Click on different countries and cities to explore Korean War memorials around the world!

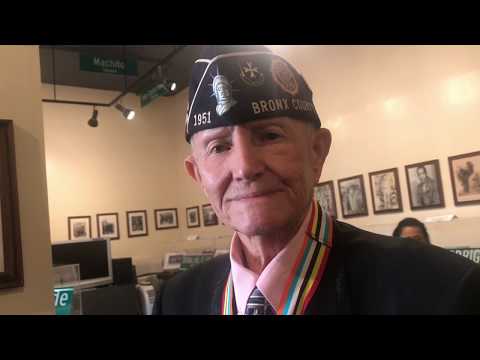

>> Okay, my name is Leonardo Ayala. I was born February 14, 1935, 1 more year older than he. Yes, [INAUDIBLE].

>> When did you volunteer?

>> I volunteer in … I think that was in January 1953, and they call me in March 1953.

>> Oh. That was right before the armistice was signed.

>> Huh?

>> That was before the armistice was signed in Korea.

>> Yeah, they were still in the war. Yeah, they were still in the war.

>> Mm-hmm. I … Wait. Why … Okay, so knowing that the war was still taking place, why would you volunteer?

>> That’s economics-wise because more work. I live in …

>> But …

>> I live in the island of Vieques. Vieques was small island and was a very, very poor island, and there wasn’t work to do. You would go to school, go away from school, and you can’t go to college because you don’t have the money to go to college, you don’t … You have … You find works and work around, so you have to go someplace. You either go to the state or either go to the army.

>> But that’s still different.

>> There was no choice.

>> But you’re still risking your life.

>> Well, yeah, but you have to survive. You’re looking for survival. That’s a positive.

>> Well, God must have blessed you so much because instead of sending you to war, he sent you to …

>> They sent me to Germany.

>> I know.

>> And I spend my whole time in Germany.

>> For how many years?

>> Almost 3 year. It was about 20 months, something like that. Almost 3 years I spent in Germany.

>> What was your service? What did you do in Germany?

>> I did infantry training.

>> Oh.

>> When they sent me to Germany, they check my MOS to Supply Specialist. They assign me to a supply company.

>> Actually, that’s very interesting. I like this interview a lot because most people think, “Okay, it’s war, so everybody goes to Korea,” but no.

>> No.

>> There were people serving in Germany, so right after World War II.

>> Yeah.

>> Not right after but soon after. There were people in other parts of the world, and they don’t realize that it takes a united effort to defend part of the army. So I’ve never … I haven’t really asked … I haven’t really heard from people who served during the Korean War in Germany, so can you tell us more about what it felt like being in Germany when you knew that a lot of people were fighting in Korea?

>> Well, in that year, in 1954 when I went to Germany, Germany was still under occupation. It was still in occupation for United States. So that’s what … We went as a occupation force. They still … United States was running Germany.

>> How many … How large was the unit or the people who were based there?

>> Well, I was assigned to the … I don’t know because they had so many bases in Germany, but this base that I was assigned was a supply company. All the part that the … All the vehicle, all the tank, all the … They need it there in Germany. They ship from the United States to Germany. I was stationed in [FOREIGN LANGUAGE], Germany. And so if they need a part anywhere in Asia or in Europe, instead of sending the part to the United States, they send the parts that are already in Germany. It was closer. It was a big, big, big, big supply, i think that supply is bigger than this down here, big supply. And then they had all kind of part in that supply.

>> Hmm.

>> So they don’t have to send something to the United States. If they need something for a tank or a truck or an airplane or something like that, they got them here.

>> Another question I always ask is, during the Korean War was when the army, military, was first integrated, right? Before it was segregated, and I ask many people what their experience in the military was like because even if the law said, “Okay, well, let’s” … “Puerto Ricans, they fought in a segregated unit.”

>> Yeah.

>> There was an all-Black army as well. So you were … Were you part of an integrated unit in Germany?

>> Yeah.

>> Did you face racism and …

>> No.

>> No?

>> No.

>> No?

>> No.

>> Really?

>> Really. When I was stationed in [FOREIGN LANGUAGE], no racism toward me.

>> Really? That’s …

>> I know that in United States, there was some kind of racism, racism, but none there. I talk about myself. I never was feeling that.

>> So other people in your unit, even if they were white Americans, they didn’t treat you badly?

>> No, mm-mm.

>> Wow.

>> Not in Germany.

>> That is actually a very encouraging thing to hear.

>> Yeah. Even when I … When my dad come to … When I wanted to enlist, I told them I don’t want to enlist. Even they … My company commander insists, [INAUDIBLE]. I said, “No. I don’t.” [INAUDIBLE] But I … Not in Germany.

>> So you left the service after 2 years?

>> Yeah.

>> And you came back to Saint Croix?

>> No, I was living in Puerto Rico at that time. I was drafted in Puerto Rico.

>> You were drafted in Puerto Rico?

>> Yeah.

>> What does that mean?

>> Well, they took me to the army, I was living in Puerto Rico. They take me to the army. I was living in Puerto Rico.

>> So you served in the army in Puerto Rico?

>> No, no, no, no, no, no. I took my training in Puerto Rico. They had training in Puerto Rico, and then when you take the training, they will ship you to the different place in the war. So when I completed my training, they shipped me to Germany. They ship some others to Korea.

>> Yes, but after, you could’ve come back home.

>> No, but my home wasn’t here. My home was Puerto Rico.

>> Oh.

>> Yeah, my home was Puerto Rico.

>> When did you come to Saint …

>> I was born in Puerto Rico. I was raised in Puerto Rico.

>> Oh, but you weren’t part of the 65th Infantry?

>> No, no, no, no, no. I was in the …

>> But you know about the Borinqueneers?

>> Yeah, I know about the Borinqueneers, yes. The Borinqueneers, yes, but I was not part of the Borinqueneers.

>> So when did you come to Saint Croix?

>> I come to Saint Croix … Let me tell you. My father moved here in 1952, and I came here in the same year, 1952. Then after that, 1953, I went to the army. When I came home from the army, I went back to school because when I went to army, I was only … I was in grade … was not high school. I had another 10 grades, so when I come home from the army, I went to fit in my high school. When I did my high school, I went to the state. I went to New York to live. And I stayed in New York until 1964, and that’s when I came to live here in Virgin Islands in 1964.

>> Wow. Do you still have family in Puerto Rico or here?

>> Yeah.

>> Both?

>> Yeah, yeah, both. And in the states, my daughters live in … I got two daughters and a son. My two daughters live in Jacksonville, Florida, and my son lives in New York.

>> Oh. Where in New York?

>> In the Bronx, New York.

>> Yeah. And you go visit them, huh?

>> Oh, yeah. I was there last year. And this year, I went to Jacksonville, Florida, to visit my daughters.

>> So between New York City, Saint Croix and Puerto Rico …

>> Puerto Rico, yeah.

>> … you like where best?

>> Well, I never complain about Saint Croix. I got no complaint about the state of what I was living in. Whenever I go, [INAUDIBLE] I don’t feel no homesick or anything like that.

– We were fighting in Korea. They’re doing a Korean Wonsan. The city’s infantry saved the American regiment. The Marine. For when the… came, they had to from Hungnam to… road. To go to the way because there were too many Chinese. They had to go the other way. They stopped the Chinese… the American gave into the war.

– Who fought in the, uhm, Hungnam evacuation?

– ¿A dónde?

– Fue que en el 50.

– ¿En el 50?

– …tuvo que agarrarle.

– En el 50 estaba allá.

– I went in 1951 until 1953. I went to the Geochang course. I go to different companies. I was the battalion company. Company I, second platoon, second squad. In Korea. Everynight… And I was the Army… with my company. Combat payment. Make the patrool everynight in Korea. Papas… She was my. Too much mine. Explosion.

– ¿Usted fue un policía militar?

– I was infantry over there.

– ¿Qué recuerda?

– ¿Qué recuerdo, qué recuerdo de allá? I was in the attack in… hills. Maybe you don’t remember.

– No.

– In Kelly mountain of Kelly hill. We fight over there in the mountain for three battalions. First battalion, second battalion and third battalion. First battalion about all the… battalion. Not all complete. Too much died. Killed. Too much killed over there in the mountain, and the second battalion, killed too. And the third battalion,… my captain said, “Two more dead, two more injuries.” So, we go to the mountain down.

– ¿Qué es el nombre de la batalla?

– Kelly hill. Three battalion. Right over there. – ¿Dónde?

– ¿Dónde fue esta batalla?

– En Corea.

– Sí, sí, sí, pero ¿el sur o no?

– I don’t remember the… You know. I was a debutant.

– Sí, sí, sí.

– In Kelly hill. The mountain is Kelly hill. The mountain.

– Korea Hills? Kelly?

– Kelly hill.

– Kelly hill. K-E-L-L-Y.

– Kelly hill.

– Kelly?

– K-E-L-L-Y.

– Kelly hills.

– Kelly hills.

– Yo estudiaré. ¿Sí?

– Sí, sí, sí. Y ¿qué, qué piensa usted de regimiento 65? De la legacía del 65.

– 65 pelió mucho allá en Corea y batalló mucho allá, mucho, batalló mucho.

– Muchísimo, ¿no?

– Mucho, muchísimo.

– ¿Por qué?

– I don’t know. The enemy took…

– ¿Cómo se llama? El terreno.

