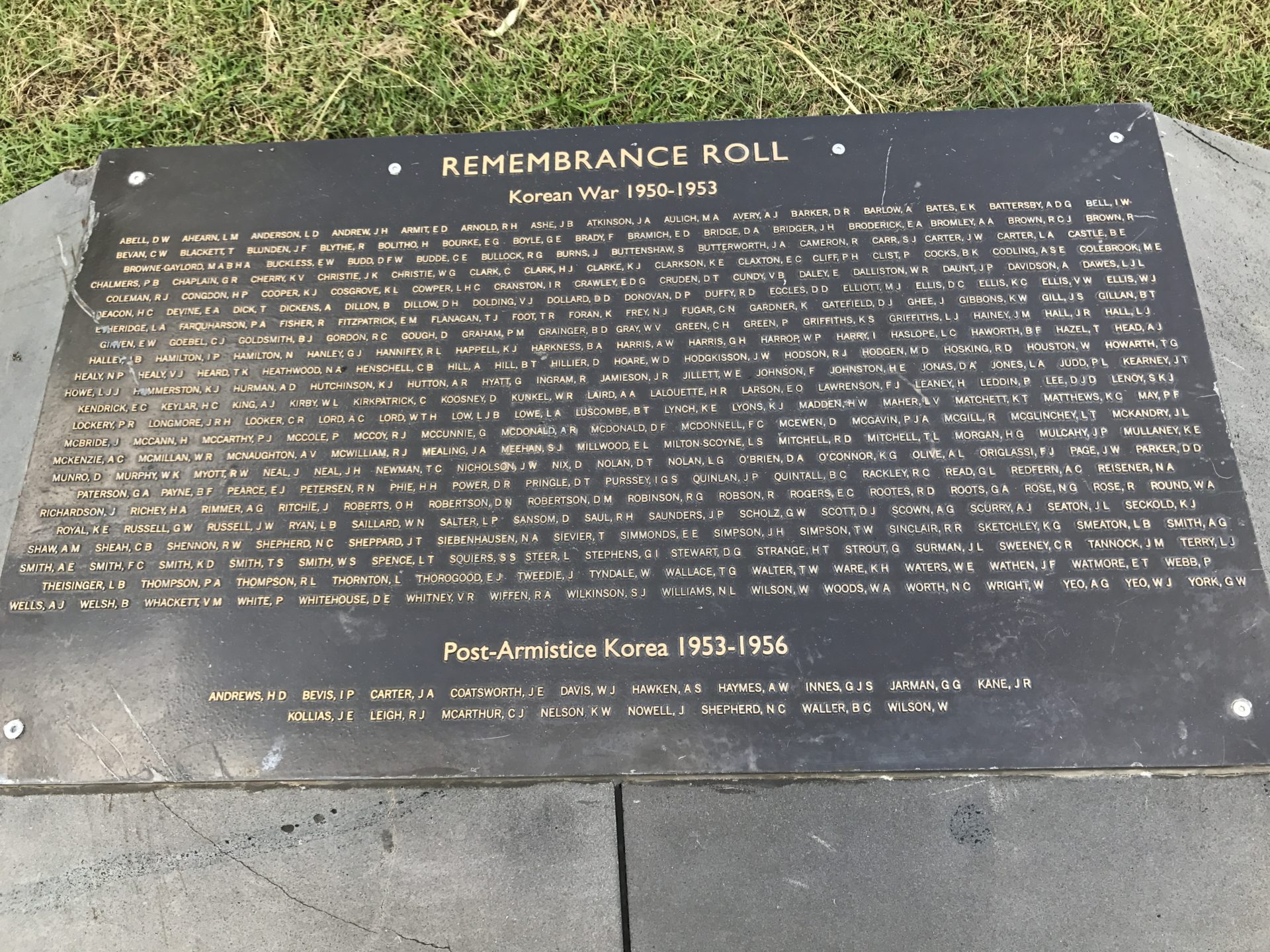

>> Good morning, or good evening, Hannah. My name is Ian Crawford. I am a retired rear admiral in the Royal Australian Navy. I served in Korea in 1950 and '51. At that time when I first arrived there, I was an 18-year-old midshipman serving in the Royal Navy light cruiser HMAS Shoalhaven. We were intended to be the flagship of the East Indies Station based in Trincomalee in Sri Lanka, but when the Korean War broke out, the British had to withdraw a cruiser from the Far East, and we were very quickly prepared to go to Korea. On our way there, we were diverted to Hong Kong to pick up the 1st Battalion, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, who, together with the Middlesex Regiment, who were carried in the HMS Unicorn and, were the first British troops and the first non-American and Korean troops in the Korean War. They were to form the 27th Brigade, and the Australian Army, 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, joined later in September to form this brigade. After delivering the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders to Pusan, and at that time, Pusan Perimeter was at its smallest, we landed the Argylls and the Middlesex Regiment from the HMS Unicorn, and we went about our naval duties. Very soon after that in September, we were part of the cover force for the landing at Inchon. We were escorting the British carrier, HMAS Triumph. Two Australian destroyers were with us, HMAS Warramunga and HMAS Bataan, and they stayed with us for most of our time on the west coast. The British, various fleets, together with the Commonwealth navies, formed the West Coast Task Group. On one occasion, we were transferred to the East Coast, and we went as far north as Chongjin, which is 2 miles from the Russian border. That was as far north as you could get in Korea, and we bombarded there. By October, there was the general feeling ... The forces, after being released from the Perimeter in Pusan, went up to the peninsula and across the 38th parallel, and the feeling was the Korean War was over. So the British withdrew to Hong Kong but not us because we were from the East Indies. We had no families in Hong Kong, so we stayed there, and we were just starting a refit in Kure in Japan when the news came through that the Chinese had entered the war, and they were making fast progress down the peninsula. We were quickly put together and diverted to the Taedong River, which is in North Korea, which is the entrance to the river that leads to Chinnamp'o, which is the port for Pyongyang, so we were diverted there in the belief that we were going to have to evacuate large segments of the Army and a lot of civilians. In the event that we evacuated a lot of civilians, we in a light cruiser could not get up the river, the Taedong River. It was very narrow, badly chartered and the sandbanks were not evident. So there were three Canadian destroyers, two Australian destroyers and one American destroyer. One Australian destroyer went aground, one Canadian destroyer got a wire around its propeller, so eventually only two Canadian destroyers, one Australian destroyer and one American destroyer got up to Chinnamp'o. Supervised the evacuation, and the evacuees came down in the ships and in separate pairs, and then they destroyed the Port of Chinnamp'o. Our main operating base when we were on the west coast was an island called Daecheongdo, which our captain used as a base, and everybody followed his example. It became a place where we convened to meet with South Korean guerrillas and exchange information, where our smaller ships took shelter in bad weather while we made our forays up the Gulf of Korea very close to the border with China. The Chinese and North Korean advance continued. We were in Inchon, and it became evident that Inchon was going to be uncovered, and so all the American stores had to be destroyed, and our ship was the last ship out of Inchon. We continued to go into Inchon, moving from position to position so that people would not fix us for counter-bombardment from batteries ashore, and we at times came under fire from these batteries, and eventually, we were 20 miles behind the front line, so we had to leave the port. The great problem was the extreme cold. It was the coldest winter of the century. It was so cold that our close-range weapons, pom-poms, Oerlikons that we had to move the mounting every 15 minutes. Otherwise, the lubricating oil would freeze. And at sea, when the spray came over the bow and hit the superstructure of the ship, it turned into ice, so it was cold. We stayed on patrol for a long time. I think we spent more time on patrol than any other ship. At one stage, we had patrolled 43 days. So the important thing was to keep the sailors entertained, to make sure they got their mail, and we provided our own entertainment. I know for sure, Roseanne, Bob Hope and a lot of Hollywood people came out and did sing to the soldiers. That wasn't available to us. We had to provide our own entertainment, which we did, and it was a great success. The other thing was the feeling we had because everyone thought the war was over, and everybody had gone south to Hong Kong, and we were quickly pushed into the breach. We felt very lonely. We could feel the malevolent omnipotence of China bearing down on us, and morale was very, very low. There came a message from families, from Littleton from families in England because I was the only Australian in the ship. All the others were British. We'd be mentioned in the news, and we were going to get a medal. Now, that amounted to recognition, and one of the most important features for any serviceman, for his morale, is recognition, and this medal was awarded, and I always maintained that recognition is important for morale while serving and for the peace of mind of veterans in their older age, and this has been a principle that has guided for a lot of my time since the Korean War and the various studies that I've done. I've been involved in many studies. The Australian government has been very proactive in trying to determine the problems of the Korean War veterans, and they carried out three studies, health studies, cancer incidence studies, to find out why there was such a large number of Korean War veterans dying early. We had the very comprehensive studies, which at one stage was made available to all other members of a committee that I was working on in Korea for their information. I have been asked by the government to do other studies. We had quite a lot of Australians serving in Korea for the 5 years after 1953, and it was called the post-Armistice period. I was cochairman of that committee, which once again, was motivated by the need to recognize the service of these people after the Korean War because we had people who died there. We had 18 people die during this post-Armistice period. Once again, the recognition of these people and the service of these people was so important. And I'm still involved. We have 43 missing in