– Sí, sí, sí.

– El terreno. The mountain, the land, everything. The enemy took the…

– ¿Ustedes piensan que el general…?

– El general Cordero.

– ¿Qué?

– General Cordero nos metió allá.

– ¿Cordero?

– Cordero. Sí. General Cordero, eh…

– Three battalions. He make one… meeting in the yard over there. You can take the mountain in… You can take it. The mountain, the… You can take it. …the mountain. What? Okay. We go over there. No good. Too much dead. Too much injured. Too much killed. In the mountain, Kelly was the… Mongolian. Big one. The Mongolian and Chinese and Korean. North Korea stays over there too.

– Pero el regimiento fue segregado, ¿no?

– When we go back from the mountain the other day. We’re going to take the low weapon in the mountain. Too much weapon. And looking at the injured, the dead, too much people. Too much soldiers dead.

– Pero, pero el regimiento 65 solo, solo puertorriqueños, ¿no?

– Puertorriqueños, sí.

– Sí.

– Eh, después más tarde nos…

Attachment American soldiers in different company, Puerto Rico. Over there in Korea. The company… in different company attached the captain, the lieutenant to take out the…

– …eh, esto de, ¿cómo se llama? De que… los que… que venían de allá.

– Officer, American officer, attaching different companies. Attached my company, one American captain, I don’t remember now the name, he not believed me Puerto Rico. The American don’t believe me. The American captain don’t believe I’m Puerto Rico. When he go to the patrol and the scout take… the captain over here, this way. And the captain, I remember, because the captain said, “No, you have it the wrong way!” Company over here, this way. I don’t know. He walked to the patrol to the recognizant patrol, the enemy is approaching towards mine. I’m a soldier… Sergeant Rodríguez from… Puerto Rico. He exploded dead to the mine because the place is too much mine, you know? I remember the… I pictured it in my mind.

– Guao.

– Yeah, every…

[habla en coreano]

– Poema, un poema dedicado a las mamás de quienes tienen…

– Hijos.

– …hijos que participaron en la guerra.

– En la guerra.

– Sí.

– Sí. Ya.

– Anita me pidió que recitara esta poesía, yo se la regalé a ella y le voy a regalar también el libro que escribió mi mamá cuando yo estaba, eh, de poesías, ella escribió. Pero la primera poesía que está en este libro es la que dedicó a todas las madres que tenían los, los hijos en la guerra y esta se la dedico a mi querida nieta Anita con, de Corea de su abuelo boricua Josué.

– Gracias.

– Dice mi mamá de la siguiente manera, una plegaria que ella compuso en forma de poesía pidiéndole al Señor que preservara mi vida y que no permitiera que yo, con mi arma de reglamento, matara a ningún semejante y decía ella de la siguiente manera: “Señor, ¿qué te daré si me traes a mi hijo, Señor? Que se han llevado a la guerra maldita, aquel infierno. Señor, ¿qué te daré? Si nada tengo, pero tú eres bueno, Señor, y guardarás su vida. Señor, ¿qué te daré? Yo nada tengo que te pueda ofrecer por su pronto regreso. Señor, ¿qué te daré? Si mi alma está triste, muy triste, y nada soy y nada puedo. Por las noches, Señor, sin querer me desvelo, por el día, Señor, al infinito vuela mi pensamiento para pedirte, Señor, que cuides a mi hijo, que está lejos, muy lejos. Señor, yo le enseñé a mi hijo las sublimes palabras de tu santo evangelio, donde el amor nos une en vínculo perfecto, haciendo una familia de este gran universo, que los… Señor, eran sus hermanos buenos, la raza amarilla, los blancos y los negros, sin distinción ninguna, teníamos un padre bueno y ese padre, señor, eras tú, amante y sempiterno, que tú eras padre amoroso, sublime y tan tierno que, por salvar al mundo, enviaste de su gloria a Jesús, el, el Dios, el, el unigénito. Señor, se han llevado a mi hijo, a mi hijo, Señor, que es amante y muy bueno, para enseñarle, Señor, a matar a sus buenos hermanos de este gran universo. Señor, mira mi angustia y oye mi ruego, permite que mi hijo, Señor, que es tan bueno, no use su espada para matar a su hermano, el cual tú has hecho. Señor, permite que allí tú estés en medio de ellos, protégele sus vidas, pues, son tus hijos, cuida de ellos, en ti yo espero, únelos con tu amor inmenso y del campo de batalla, Señor, que salgan ellos para proclamar el amor de tu santo evangelio. Señor, yo te imploro que cuides a mi hijo y también te pido, Señor, que cuides de aquellos que dicen que son malos, pero yo no lo creo, ellos tienen sus madres, que llevan en sus pechos el amor de sus hijos y el corazón deshecho. Yo sé, Señor, que tú los amas como amas a los nuestros, son tus hijos, Señor, unos y otros, tú eres nuestro padre y padre de ellos. Señor, haz un milagro, yo nada te ofrezco, pues, nada tengo, pero, Señor, haz un milagro, trae la paz al universo, en cambio, las madres de este mundo te ofrecemos lavar, no ya tus pies, sino todo tu cuerpo con lágrimas cristalinas que salen a raudales de nuestros vellos. Dios les bendiga.

– Pero mis tíos fueron a pelear también y donde yo peleé, pelearon ellos, uno de ellos murió en mis brazos, lo enterré y regresé de nuevo, pero yo sé lo que es un hijo cuando está guerreando, cuando se manda a sitios a pelear, donde uno ha estado pasando… Y pasando malos tragos en la guerra. Así que yo también siento como padre y como hijo, siento como hijo porque sé lo que sintió mi madre, sintió mi padre cuando yo partí.

– No.

– Y nosotros, nosotros apreciamos todo el esfuerzo que hacen por nosotros, somos, fuimos soldados y somos soldados porque el soldado una vez sigue siendo soldado todavía, pero siempre hay alma.

– Sí.

. Hay agradecimiento y amor. Okay.

– Y gracias muchísimo, padre.

– And there’s a picture…

– Mi nombre es Carlos Josué González Mercado. Todo el mundo, las amistades y mi familia me dicen Josué porque mi papá se llamaba Carlos. Y antes de yo ir a Corea, trabajaba con la autoridad de Energía Eléctrica, y estaba a cargo del pueblo de Río Grande. En aquella época los pueblitos eran pequeños. Río Grande tenía 400 abogados y yo estaba solito a cargo de ese pueblo, pero empezó la guerra de Corea y, a pesar de que ya yo tenía 23 años, fui llamado obligadamente a servir en el ejército de los Estados Unidos. Recibimos entrenamiento en el campamento de Tortuguero en Vega Baja. Y a los 3 meses de recibir el entrenamiento zarpamos para Corea en un barco que se llamaba Sargent… Viajamos de aquí a Panamá. Cruzamos el Canal de Panamá. Llegamos a California. De California seguimos a Hawái. De Hawái llegamos a Japón. De Japón definitivamente llegamos a Corea un mes después. Salimos de aquí viernes santo de 1951. En Corea me asignaron al 65 de infantería como uno de los primeros refuerzos que fueron al 65. Había otros tres regimientos americanos, dos regimientos más americanos. Era el 7 y el 15, pero el único regimiento que era de puertorriqueños solamente era 65. Era un regimiento segregado de solamente puertorriqueños. Bien, naturalmente, nos unificó más como pueblo, como amigos, como compañeros, porque al fallecer uno nos dolía a todos. Y fue un año completo en que estuvo en la guerra de Corea. Si ustedes me permiten dar un testimonio de la grandeza del Señor. Mi mamá, cuando yo fui a Corea, hizo una plegaria pidiéndole al señor que no permitiera que yo con mi arma de reglamento matara a ningún semejante mío, una petición que para cualquiera es imposible porque a nosotros nos adiestraron para matar, para matar gente, y pedirle a Dios que un hombre que lo mandan a matar gente no mate a nadie eso es una escala muy alta. Ella también le pidió que preservara mi vida. Y durante ese año que yo estuve en Corea, al yo llegar, perdóname, al yo llegar a Corea, el comandante de la compañía donde yo estaba, vio mi récord y decía que yo era lineman, procurador de líneas, que tiraba líneas, conectaba teléfonos, y hacía instalaciones, y hacía bregar con los switchmodes. Y dijo al sargento: “Este es el hombre que necesitamos para conectar los teléfonos de la compañía de regimiento”. Y mi trabajo en Corea, donde un año, por un año fue conectar teléfonos y operar swichtmodes. Por lo tanto, mi mamá no puede testificar si yo maté a nadie, pero yo sí puedo testificar eso porque debido a ese trabajo que tenía, de mi rifle no salió ni un solo tiro, o sea que no pude haber matado a nadie. Y hay que darle gracias a Dios. Por esa oración de mi mamá que le pidió a Dios eso, y Dios oye a los corazones contritos y humillados que se doblegan ante… Por eso yo donde quiera que voy, y me preguntan, doy mi testimonio de la grandeza de Dios que me permitió regresar con vida sin tener que matar a nadie y servir en el ejército sin tener que cometer ese roll.

– Sí.

– Dios me los bendiga.

– Sí, sí. Gracias, gracias… Su Abuelo es un pastor, ¿no?

– Mi papá.

– Papá. Yo también.

– Este es mi papá, mi mamá, 9 hermanos.