action. Some will be in the demilitarized zone. Some will be in North Korea still. Many will have been recovered, and we are trying to develop a process where ... And those who were recovered who were Caucasoid will probably be in Hawaii where the Americans take all their casualties, all their dead from all wars who have not been identified, and there is a process using DNA and dental records, and we are trying to progress more actively on the part of our government to identify these people. Also, I started the program for an Australian National Korean War Memorial. It became a big hobby of mine. At that time when I was thinking about it, we had one memorial on top of Anzac Parade, which is called the Australian War Memorial, and as far as I was concerned, that was the memorial for all wars, but because the Vietnam war was so politically sensitive, the government decided to give the Vietnam people their own war memorial. As soon as that happened, I said, "Okay, they've got their memorial. We have to have our memorial." So I gathered together some colleagues, and they suggested others, and we went through the process of raising the funds, getting the government's agreement to give us a site on Anzac Parade for the memorial, to do a design brief of what we wanted to be put out to a design competition for a sculptor and an architect to design our memorial, and then eventually, to supervise the construction and then the dedication of the memorial in 2003. The design was interesting. I knew that the sailors, soldiers and airmen wanted figures that they could identify with, but the winning design didn't incorporate any figures at all, and all my colleagues said, "That's the winning design," and I was the chairman, and I said, "I don't want it unless we have figures." And the architect and sculptor was flexible enough, and he said, "Well, I think we can remove some of the poles," which he had put into the design, "and make space for the figures." And we had three figures: a sailor, a soldier and an airman in their winter garb. He had some misgivings initially, but on the day before the dedication of the memorial, and it was all there, and it was a grand style, he came up to me and said, "It works." We were very happy about that. We had another problem. The National Capital Authority didn't like the obelisk that we had there. They said there was too much verticality, and they wanted to remove it, and with some of the fasting thinking I've ever done, I said, "Oh, but that's for the missing in action," and they found that very difficult to counter that argument, so we kept the obelisk. And a few weeks before the dedication and the final erection of the memorial, the sculptor and architect came to me and said, "What plaque are we going to put on this obelisk?" And my wife had taken photographs in Pusan of the missing in action for those with no known grave, and so we transposed the design of that plaque onto an obelisk. We were constrained by ... We wanted to have Korean flora in the surroundings of the memorial, but our heritage people only wanted Australian material, so we were prevented, but some, oh, I suppose 12 years later, they relented, and we were able to incorporate into the design flora from Korea, Korean box, which is placed at every grave, and the Korean Cedar trees, which surround Pusan, so that we were recreating in miniature some of the ambiance of what is in the Pusan Memorial, where 282 of our dead are buried, so that the families can share some of that environment.