– Oh, my God! 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9?

– We were 10, but one died very old.

– Where are you?

– I am the 3rd one. That’s the oldest, 2nd and the 3rd. This is 4th, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

– Wow, bueno, el señor da a su familia muchos, muchos…

– Todos, toda la familia sirve al señor, toda la familia. Mi papá y mi mamá nos enseñaron a amar a Cristo por…

– Gracias.

– Esta fotografía fue tomada cuando mi papá y mi mamá cumplieron 60 años de casados.

– Wow, 60 años. Gracias muchísimo.

– Dios la bendiga.

[HABLAN EN COREANO].

Thank you.

[HABLAN EN COREANO].

– …

[HABLAN EN COREANO].

– Which battle did you fight?

– … una pelea, ¿verdad? Estaba encargado solamente de…

– No, no.

– My name is Carlos Pena Lozano. Okay. I went to Korea in 1951. I landed in Incheon through Yokohama on a small boat. We have sweet water at [—-] and saltwater. And we were to Incheon. The port of Incheon was in flames. I was a kid. 17 years old. I guess most of the kids in this island joined the army on those days because [—-], and it was showed to the world. So we went to the [—-], up on the mountains. I got wounded there. I shot two times. I [—-] the [—] river, and we got frozen. [—-] the Chinese. And you know, they started firing at us and everybody ran. But after that, a few months later, I was shot in [—-]. They said I was dead because I dropped in a creek, a frozen creek. The next day, a Korean peasant saw me and I was almost dead. They took me on a helicopter to Gimpo, to our base. I found out later that the Puerto Ricans operated me, and from there on, I was sent to Japan for recovery and to the States. Later on I ended up on Panama, and I got discharged.

– I heard that you went back to Korea last year.

– Oh, yes. Yes. I would like to thank the people of Korea, the government, all the people there that treated us like, you know… I don’t know if we deserve that kind of treatment. Even my wife cried the day all those Korean officials came to greet us, and I was never treated better in my life anywhere like in South Korea. People are marvelous. I guess [—-].

– Well, you should’ve been treated like that, because we, the Korean people, are here because you fought there, you know? I wouldn’t be here if you didn’t fight there.

– I’d also like to thank [—-], real Korean people that, you know… [—–]. We never had that recognition we had, you know.

– Well, you should be proud.

– Oh, yes, I was proud that I went to South Korea and I met nice people.

– Thank you so much.

– I guess everybody in the 65th infantry regiment have all the Koreans in our hearts. Yes.

– Thank you. That’s so sweet.

– The first thing that comes to mind.

– The people. The people.

– And what kind of people are they?

– Fantastic. They are nice people. Nice, nice. I guess that every time that I travel and go anywhere, people would do… [——] in South Korea. I’m talking for all the Puerto Ricans that have gone there, and I guess everybody that’d been there, so it’s your people. Really good.

– 2004, ¿no?

– Un poco…

– Más alto.

– Sí.

-Doménico Adorno.

– Sí, cuando, cuando, ¿participaron en la guerra?

– Nací en el pueblo de Trujillo Alto. A los 21 años fui reclutado por el ejército. Me enviaron a su país, Corea. No tengo buenos recuerdos. LO que tengo es un sentimiento porque muchos han ido ahora y dicen que Corea está muy pero muy alertada, muy avanzada, pero todavía en mi vida no capto, todavía yo tengo a Corea de 66 años atrás. Yo estuve en Chon todo el tiempo. Estuve en una oficina del tercer batallón. La oficina pertenecía al 65 de infantería. Estaba localizada en una universidad que había sido destruida por los americanos para sacar al enemigo, a los coreanos… metidos. Tuvieron que bombardear ese edificio. En ese edificio había partes que se podían usar, y ahí estaba yo en una oficina. Yo estuve 13 meses, un año y un mes. Mi trabajo allí era que me enviaban el informe, informe todas las mañanas de los muertos, de los desaparecidos, de los heridos durante la noche del cuerpo del 65 de infantería. Había mucho conocido mío. Todos eran puertorriqueños. Para mí era un dolor, aunque no los conociera físicamente, pero eran mis compatriotas. Eso es un dolor que llevo, ¿entiendes? Porque todavía conozco descendientes, descendientes de esos muchachos que perdieron la vida allí. Cada vez que los veo me traslado a Corea. Esa es la parte primordial del viaje a Corea. Bien, tengo otros recuerdos mucho más tristes del pueblo coreano.

– ¿Visitó a Corea el año pasado?

– No.

– ¿No?

– No, voy a visitarla.

– ¿Vas, vas visitar el mes de septiembre?

– Sí.

– Ah, ¡ok! Sí.

– Pues aquel tiempo ustedes no habían nacido.

– Sí, sí, sí.

– Fue un tiempo triste para Corea. La guerra destruyó la manufactura, destruyó la agricultura, y Corea vive… de la agricultura, de la pesca, bueno. Recuerdo, por la tarde cuando yo salía de la oficina, se había todo empolvado porque los edificios son hechos de un material, no recuerdo ahora, que es como tiza. Salía afuera. Había un, una reja para no entrar al edificio donde estaba la oficina. Nosotros pegábamos allí… y eso… triste ver cómo las mamás…

[HABLAN EN COREANO].

– Sí, sí, sí.

– Lloraban pidiendo comida, y muchas veces hacían cosas indebidas, cosas indebidas con sus hijos. Yo tengo mis hijas ahora, mi nieta, y eso me lleva, ver un pueblo destruido físicamente…

– Sí.

– Y moralmente.

– Sí, pero ahora es muy…

– Eso es distinto, pero yo no lo he visto.

– Sí. Gracias.

– My name is Domingo Pelliciel. I was in Korea in 1951.

– Look at me, look at me.

– Not the camera? Oka, my name is Domingo Pelliciel Febles, and I was in Korea in 1951. When I went to Korea I was 21 years old. We landed in Incheon. In Incheon, the ship [—-] stayed out the [—-], and then we go out through [—-], down to the small landing boat to the shore. From there, we went into the train. That train had [——]. There were two trains, one go in front and one in the back. So we went to Seoul. From Seoul we went to the frontline. [—-]. I was witrh the 63rd infantry regiment [—-], rifle man. And in Korea, I thought that was in the end of my life. I was in combat over there, with the infantry, and [—-], one time I was on patrol, and then the American airplane was bombing the Chinese, and then they thought that we were North Korean or Chinese, and they came to us. To bomb us. So I have a piece of cloth. This color. Yellow. And red. So the captain said, “Open the cloth.” So I opened it and the plane went out, because that showed that we were friendly, we were no enemy. So they went out. Another time, while I was in Korea, I was on [——], I saw a lot of people moving in the back, but to [—-], so I took a hand grenade to throw the hand grenade, and behind me there was a piece of… maybe a tree, and it my hand. So they hand grenade went out, so [—-] in the hole, so I jumped inside the hole. I jump, and then… If I stay up, my face would’ve disappeared from my body. One time, I was doing a hole up on the hill, and then, when I was doing the hole, there was snow, and the snow jumped, and the Chinese… I don’t know if they were Chinese or North Korean, they were watching me with binoculars. And then… I hear the mortar come to me, and I started to run so I go in the ground and start rolling like a boulder down the hill, so thank God. If I stayed up, they’d keep shooting me, but when they see me falling through the ground they stopped shooting. One time also I was with my friend, who was laying a barbed wire, and then the wire hit the fray, when you hit the fray it lights up, and the wire hit the fray, and the Chinese, Chinese or North Korean, I don’t know, they were looking and started shooting with the mortar, and my friend was wounded in the back. So thank God there was a hole in front of me. I jumped in the hole and they shoot my friend like 3 or 4 times. My friend was my Corporal. He was with a Korean soldier, a Korean company. They called it rock, right? Yeah, with a Korean company. So we had to translate from Korean to English, so we had Korean in the company.

– You remember his name?

– [—–].

– Amazing that you can remember them. Did you ever meet them?

– No, no.

– Maybe…You’re going to go to Korea next month, maybe you could find them.

– Maybe I find them. Maybe they’re dead right now. Maybe. who knows.

– No, maybe not!

– It was many years ago. It was 1951.

– That would be wonderful if you could find them.

– One time we were on patrol, and we walked, walked, walked, walked, and then the guy said, “[—-] we have to find the company. Please go back to the company.” So the… I’ll say the enemy, because I don’t know if they were Korean or Chinese. They were waiting for us. So this is the gate. we’re walking, so we stop over here and we say, “let’s go back.” and they started shooting with machine guns. They’re waiting for us to be right in front of the machine gun to start shooting.

– Did you get wounded?

– No, thank God I didn’t. Thank God, because my mother was praying for me. She was praying to Virgin Mary and Jesus. To Jesus. Saint Jesus. I went to Laos…

– GRACIAS A DIOS…

– They’re shooting, but I came out alive. Also, when I was on patrol, we used to see a little paper with [—-] propaganda, propaganda like writing in the paper, and the paper said [—-], “Go back to your country. Your family is waiting for you. Leave Korea for the Koreans.” In the paper. I used to look at the paper and say, “Oh, my God.” They have a soldier dead on top of the barbed wire. [—], “down.” but, forget about that.

– I’m so excited you’re going to get to go to Korea for the first time, right?

– When, now?

– Next month.

– No, second time, because I was there.

– Oh, second time!