>> Let's go back to some of the basic numbers for those that don't know how many Australians fought and how many died and how many are missing and how many POWs there were. And I know that post-Armistice there were some that also served after the war.

>> Right. We do not know definitely how many were there during the active service time and during the post-Armistice, but there is a rough figure that says around 17,000 served for the totality of the time during the combat time and the post-Armistice time. Some people say that the people there during the combat time would be as few as 13,000, which by that measurement, meant that our casualty rate, taking term into consideration the time we were and the number that were there, was a very high casualty rate compared with other wars that Australia has been involved in. So we still have 43 missing in action. Some of them would be in North Korea, some in the demilitarized zone. I think I've said earlier on that some would be in Hawaii. There were, I think, 27, somewhere in the mid-20s, prisoners of war.

>> But they all returned.

>> Not all, no. Some are now included in the missing in action because they would have died in the prisoner of war camp and been buried in North Korea in a cemetery there, which we've never been able to get to. We had over 1,200 who were wounded. Originally 339, and they're now found another person, so 340 killed during the combat time.

>> How do you think Australians remember or know even about the Korean War veterans?

>> Not very well. When I was doing the Korean War Memorial, I went to industry for them to make donations, bearing in mind that because of the winter and the feeling that the Korean War could topple over into the third World War. There was a great demand for a lot of the material that we had in Australia, especially our wool and our strategic materials and some of the minerals. I argued, and I argued in my approach to business, that the Korean War heralded in a period of prosperity for Australia because of the demand for our raw materials. Some people don't agree, but some 50 years after the Korean War when I approached these companies, the corporate secretaries had never heard of the Korean War and wanted to know why we were there. So it is still, for many of the people, a forgotten war. We're trying to make it not forgotten. That is why we had the memorial, so it wouldn't be forgotten, and interviews like this will help us not to be forgotten.

>> So when the secretary said, "Why were you there?" what did you answer? How did you answer?

>> It was a very sound and strategic decision that we went to the Cold War. In fact, the Korean War was the first how war of the Cold War, and if we hadn't checked the communists in rows onto territories that were more democratic, or in the process of becoming democratic, they wouldn't be encouraged to go further, as in Vietnam. So it was the right decision for Australia to be involved and the right decision for Australia to make its own strategic decision to get involved. We did not automatically go to war, as we did in the first World War and the second World War when Britain went into the war. We made our own independent decision and committed our own forces, but our forces were part of the British Commonwealth Organizations, the Army in the British Commonwealth Division, the Navy with the ships on the west coast were led by a British admiral, and the soldiers were very proud of being in the British Commonwealth Division because the last time they went to war with the British force, and that comprised of the British, the Canadians, the Australians and the New Zealanders, and our soldiers were so proud that they insisted that when we did the Korean War Memorial, as well as having badges for the Navy, Army and Air Force on the face of the memorial, we showed the badge of the British Commonwealth Division., so it was very important to them. It was also an interesting time for Australia that up to the Korean War, in the Army, you had to be a volunteer to serve outside Australia. So for the first World War and the second World War, we had the Australian Imperial Force, which is made up of a big group of volunteers. Up until then, if there was a war, you could only serve in Australian territory unless you were a volunteer. So we had to have volunteers to go into the Korean War from the Army. The Navy and Air Force were automatically committed because of their global span, but for the Army, there had to be a volunteer, and somebody wrote a book called "The Last Call of the Bugle," and that was because people think about responding to the call of the bugle as volunteers, so the Korean War was the last call of the bugle to attract volunteers to serve in the Army overseas. Nowadays, we have a regular force that is volunteers when people join the regular force, but we did not have a standing Army in Australia at that time, and we only had a militia.

>> In the '50s?

>> In the '50s, yes. We did not have a standing Army. We had a militia who could be expanded in the time of war, and if there were volunteers, they would serve overseas.

>> For how long?

>> As long as needed.

>> Oh, really?

>> So some people went right through the second World War, 6 years as volunteers. I had volunteered. My father was second in command of a regiment, which is a militia regiment, and he had to cajole and persuade the members of his regiment to become an AIF regiment, Australian Imperial Force, so they could serve overseas.

>> That's very interesting. So let's talk a little bit about Australians who went post-Armistice. Why were they sent post-Armistice?

>> They had been committed to Korea or committed to Japan for part of the occupation force, and they had been promised certain entitlements, which one normally associates with active service. But when the Armistice came, and it was only an armistice, and it still is only an armistice. So we had to present to the North Koreans and the Chinese our determination to hold the line, and so we had a large force of the former Allies who remained in Korea. They didn't get a ... And they felt very proud of this, and they felt that they had been ignored in the recognition that we were giving to those who served during the combat time, and there was conflict between those who served in the conflict and those who were post-Armistice. We had to do a study to decide how we would recognize these people in the post-Armistice time, so I was asked to cochair a committee, and we did a 6-month study and came up with what we felt was the right answer to make up their recognition. They got a medal, which was called the General Service Medal for Korea. They did not get the Active Service Medal, which was for those who were in combat, so we felt that was the right balance.

>> I was surprised to see that there were about a dozen who died post-Armistice.

>> Nineteen died.