– No, no. First time I was in combat.

– Oh, yes!

– Now I go for pleasure.

– Yes. I’m excited for you.

– I go for pleasure, for that time I was in combat.

– I’m so excited. Maybe I can meet you there.

– Oh, I hope so. I hope so.

– Yeah. Okay. What do you want to say when you go to Korea?

– Thank you, Koreans. Thank you.

– No! We thank you!

– Oh, yeah. Me too, me too.

– Why?

– You say it to me, I say it to you too.

– You don’t have to thank Koreans.

– No?

– No. We thank you, right?

– Well I say welcome. You’re welcome. You know, i was in Korea, I was in the hospital, in [—], in the hospital. From the frontline I went to sea, and they put me in the hospital, and the nurse was Korean. She shaved me, washed my face, my arms. Then [—], I keep sick, so they sent me to Busan.

– Swedish Field Hospital.

– Yeah.

– You went to Swedish Field hospital?

– There was a ship, a big ship.

– Yolandia.

– Yeah. In Busan. How do you say, Busa or Busan?

– Busa.

– We say Busan.

– Busa. You went to Yolandia, the ship?

– Yeah, I think so.

– Cool. I went…

– It was a big ship. [—-].

– I visited the Danish veterans.

– Oh, yeah?

– Yes.

– But that was their ship?

– Yes, Yolandia.

– Yeah. It was in the port of Busan. Right there. So I stayed there for one week, a couple of days, then they sent me back to the frontline.

– GRACIAS A DIOS, GRACIAS A DIOS ESTOY PORQUE DIOS LO QUISO ASÍ.

– Thank you. I pray that you will continue to have a lot of…

– Also, I have a friend of mine, rest in peace, his name was Pedro [—], from Puerto Rico. He was in Korea for 13 months. They told him, “You go back to Puerto Rico.” in for days. So one night we had to go on combat patrol, on combat. And then he said to the captain – the captain was American – “I’ve been here in Korea for 13 months. You [—-] the company, so I can go back home.” He said, “I don’t care how much time you’ve been in Korea, you have to go to fight. You’ll stay in the company.” And we went to combat, and he was killed. One bullet in the chest.

– Well, thank you so much. I’m so glad you are not…

[HABLA EN ALEMÁN].

– English.

– Okay, this [inaudible] says, “Welcome to the 65th Infantry Regiment.” This insignia here [inaudible]. [Inaudible] everybody, because the Puerto Ricans, our 65th infantry was [inaudible], and it’s still commemorated for the Korean War. And let me tell you, I talked [—–]. After 50 years, I went back to Korea, and I was so happy, because Korea today looks so [——]. [inaudible]. [inaudible[, and are waiting for people to remember us and talk about the 65th infantry regiment. It was amazing. I feel so good we have this display here. [inaudible]. It is me. And I’m proud to be a Korean veteran. And to the Korean people, Salaam-Alaikum. [Inaudible].

– … of us, you know. We’re so grateful to you as well, you know? I’m so happy you said that we [—–].

– God bless.

– Thank you.

– Anita?

– Anita, my granddaughter.

– ANITA. SÍ, SÍ, ANITA, SU NIETA.

– MI NIETA.

– SÍ.

– COREANA.

– SÍ.

– QUÉ BUENO.

– So, snow… I have, because [inaudible] in the United States, but we had two enemies. The enemy and also the snow, because it was really, really cold, and some of our men had to be amputated, because they got gangrene for the cold. And I tell you, it was terrible. But we made it, and, some of them… we have the man in Puerto Rico, who’s half maim. We had to amputate his legs.

– Frost bite.

– Frost bite, yeah.

– How many died, how many were killed in action?

– Wow. Too many.

– 70%.

– 70%?

– 17.

– 70. 7 – 0. 70% of the Puerto Rican heroes were killed in action.

– 70?

– 7- 0.

– My uncle, which was a soldier with the 65th infantry.

– How many…?

– I’ll look it up.

– 70%.

– But the round number… 70%.

– The funny thing is about my uncle, we never found out what happened to him, because…

– He’s MIA?

– I don’t know if he was a prisoner of war, but we never found his body.

– So he’s missing in action.

– Of course. As I already said, I’m going to dedicate my life for our veterans, because I miss my uncle.

– The records’ keeping at that time, remember…

– I know.

– There was a language barrier.

– I know.

– So… and there was a war going on.

– And there aren’t…

– So records got lost.

– And because the war hasn’t ended, you know, it’s difficult to identify the remains, or retrieve the remains. And so there are 8000 MIAs, POW in Korea, which is… you know…

– There might be some alive, but I doubt it, cause it’s such a long time. But I hope one day… they’ll return all these people to us. [—-].

– It’s something that’s very dear to my heart, so… Because the families will never know what happened to them.

– No closure.

– Yeah, no closure.

-Okay, my name is Thomas Lopez. I’m Puerto Rican, of course, and I’m part of the 65th infantry regiment. And let me tell you, they call me a hero, because [—-] the 65th infantry complete. [—-], because [—-] in Puerto Rico, they sent me some kind of… like a plaque, considering me a hero. It was not only Tommy Lopez, it was all the 65th infantry, represented. And when I went to Korea of course I’m going to talk about the cold, because it was really… the Puerto Rican, we’re not used to that kind of weather, and we had two enemies. The enemy and also the cold. And as a matter of fact, we have people, as I told you before, that became… A man in Puerto Rico that was half a man, because we had to amputate his whole legs. And a lot of them suffered the cold. [—-] being an infantry man, because we had to communicate in English, in Spanish. They sent me to school in Seoul, and I learned communications in Korea, and when I went back, I was [——-] for the big, big, big [—-] in charge of the 65th infantry regiment in Korea. And that made me feel so proud. But I’ll never forget those who still were fighting in Korea, because they were my people, and as A Puerto Rican I love [—-]. And thank you, thanks to you, Anita, because you make me feel so good, so happy. I wish you to continue learning with the 65th infantry, because we have to recognize [—-]. Personal recognition to Anita [….], thank you so very much. God bless. Okay, first of all, we should go up to the schools and teach our kids about the 65th Borinqueneers. A lot of people don’t ever recognize, no, when we’re in Korea, and in this personal memories that I still have should be distributed within the kids, to have an idea what it is to defend this great country, which is America. It’s my country too. I was born in Puerto Rico, but I became a citizen. When I was born in 1917, it was tough to be citizen, because we used to belong to Spain, and when they came to… the war between America and the other countries, we became citizens. [——] made us citizens. So I’ve been a citizen all of my life, since I was small, that’s right. But there’s one thing I’ll say. There was a smart kid [—–] and lifting the flag. There’s the [—-] reason the Puerto Rican flag, and wherever place I go, I make sure I take my flag too, because it represents the 65th infantry, the Borinqueneers. And this is why I want the kids to learn and to know the history, and love this great country. First, I’ll say thank you to the Korean people, because I love you. And also, such a big change made me feel so proud and so clean about Korea. The people dress so nice, everybody, [—-] people. And of course, [—-] before, we did the other… [—] and many evangelistic churches, and we’re happy we had a chance to some of them. [—–] was so happy that we were there.

– Well, you deserve to be treated like kings.

– Thank you.

– Hi, thank you, Hannah. Yeah, so, the 65th infantry regiment of Puerto Rico fought in every major campaign of the United States wars, from World War I to World War II and Korea. But they distinguished themselves during the Korean conflict. The Korean conflict was 3 years. The Puerto Rican regiment was a regiment sized military unit. So, they fought in 9 major campaigns, from the battle of the chosen reservoir, where they were the frozen chosen, to the evacuation of Hungnam, and most famously was the bayonet charge of February 2nd, in 1951, where 2 battalions of the regiment encountered the Chinese 149th division. Now, a division is made up of 10,000 men, and a battalion is made up of approximately 1,000 men. So, there are your contrasts. So the numbers were basically, you know, 10 to 1, right? 100 to 1. So they fought valiantly for 3 days. They fought so valiantly, that the order came down to fix… the order came back to fix – the memories came back – the order came back to fix bayonets. The bayonet was fixed to their rifles. The order was given to charge, and they fought almost basically hand to hand in a very ferocious battle. As the culmination of that battle, there was the sound of a bugle. The bugle sounded withdrawal. It was the sound of the Chinese bugle, which called their units to withdraw. Now, there were 7% casualties. They left no men behind. They brought back all of their wounded. They brought back the story of what occurred to their commanders, the commanders brought that back to us, and now we bring that story back to you. So, as a culmination of that distinction, that gallantry in the field of battle that even the enemy had to bow in respect to this kind of worthy opponent. So it took us approximately 65 years to bring attention to… the military, where they had to prove themselves, they had to contend not only with the elements and with [—-], but with a ferocious enemy. They proved themselves time and again in their ingenuity, in their gallantry, in their bravery in battle. And then even after such, here, 65 years later, I gather together the remnant of these veterans to be in the 65th infantry on a task force, to help educate the public, help educate the congress, to help bring attention to their magnificent story to the American landscape, which culminated in the award of the Congressional Gold Medal, which is the highest award that the people to the United States can give any military unit. and in their gratitude as well, the people of Korea, and the government of Korea, awarded each of the Korean veterans this friendship medal, and also the Ambassador for Peace medal, so…

– Smile! Look here!

– I’m your master of ceremonies during this event. We gather here today to present a flower wreath in honor and gratitude by… to the fallen soldiers of the Korean War buried and memorized in this cemetery, and to thanks the family members for their sacrifice. Please, stand up if you can. For the… in honor of our fallen heroes.

Please, be seated. We would like to thank the presence of Mr Glenn Power, deputy undersecretary of the. President of the Korean-American association of Puerto Rico. Member of the Remember 727 Organization for Korean War Veterans. Ms… President of 65th Infantry veterans. Member of the 65th Infantry divisions were engineers, family members. And now we have Mr. …. director of the Puerto Rican National Cemetery with a short message.

– I’m going to… I didn’t know I had to give a short message. But another things, uh, thanks him for actually taking time and making this possible. I’m very proud of the 65th Infantry … for their service in Korea, World War II and other places. They went to Panama, all the places that they served. And I was just talking to Mr. Glenn Powers about how all this as a society in Puerto Rico. We don’t give the honor to our servicemen. So, I think today with this short, small ceremony, we are honoring our Korean veterans and all that… year. And, also, the veterans that we have here and… all our respect. Thank you for being here. Thank you for what you’re doing. And welcome to our cemetery.

– Now we have Ms. Hannah Y Kim, member of the 727 Organization for Korean War Veterans.

– Gracias muchísimo, ah, por su hospitalidad y su dedicación de, para mis abuelitos. Yo soy, yo me alegro muchísimo porque yo estoy aquí porque ustedes fueron allí en Corea y yo estoy aquí con ustedes y mis abuelitos, quienes pasaron sacrificios últimos. Y no solo estoy aquí, estoy aquí con todos los coreanos, como presidente lee y representante de corea, porque no, ellos no pueden, ellos no pueden venir aquí, sí, y por eso yo estoy aquí para decir a ustedes gracias muchísimo, para todos. Y nosotros, coreanos americanos, como yo, y coreanos en Corea y coreanos en todo el mundo, nosotros disfrutamos libertad porque ustedes fueron en Corea y nosotros nunca, nunca olvidaremos. Gracias muchísimo, gracias, Javier, y gracias muchísimo.

– …and Mr. Javier Morales… Mr… to honor with your presence and… To place the flower wreath in honor to our… in the Korean War.

– …mis abuelitos. Gracias.

– Pueden ir todos, por favor.

– Sí.

– I… War… of the island. I joined the army when I was 23 years old. That time, I had my training here in Puerto Rico and I was in all the places throughout the island serving on the World War II. There… Puerto Rico to South Africa, North Africa and then to Germany. In the… there wasn’t so much to do there, just clean pockets of the Germans. You know? Germans… clean the pockets of. From there I return to the island, then I, uh, I was out of the army. Then I went to study because before I had only eighth grade… the country. And the… I coursed my high school in another town in the center of the island called Barranquitas, … I had my high school diploma and then I moved to the nearest city of Puerto Rico. From there, I graduated and I went to the, to teach in Puerto Rican schools of Puerto Rico. But since then, I have my sedentary done and then out of… They happen to be I didn’t know about, but I was in the reserve when this… 1996 went to Korea. I was called into the field. I was sent to Korea. So, there, I fought in Korea. I was wounded in Korea. I returned to the streets and I was… help because… and I was sent to Germany to serve for 23 years. I was sent to… I served there one year. At that time, I had two sons, they were out of the… same place they died there. That’s the only thing that I will regret all my life. So, I know what the father and mother know and think about their son going to war. So, I went to war and my father said, “It’s time to war”. So, that’s life, what can I say? I am grateful to God, grateful to people that are around me now. People that are… there… Right now I’m 95-and-a-half years old and I still…

My only daughter died two months ago. One month back. And she comes here to be buried here. Today and talk to people here… So, I’m glad I don’t die. I don’t want to die, but… in the… another time… somebody will follow you. I’m very grateful, and thank you, people, for being here and taking care of us, and say hello to us and appreciate what we did in Korea. You probably know that… Korea… What I saw there and the people there. What the people did to us, I appreciate it very much. …and to people… not only myself, we were 19 of us, right? And we appreciate it… Korea. We appreciate that. Thank you again. I went to the country, how it was. Wartime. Everything destroyed. Very dead people. People dying by me. Many things. Very hard for me to tell, very hard to me to tell things like that. It’s another fight. No, no. The only thing I remember was I was there in … And walked all the way down to Seoul. And we fought and that was it. Until I was wounded and taken to home. I had no time to see the country or talk to the people in the country, meet the people in the country, nothing whatsoever. Which now I am very happy to… know the people. The Korean people now. I really appreciate it. And to say to other people what the Korean people were at that time and the way they did… Korea… this today. It’s very different. Very different. But I…

– Do you remember the name of the battle?

– No, we didn’t have time to that. We fought all the way through and the enemy was upon us. Nothing done. You’re fighting, fire. That was that. Bad. Terrible. I say that there should be no wars. Because everything… When there is a war, everything is destroyed. Including the people. Everything is destroyed. The city. The… Everything is destroyed. I hope… our island Puerto Rico for United States. I want to be clear…

– You too?

– I thank the Korean people, because when I visited there, the way they treated me or the people that went there. Good. Nice. And they showed us the way Korean is today… The country of Korea is today… Nothing… So, I, uh… I feel that when I lived in Korea. Little… The people of Korea… for Korea…

– To the cemetery,

what would you think?

– I want to tell you something.

… what I say. I’m going

to tell you something, you know.

– Okay.

– I joined the Army in 1940.

I was 17 years old.

I trained in Tortuguero, Puerto Rico.

Then went to Fort Neal, West Virginia.

From Virginia, we went to North Africa.

And so we headed. We landed there

with 40 dead because we had a kennel.

Because we had a coronel who don’t believe

that puertoricans were their friends.

He went there and kill it… Somebody killed it.

I said everyone in North Africa, they all went to,

uhm… Germany.

Yeah, and I always tell

… about 10.000 prisoners.

… The coronel called, he used to be a commander.

So I came back to Puerto Rico and stayed here.

Then, they planned the work, the maneuver…

Porter maneuver to certificate

that it was the best way to…

That’s what they said, to Korea…

They fought everything. so, myself was

the driver of Mayor General Harris,

so we left him in here, in Puerto Rico.

1950… December, 1950. So we went

in the Marine links, about 16.000 soldiers.

so we land in Busan. So, at the next day, we …

fight in the front, so I used to be the driver

and bodyguard from Coronel Harris.

So, I had a… with Coronel Harris.

So, one day, General McArthur stopped us himself

and he told to General Harris,

“you have to go to that hill

and throw the people in there.”

I remember that.

And General Harris said,

“no, my people has to come back to me, now.

They’re going to rest.”

So, I thought, uhm… He was, you know,

disobeying an order from a Mayor, a General,

he was a Coronel. So, well he left him over there,

So, I know we have a hook for,… in spanish and english.

So, we have everything that the guys have said.

That’s to believe. Because I spente 11 moths in there

with the Coronel and a mission… heave, we go.

I never really thought…

The day the guy walked in the kitchen,

the Admiral used to chew for…

And in the showers, the showers came down from the hill.

We didn’t know it came from the hill.

He said “my girl is washing there, so…”

So, I went down… three pieces of…, you know,

because I knew everything was alright.

The ’65 is one of the best in the world

I know, because I used to be the driver

for Mayor Coronel Harris. We sailed in maneuver.

We were five rocks from…

Then we left for…

And one of the guys said “load the arms”

and one guy from my hometown, they got a .45.

And when you load the .45, it fires a shot…

General Cordero, he was a volunteer for…

And that’s the way, if you are very sick…

I really think so, because the puertorican who

sailed there,… sleeping back, about 20 degrees.

Also, in North Africa, … we slept in there,

the valley… at 32 degrees.

We had to go to the river,

That’s the way…

I used to go with General Harris,

I uses to be the driver.

– But what do you remember?

– I remember the day.

– What did you feel?

– One day, he went to… We were below that,

everything, we didn’t know that they were hiding.

And one morning we called, so they came down

when we started the kitchen, you know, boiling eggs, the breakfast.

And they called out:

“Everybody! I have a job for our company,

every one of you have to kill seven guys.”

– Oh.

– Wow.

– That’s all I have to say. My brother,

he was a policeman, he.

So, we had so many points and they gave me

the break and sent me first.

Yeah, because, I mean…

The korean, yeah. We fought along that people,

you know, together. And they did.

They had this little sack and that’s where.

– Did you volunteer to fight for Korea?

– No, because I used to be a driver

for the Army, Fort Maneuver.

– Yeah, but did you volunteer to be the driver?

– Yeah.

– Volunteer?

– Yeah.

– Why? Why.

– Because I said “fine”, a day that I went to…

No, I forgot the General, to drive to Korea.

they said four days, and they selected me

to be the driver.

They were looking for a man to follow him,

the General.

Well, I’m telling you,

the worst would be the war.

Because I had to be the devil or the saint.

For example, I’m in Puerto Rico, what happens now?

They say I can’t walk, you know why?

Because that guy up there, he sees everything.

I’m alive because my mother,

she promised for me three times.

Three times. I’m alive because of her.

Look, …

but that one is the one that kept me alive.

Don’t worry. I’m 93 years old. Suffer? Suffer.

– The south korean people. Message.

– Korean people.

The korean people were, for me, the best people in the world.