>> Yeah.

>> And vehicle accidents, weapon accidents, all sorts of problems, but it was a very intense time over there.

>> Until 1955, right?

>> '55, yes. Yeah, and we had a communication group who remained up there after the main force went through, and they were part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force or communications group.

>> My last question is, well, first of all, have you been back to Korea?

>> Yes, I have. When I announced to the government that we should have a Korean War Memorial ... And it wasn't until we got a visit from the Korean president that we got recognition from the government. I like to think that they were saying, "Hey, we've got the Korean president coming down. What can we demonstrate to him that we have an interest in Korea?" And somebody said, "Well, they're talking about a Korean War Memorial," and the government said, "That'll do." And at the state dinner for the Korean president, our government announced that they were going to dedicated $67,000, and the Korean president stood up and said, "I'll match you," so we were off very well right from the start. Now what ... Your question was ... Oh, Korea! Well, it was at the Korean recognition, the Korean Federation of Industry gave us a huge donation.

>> No, have you visited Korea?

>> Oh, have I visited Korea? Yes. Yes, I had to go to Korea. I said, "I'm going to England to see my family. I am prepared to divert from Hong Kong, which is the route to England, to go to Korea. If you will pay for that diversion." And so we diverted, and that was my first visit. I've been back since on revisit programs and as part of the International Federation of Korean War Veterans Association. So I've been back a few times, and most impressed by the change, from what I saw. In Pusan in 1950 and Taechongdo, which is a very impoverished island in 1950 and '51, so I just never ceased to be amazed. The urban development, modern technology, like the Korean very fast train, or the French call it Train a Grande Vitesse. I don't know what the Koreans call it, but it is the French technology used between Seoul and Pusan. So marvelous technology, and my sympathies are with the Korean people with this threat across the border. And as we're talking now, there's this unease about what might be the outcome of that.

>> I know, for almost 70 years. I truly hope that Korea will achieve lasting peace or even reunification during your lifetime.

>> That's going to be a challenge because it's more demanding than the unification of East Germany and West Germany because, you realize that as well as I do, that North Korea has never been exposed to modern culture. It was part of the Japanese kingdom, and then after the war, the North remained that hermit kingdom, which was a term applied to the whole of Korea. They have never, ever been exposed to Western culture. Places like Albania and the Eastern Bloc in Europe, yes, they have been, but it'd be an enormous change for the people to adjust to, and a great burden fall on the people of South Korea.

>> Well, I don't know if and when and how or whether they should, but all I know is that this war that still hasn't ended should end, and there should be peace, so that at least there's no threat, even if there's no unification. There's no threat of constant threat of war.

>> Yes.

>> I think that would be the greatest honor that would be given to the Korean War veterans who really sacrificed their lives, their time to defend Korea.

>> I agree entirely, Hannah. And the other thing, it made us realize that the Asian culture is different, and we had to adjust and understand that. Those of us who have been back and have been sufficiently interested to study the cultures of East Asia, which is China, Korea, Japan, and realize that each one of those is different. So trying to achieve harmony in East Asia is not an easy thing.

>> It isn't, and that is why, all the more, thank you for your service. One last question, you retired as Rear Admiral, right?

>> Yes.

>> What was your rank when you were in Korea?

>> Oh, midshipman.

>> Oh!

>> At 18. I had my 19th birthday in Inchon.

>> Wow. How many years were you in the Navy?

>> Forty years.

>> Wow!

>> I was in a British ship because when we left our Naval College in Australia ... Because we didn't have a big fleet, therefore we didn't have the range of experience of a large fleet. So at the age of 17 leaving the Naval College, we went and served with the Royal Navy, with the British Navy, for 3 1/2 years. And so ...

>> And you were born where?

>> Here, in Sydney.

>> Canberra? Oh, Sydney! Not Canberra.

>> No.

>> Okay.

>> No. No.

>> But you lived in Canberra for a while?

>> I lived I Canberra for 30 years. When you got old in the Navy, you end up in Canberra, which is where the headquarters is.

>> Yes, of course.

>> And our children went to school there, but I finished the Korean War Memorial. Kathy didn't like the cold of Canberra. Our children had moved to Sydney and got married and had children, and she said, "We're going to Sydney." And here we are.

>> And here you are. Well, thank you so much, again. This is wonderful.

>> Yeah.