Because I was with them, fought beside them.

We went over there, they were over there.

They give everything that people,

I remember that.

The people that were over there were…

I’d like to go back over there,

because they treat puertoricans like.

A friend of mine, he went.

– …Cardónez. About the battles in Korea, I only remember that I was a lifer man, I was, all the time– Most of the times in different lines. When we arrived in Korea with the 63rd Infantry, that was the 6th battalion of the Infantry regiment. And we arrived in Korea on 1 October 1950. So we started going in patrols, because by that time [inaudible] elements, and probably the worst one when China came into the war. There were too many Chinese for us. And I remember that we were, I mean, the first division in the U.S., it was in the [inaudible] war. Is that right?

– Yes.

– So it was November, 1950 when China entered into the war, and the first thing they were trying to do was to finish with the Marines that were taking care of the reservoirs. So, it was winter, 1950. The water was up here, about our knees, and the Chines almost destroyed the Marine division, and the 63rd Infantry were holding the Chinese to help the Marines get out of the– and go to the port of [inaudible] in Korea. So…

– And you were part of that?

– Yeah. The 65th Infantry regiment was the last unit left in North Korea during the US [inaudible] in 1950, and — when we got into the ships that were about 15 or 20 miles in the sea, our regiment put a lot of dynamite in the port, and as soon as we left, they destroyed the [inaudible] in order for the Chinese to use any– for the moment. We were taking to Pusan– everybody was taking to Pusan. And– it was– we went into the ships, it was on 24 December 1950, Christmas time. And we had– they gave us supper on the ship, so we’ve been more– removing our clothes, and when we’re taking into the ships, we were ordered to take our clothes, and they gave us clean ones, clean clothing. So, after taking us to Pusan, they assigned us positions 12 or 15 miles at the North of Pusan. The January 1, 1951, I was assigned to this [inaudible] the 3rd Infantry division. When I stayed for 6 months– July, the same year, I think, 1951, I went back to my company, the Infantry division which was in the front. So, in September, 1951, we were attacking the hill at the west of Ch’orwon, there are hills at the west of Ch’orwon. Ch’orwon is about 20 miles from the parallel, up. And– with the [inaudible], the Chinese were all around, and they were attacking us with urgent. And it was raining like hell. It was in September. And I was trying to– we received orders to leave the place. I was assigned [inaudible] one of that. I don’t think the North Koreans are [inaudible]

– On 18 September 1951, we were capturing one of the hills. As I told you, it was raining like hell, and the artillery, the Chinese artillery all the time, and we were ordered to go back and leave our place. So, there were 12 comrades there already, and I was assigned to carry one of them out. When I was taking care of my comrade, I was hit in the back by Chinese artillery, and I have to leave him, to leave the dead man I was carrying. So, I was taken back to the line, to the resting line, and I was taken to some doctor, and — by that time, I had spent almost 14 months in Korea. And I never went back to the front line. They continued to [inaudible] to take me out of the front lines. So, I entered the Army for three years to volunteer. I can tell you that when I graduated from High-school in my hometown, I entered to work in a drugstore. And on 20 June 1950, I entered to volunteer in the Army to study for officer at the canals in Panama. Five days later, the North Korea, at that time, South Korea, and we were sent to the canal zone, and it was basic training. And when we finished the training, the company commander asked me that they wanted me to stay at the pharmacy in Panama, and I said, “No, I want to go with the Japanese.” So I went volunteering to Korea. I went volunteering in the Army, and volunteering to Korea.

– Why?

– Because at that time, I was 20 years old, and I liked adventures, I liked risky scenes.

– But you could’ve risked your life.

– That was something included in the package. So, I studied three years in the Army, and– get my [inaudible] studying at the University of Puerto Rico. I worked for the government for 23 years, and at the four years studying makes 27, and three years in the Army makes 30. “It’s time to get out of the government.” So, in 1881, I had been working by myself as a lawyer.

– Yes. One more question because you said that you wanted to risk your life for adventure, and you could die. But here, you’re at the cemetery, with comrades who did die. What do you think when you come here?

– Well, we come here because we’re alive to honor them with our visit here. And we do the best we can to have this place as it is.

– Are you glad that you didn’t die, though? I am, I’m glad.

– I’m glad. I’m glad I’m alive. And I– when I saw Korea last September, it was like a miracle because– Korea was all destroyed, and now they have this beautiful country, beautiful Seoul, the capital. And nice people everywhere and I’d like to do there again. Sometime, I will.

– Soon.

– It was nice to have you here, and I hope you enjoy your stay in Puerto Rico.

– Thank you so much.

[ININTELIGIBLE]

– My name is Javier Angel Morales. I am the past president of the 65th Infantry Veterans Association. I served for about 5 years. Our organization [inaudible]. And they were the ones who organized this whole association in 1936. At one time we had numbers of about 500 members. Now they only have about 150. They had to open up the association to allow veterans from other conflicts or wars to become members, because we want to continue the legacy that the 65th infantry gave to Puerto Rico. As to the Borinqueneers, there was a voluntary army, first [—] in 1917. They were all voluntary. They didn’t have to be drafted. The draft came in World War II. After World War II then came Korea. During the Korean War there were a lot of draftees. I could relate to some of the stories given to me by the different veterans, who were in smaller towns, but when they heard that there was a truck coming picking up those that would like to join the service, they jumped on the truck and were taken to [—-]. Some of them… one person told me that it was the fourth time he was trying to get in the truck, but they turned him down because his age was not the legal age to be drafted. [inaudible]. The regiment was composed of veterans that were from World War I and II. They had been volunteers and they were ready to retire, but they were asked to stay so they could train the new recruits, so most of them did that. That’s why I think the regiment was so…

– Experienced?

– So experienced during the first years of the war, that they were labeled [—-].

– How many served and how many suffered [—-]?

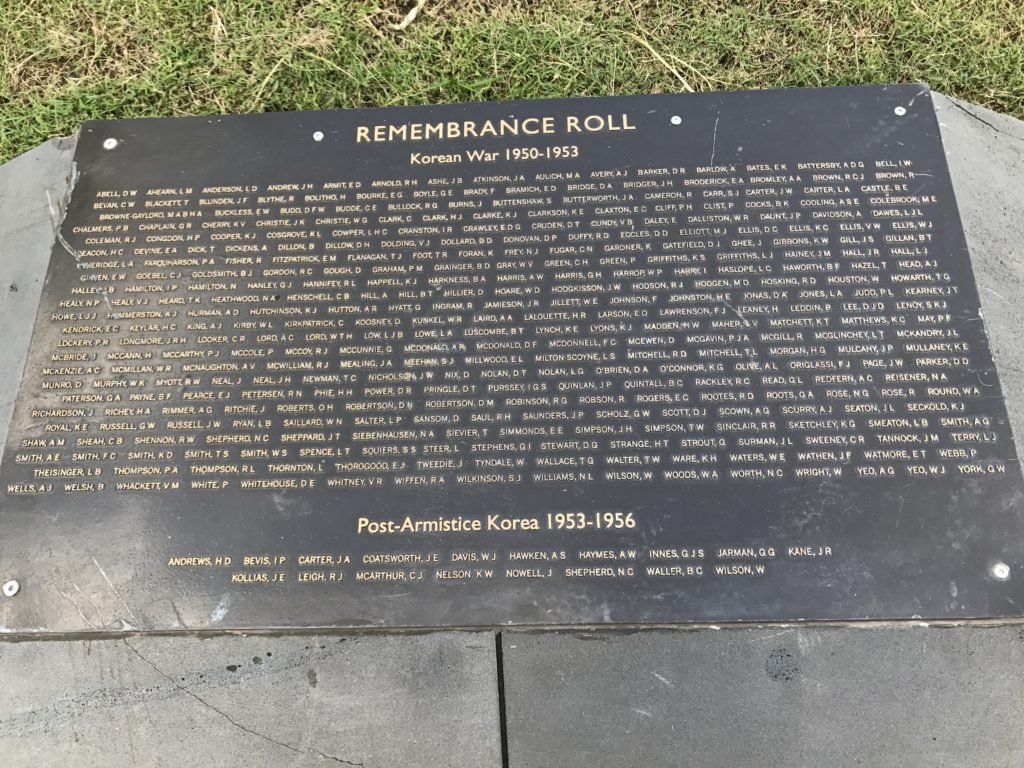

– The count that I have from Puerto Rico was about 63,000. Out of those 63,000, there were 2,700 that were wounded in action. There were about 740 that were killed in action, and out of those 740, there were 122 that were missing. Currently I think there’s about 110 or 112 that are still missing in action. And as they find their bodies or they’re able to identify them, they are added to the Wall of Remembrance in San Juan.

– So, if there’s… I know the 65th earned the congressional gold medal.

– Yes.

– Of course I’m partial, I know they deserved it, but not everybody knows. So, why?

– Okay. The regiment was very successful. They had a maneuver in Vieques called Portrex. They went against the best unit from the United States [——], and they were able to repel that invasion. So that stayed in the mind of Colonel Harris, and when Colonel Harris was in Korea, they asked him that they needed an infantry unit to be able to go to Korea because they were running short. So he said, “Well, I had a regiment I’d like to bring here.” and he mentioned the 65th infantry regiment. But they were… the high brass was very reluctant, because one of the things they said is, “But they never fought during World War I.” Only one battalion fought, which was the 3rd battalion. There were two casualties. And during World War II, they were mainly to secure… or security, of the different bases, of the different places in the Caribbean and in Europe. During the Korean War they were an infantry regiment, and they were well prepared because, like I mentioned before, a lot of them were veterans from World War II. They had experience, they had training necessary to be in battle. And so, that training went on to the new recruits that came in. When they got to Korea, they were instrumental in helping the 1st [—] division exit from the surrounding by the Chinese. Although the Chinese were pushing us back into the sea, the 65th regiment was the last unit to disembark, or to get on the boats, because they were the last ones that were safeguarding the back of all the other soldiers.

– Two last very simple questions. One is, you’re not even a Korean War veteran, why do you care about them so much? Okay? So that’s one. Two, tell the Korean people why they shouldn’t forget.

– When I was in the service, I was serving in Germany, and one of my fellow compatriots mentioned the 65th infantry. I never knew anything about the 65th. I wasn’t interested because I just wanted to serve my two years and leave. When I retired at 60, there was another instance, where I was in Connecticut and I overheard somebody say, “The 65th? They didn’t do anything right.” And that kind of stayed on my mind. I said, “I have to find out about that.” So, when I retired at 60, I said, “I need to go to Puerto Rico, because I want to see Puerto Rico.” [——–], and I did that. But before that, I told my wife and she started crying, and I said, “What’s the problem?” She says, “Well, you’re going to get old on me, and you’re going to die.” And I said… that scared me, and I said, “No, no, no. I have to do something.” So I came to Puerto Rico. Six months I went around the island. This time my brother was calling me. He says, “Look, I need you to help me.” And I said, “Help you what?” He said, “I need you to help me find veterans that were wounded, because I want to start an organization in Puerto Rico called The Purple Heart Organization, to be able to recruit and have a chapter, a register in the national Purple Heart Hall of Honor.” And I said, “Well, I’ll see what I can do.” Meantime, the president of the 65th infantry association was after me telling me the same thing, “Look, I need your help. You’re the youngest, and I need to make sure people don’t forget this organization.”

– So, to the Korean people, why should they not forget the Borinqueneers?

– To the Korean people, first of all I want to thank them very much, because I had the opportunity to go to Korea, and the 65th infantry was very instrumental in safeguarding the country. They were very instrumental in making sure that democracy was installed in Korea. They were very happy to be able to defend your country. A lot of them gave their rights [?], they shed the blood, and they shed the tears. But they did it for a purpose. They wanted you to be happy, your generations in the future to be happy, to be able to live in democracy. And so, the sacrifice that was made by the 65th infantry regiment was not done in vain, your country has progressed quite a bit, your people are very nice, and we really appreciate the way you think about us, the Puerto Ricans and the 65th infantry regiment.

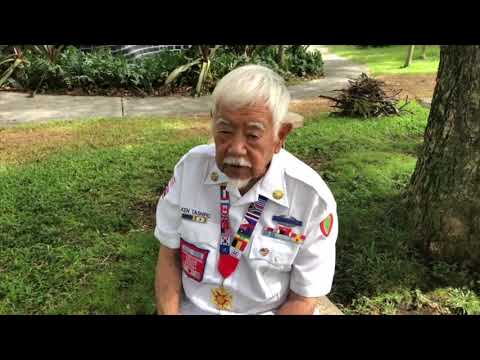

>> Hello, my name is Tommy Tahara, and then I was stationed at Camp [INAUDIBLE] in [INAUDIBLE], Japan, before the Korean War. That was in 1950 when … And then when the Korean War started, I was in the 7th Division, Company E … No, Company F. “Fox Company,” they call it, Fox Company, and then I was stationed in Camp [INAUDIBLE], and then … What do you call it? When the war started, took none of our personnel from our company and put them in the 44 and 25th Division, so we were left. We were [INAUDIBLE] starting [INAUDIBLE] our company. So, actually, we went in August. We went to Camp Fuji, and we were waiting for the KATUSAs to come in. They picked up all the young kids or whoever old men from Korea, and they loaded up them on a ship, and they shipped them to Yokohama, and then they trained them to Camp Fuji. That was in August of 1950, and one of a friend … He’s the old chapter. He’s a KATUSA. His name is Seok, and then he was with the 7th Division. Our 7th Division, we had about 9,000 KATUSAs, and every company had about 100 KATUSAs. In other words, that made us, you know, combat-ready, but we had to train those guys because they came from Korea, and when they hit our cafeteria, our kitchen, they’d get a cup of coffee. They’d put about 10 teaspoonful of sugar in there because, you know, sugar was … They couldn’t get it in Korea, but anyway, they were terrible. They had diarrhea and all that after that, but after we trained them only for about 3 weeks, and then we loaded up on a ship, and we sailed to Korea. We waited in Pusan Harbor, and we waited outside of Pusan Harbor and waited for Operation Chromite. That was invasion of Korea with the 1st Marine Division and the 7th Division, Infantry Regiment. Anyway, I was in the 17th Infantry Regiment, and my friend Seok was in the 31st Infantry Regiment, and okay. We landed in Inchon, and then we headed towards Seoul, but at that time when we left, we were still young. I was only a [INAUDIBLE] 19 years old, and then we saw all the dead bodies all over the train station, civilians and all that. First time we saw those dead bodies, and most of us … Korean civilians over there. They’re … I guess they got killed by the bombing and all the artillery and the ships because we had over 100 ships outside of Inchon. Anyway, after that we went to where the first battle. It was a hill over Seoul, and then that’s the first time I saw bullets flying all over my head, and my buddy right next to me, he got shot right in the throat. He was standing right next to me, and he got shot in the throat, and you know how frightened you get because that’s the first time you see a guy bleeding from the throat now. Anyway after that, we headed towards Suwon and Suwon side, down south. It was the North Koreans were retreating back. It was we were coming back from the Naktong River side. They were coming back up, and we were going down and meeting them, so we had some few battles over there, around [INAUDIBLE] Suwon earlier, and later on, you know, until almost October, they trained … We’re a convoy bound to Pusan, and from Pusan, we loaded up on our LST and then we headed up north on our [INAUDIBLE]. What sea was that? Japan’s sea all the way up north, and then we passed Wonsan and we landed in Iwon. That was in November of 1950, so you see, the 7th Division had three regiments: 17th Infantry Regiment, the 31st Infantry Regiment and the 32nd Infantry Regiment, and I was with 17th. Okay, that’s … I think the 31st one on our left, they closed the Marine side, the 1st Marine Division. They came up from Wonsan, riding down … What it called? San … What it called? Sanjin, or they’re … Anyway, they call that [INAUDIBLE]. I think they call it Hyesanjin. Hyesanjin, that area. Anyway, the Marines were on the left side of the Reservoir. Then couple of battalions of the 31st and 32nd went on the right side of the river, and our friend Seok was in the 31st. He was on the left side, and our 17th, we went up our way through Kaesong. We’re 80 miles above the [INAUDIBLE] to Chosin Reservoir. We ride up to Kaesong and then to Hyesanjin. It was right on the Yalu River over there, and we still [INAUDIBLE] was in the [INAUDIBLE] yeah. Anyway, was in the [INAUDIBLE]. October/November, anyway. That’s the first time I saw snow. The first time I saw snow, I’m from Hawaii, and it was real warm. [INAUDIBLE] just like cotton falling down, you know? So excited. Anyway, we went inside our [INAUDIBLE] first, before [INAUDIBLE] on Yalu River, and then [INAUDIBLE], we found a reindeer [INAUDIBLE] over there, so the guys shot one reindeer, and that was before Thanksgiving now, so they hang up the reindeer, and they cut it all up here, and I think I ate some. I’m not sure [INAUDIBLE]. Anyway, after that, we stayed there in, what do you call, Hyesanjin for a couple of weeks of [INAUDIBLE] in the new [INAUDIBLE], once you’re in [INAUDIBLE]. It was so cold, so anyway, right about that time, the Chinese came down, right through there, or [INAUDIBLE], what [INAUDIBLE] got paid back or something like that, and then the Chinese kept pouring in, so we had to retreat, so what we did was threw the [INAUDIBLE] lot of our equipment. We dropped. We [INAUDIBLE]. Another we had [INAUDIBLE] we couldn’t carry. We could run it, and then we kind of retreated back there. I think, gee, that must have been about over 100 miles to Hamhung, H, A, M, H, U, N, G, Hamhung, and then I think in a couple of weeks, we entered Hamhung, and we set up out base outside of … The 1st Marine was trapped inside here by the Chosin Reservoir, with about two, three regiments of the 7th Division, 31st and 32nd. I think that was called task force [INAUDIBLE]. Anyway, so we were down by Hamhung, and we set up our position over there in the … What do you call it? When the Marines got to the trap over there, they escaped. They came down from Hungnam. Hungnam, it was, Hungnam, and they moved to Hamhung, Hamhung. That’s where they had the big park over there, and we had, oh, so many ships out there, Japanese ships, all kind of ships because we had to escape. We had to get away. Whatever equipment we could carry, and then we load it up on the ship. Was in almost December, almost Christmastime, and the whole division loaded up on a ship, LST or whatever, and then we headed to Pusan. Again, the last outfit that left there was the 3rd Division. They were the last ones there, to blow up all the places that Hungnam, Hungnam, the park over there. And then December, Christmas, almost New Year’s, we were in Pusan, and then we had frostbite. Most of us had frostbite because the cold. Sometimes it was about 30 to 40 below 0, and the wind was terrible. You cannot go outside and just use the toilet over there because it’s so cold, you can’t … You know what I mean. Thirty, 40 below 0, so all our hands all black. You see my hands? Oh, yeah, all black. Anyway, so anyway, we went to Seoul or Pusan. We went to medical. They checked us out, and I guess at that time to last [INAUDIBLE] leave like a South Korean troop, so they got something out. At that time in the ’50s, a [INAUDIBLE] Caucasian, Asian. They’d call us gooks, again, even though I’m an American, but since I’m Asiatic and I look like a South Koreans or whatever, and they looked down on us, some of them, and some of them are nice, but anyway, after that, in January of ’51, we went up north again. [INAUDIBLE] set up position. Maybe [INAUDIBLE]. I know I remember when Chief [INAUDIBLE] someplace in the [INAUDIBLE]. They said Chief [INAUDIBLE] had a gold mine, so everyone [INAUDIBLE] gold mine [INAUDIBLE], and then [INAUDIBLE] went up to [INAUDIBLE], [INAUDIBLE], and then they all went to this, so the reservoir over there, I think it was [INAUDIBLE] or something like that, and then there was a lot of fighting over there, and actually scariest fighting we had was in February of 1951. At night, as a first stand we had a attack from, what do you call, like a bonsai attack where all of [INAUDIBLE] shoot the flares up in the air and the trumpet and the bugle and all that, and they come charging up there. That was the scariest one because you was young and only 19 years old. Anyway, that was the first experience. I said that [INAUDIBLE] because in the dock, you just keep firing. You don’t know who you’re shooting at because [INAUDIBLE], and a lot of troops died here. In fact, the scariest thing is when you shoot in a foxhole, and you wake up in the morning, and your companion is missing because the Chinese coming. You’re in a sleeping bag, sleeping. They grab the sleeping bag and drag you. They drag you, so when you look at, your buddy is gone. It’s very scary, so actually when I came back home, I used to get nightmares. When you’re in bed, you get what they call PTSD. [INAUDIBLE] screaming in bed, and you are yelling. Yeah, I was like that all those years. Anyway, after June or from 1951, they gave me a, what do you call, rotated. They rotated me out because I had enough points, so instead of coming back to Hawaii, I met my friend in Sasebo. Sasebo, and you know what he did? My friend, he went to personnel, and he changed my order, saying that he’s … I’m going to what do you call? I’m going to the East Coast with him, and he gave my name and his address, so they shipped me over to … on a ship, and we went to San Francisco, and the three of us, with friends, took a train all the way to Chicago and, from Chicago, caught another train to Baltimore. Went to Baltimore. In Baltimore, my friend, he had a wealthy family. They had a hotel, like a inn, a restaurant and a barber shop, so my friend’s dad, he bought him a new convertible, Ford convertible, and that was in ’51. Let me see what’s that, July … No, it was in August, September. Two months I was staying with him in Baltimore, called Baltimore. Anyway, we had a lot of fun. Then we separated. He went to Fort Benning, Georgia, and they sent me up to Fort Dix, New Jersey, so I was with the 39th, the 9th Infantry Division, 39th Infantry Regiment. There was a basic-training company, and then, see, I couldn’t stand the New Jersey weather. It was terrible. It was so cold. [INAUDIBLE] Atlantic Ocean, but it was … because I had all frozen hands, fingers. I didn’t like the cold, so I said, “I need a transfer.” So they tell me, “Where you want to go?” They gave me three options: 3S, it was on the great [INAUDIBLE] 3S [INAUDIBLE] same thing or Germany or Japan. When they said Japan, I said, “Oh, okay! Okay, I’ll go back to Japan,” so they sent me back to Japan, but you know where they sent me? They sent me with the first captain, the first captain that [INAUDIBLE] Korea from [INAUDIBLE] to [INAUDIBLE] Okaido. I went with a … They sent me with a 7th, I mean a 1st Cav, 7th Cavalry Regiment in support, outside [INAUDIBLE] Cav [INAUDIBLE] profit, so we had ski training over there, and anyway, I was there for all about, what, 2 months. Then I went AWOL. You know AWOL? And when I came back after about a week, they threw me in the brig, all of us in the brig. Well, they sent us back to Korea! Instead of giving us [INAUDIBLE], they sent us all back to Korea, so I ended up with a 3rd Division, so 3rd Division when I went there was in 2nd Battalion. They send me to 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Division. This guy … They sent me to his headquarters company. It’s like a, what do you call, this Japanese guy, Futo. He was heading a squad of Koreans who could speak Chinese and all kind of Shanghai and Mandarin and all that, and then they could speak Japanese and, of course, Korean, so anyway, a squad of Crown, we call that the King Fishes, so I was put in charge of that. I was a squad leader for that, and it was all Koreans, and they don’t know Japanese. I could speak a little Japanese, so that’s why they put me in there. Anyway, what we did was … Everybody, we had some radio and we’d listen to the, what do you call, the Chinese and the North Koreans, whatever they say on their radio where they communicate, and we intercept them, and we tried to decode what they’re saying. They’re all talking [INAUDIBLE] we call it [INAUDIBLE]. The Chinese are talking code, so they’d translate to me in Japanese, and I’d try to translate it in English to the battalion headquarters. Most of the time, we were up on the hill because when we sent out a patrol at night, that’s when you … We had to listen to see if the enemy is … They came on the patrol that’s coming in, so anyway, sometimes when we’re up on the lookout, way up there and then we’re looking down, and then the Chinese threw artilleries, hundreds of artillery on us. In fact, one time the artillery was so close, it hit our bunker and then blasted us. It was almost a bit, only about 4 feet or 5 feet in front of me. I said the whole bunker, and I had three, four Koreans with me that were translators. All of us in that bunk [INAUDIBLE], and before I knew it, I was on a helicopter. They sent us back because my eardrum was blasted. Couldn’t hear, had concussion, and so they sent me back to the back. I don’t know how far back we went but helicopter. It was the first time I rode in a helicopter, and I was so scared. You know, helicopter is so nice, so small. Those days, the helicopters were small. Anyway, I was there for almost 1 month, and they sent me back to the company, and you know what? To this day, I cannot remember anybody, the first sergeant, the captain in that time. When I came back, I don’t know how I came back, and it took me months and years to find out how I came back, and I had PTSD. Anyway, when I came back in 1953, I’m telling you, oh, I didn’t know what to do because I couldn’t remember a lot of stuff. It was because of that concussion and all that. My doctor said maybe I had something, amnesia. You forget, yeah? And those days you didn’t have this kind of VA and all that. I had to go to a private doctor, and the private doctor … My hands were all blue and cold. They thought I had Raynaud’s disease, so I had to quit smoking, and I had to quit drinking coffee because it affected my hands, so to this day, I don’t drink coffee or smoke. I used to smoke two packs a day, but … Ah, that’s okay. Anyway, after that, when I came home in ’53, I found a job in the Marshall Islands with AEC, Atomic Energy Commission. We were testing those atomic bombs or hydrogen bomb, so we were a service company [INAUDIBLE] and in our, let me see, [INAUDIBLE] November. November, I went back to the Marshall Islands to stay there in Enewetok Atoll. Enewetok Atoll has about 22 small islands, and we were on Parry Island, and then what we did was our company was service [INAUDIBLE] of scientists, the army personnel there. You know, we’d clean. We’d clean their house, laundry, everything. It’s the kind of job we had. Anyway, I stayed there for about a year and a half. Then I came home for a couple months. Then I went back, and I did that for about 6 years until … from end of 1953 to about 1959. Almost 6 years I did that. And after that, when I came back, I worked for the US Post Office, and then at the post office, I was assigned as to deliver mail. At that time, we were delivering mail with a motorcycle, motorcycle with a sidecar. We’d put all the mail in a sidecar and then deliver the mail, so actually after that we had trucks, all different kind of trucks, and during that 44 years I worked as a carrier, I got bit six times by dogs because at first when you ride in a motorcycle, we didn’t have any leash law in Hawaii. Leash law is you’ve got to leash the dogs, but the dogs were always running loose all over the place, and they’d chase the motorcycle and jump on you, and they’d bite you. I got bit six times. Anyway, after that, we had the leash law, so they had to tie down the dog or put them in a fenced house, so they cannot be running around loose, so I was 44 years as a carrier, and then I retired in 2004. Ah, that’s about it.

>> And right now you play such an instrumental role …

>> And then in 1988, I joined our chapter, Chapter One, and then later on, 1988 and about 2006 or 2007, I started helping out with the POW/MIA guys. They used to come every year to what you call a reunion. Every year we had a guy in our [INAUDIBLE] POW [INAUDIBLE] Matsumoto, and he used to handle that, and I used to help him with our [INAUDIBLE]. Anyway, that’s how I learned how to do things, how to make a reunion in order. After I knew how to do that, I had to contact with all the personnel down in Hickam, down in Camp Schmidt, Hickam, and then me …

>> What …

>> Me and another guy, we did all our chapter’s event, even punch bowl event or [INAUDIBLE], whatever event we had in [INAUDIBLE] Christmas or whatever.

>> What does it mean to you, the legacy of Korean War veterans?

>> What’s that?

>> The legacy of Korean War veterans, what is it to you?